1.

Even Netflix thinks it’s time to log off. Last month, the streaming service released The Social Dilemma, a documentary that promised to “unveil the hidden machinations behind everyone’s favorite social media and search platforms.” Intercut between dramatizations featuring actors you’ll sort-of recognize (Pete Campbell from Mad Men, the guy who played Larry’s dermatologist’s son on the most recent season of Curb) are the direct-to-camera testimonies of former tech employees who attempt to lay bare the inbuilt evils of the platforms they helped create. Filled with breathless descriptions of the all-powerful “algorithms,” the film is