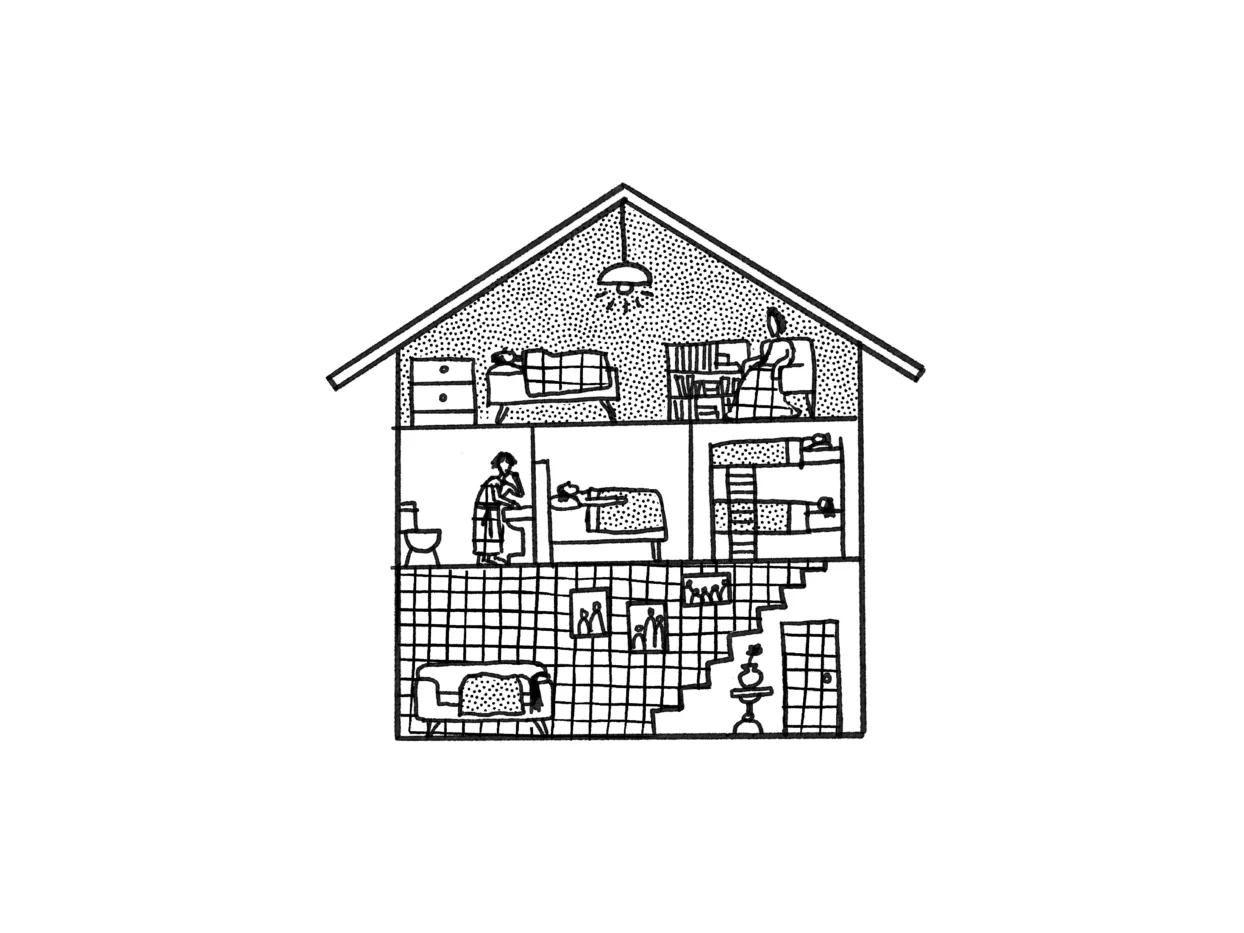

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

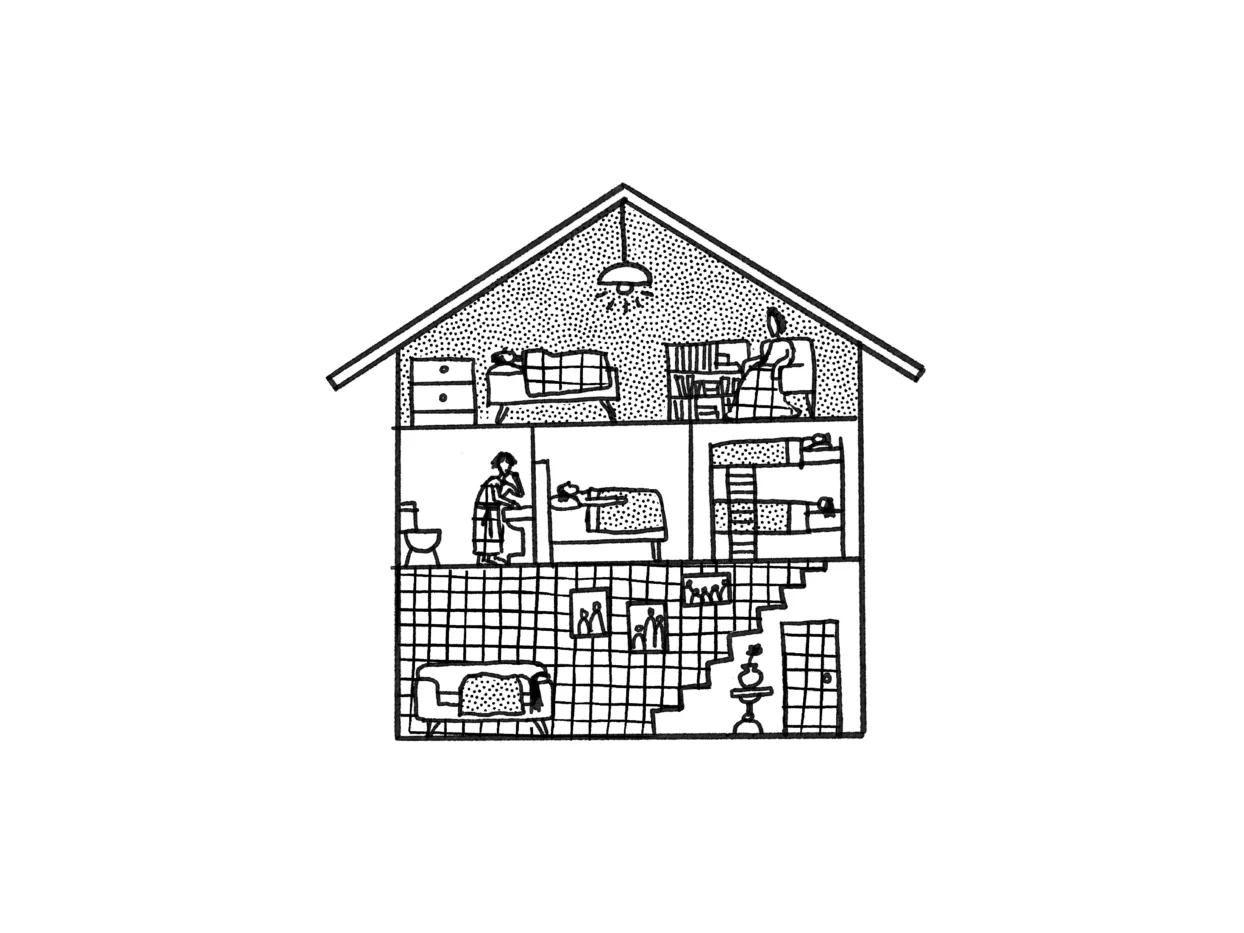

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

I’m the recipient of a blessing that might sound like a curse. I live with my mother — in fact, I live under her, in a house stacked with my grandfather, my boyfriend, and, as of a year ago, my son. My fear that this arrangement would be constraining lifted entirely when he was born: my mother takes care of him for a good part of most workdays and weekend nights. In the mornings, my grandfather watches his great-grandson scuttle around his ankles.

Twenty-eight years ago, my mother made a great effort to avoid this same experience. She and my father relied on the help of family when my sister and I were infants, but they lived in their own apartment. The judgment and gossip of aunties; the cold shoulders of mustachioed uncles; a demanding younger brother; and my grandmother herself, who threw a Bible at my mother when she found out she was dating my father (she got over it soon after): my parents left all this behind, but at some expense, accruing tens of thousands of dollars in credit card debt.

When I moved back in with my mother after college, I worried about regressing psychologically. When I decided to have a baby under her roof, I worried about regressing historically, resurrecting the kind of pre-nuclear household that burdened its women and children with oppression by multiple generations. Now I think this may in fact be the future — that high rents, low incomes, and delayed inheritances will stuff people back into their childhood bedrooms. As home prices rise faster than wages, familial assets come to mean much more than a salary, even a middle-class one. And once we’re home, some parents — and especially mothers like mine — can take upon themselves the load that should be the state’s, providing not only subsidized rent but also food security, the occasional cash transfer, and free childcare, in addition to the free eldercare they often already supply.

I make less than the median college graduate. How many people my age, if they had relatives with stable and capacious housing, would move back home? (Already almost half of Americans between 18 and 29 have.) They might have to sacrifice certain freedoms their peers enjoy: open relationships, security in the knowledge that their mother will not hear them having sex, an entire weekend free of familial responsibilities. A successful arrangement would be contingent on relatives like my mother, who, to the extent any parent can, understands and respects me and my partner. And it’s really only possible for it to feel like a choice, not an obligation, because the house itself is an asset that will eventually pass to the younger generations within it — a property inheritance structure that limits so many other people’s lives. But distributing the labor of eldercare and childcare means less pressure on everyone — the dream, obviously, of a communist utopia.

For two hundred years, people have been fantasizing about lives in which they cook together every day, sleep with the doors open, forget whose children are whose, shed gender, undo race, rear cattle in the evening. These feminist fantasies found new form in the 1960s, theorized for a new age by the second wave and put into practice by hippies and anarchists. At the same time, conservatives, recognizing the welfare state as a form of income redistribution, began to dismantle it and instead tie the fate of families to their ability to secure property. Even for those it benefits, the asset economy means that care is only provided in private. The multi-generational family in a private home — all paying rent toward the same mortgage, recreating the welfare state inside a single domicile — is a much-diminished utopia.

I didn’t expect to have children in my mother’s house, though I certainly also never dreamt of a nuclear unit, which always seemed to me like it would bring a heavy and isolating burden, especially on women. But with my mother around, my baby is never less than a loud, messy joy. I wanted children because I like a crowded dinner table. My vision of an inhospitable future warms with the thought of my son’s friends, my own, my sister’s, my mother’s, putting out cups for water and teaching each other to chop onions. If only it didn’t have to happen at home.

Nawal Arjini is an assistant editor at The New York Review of Books.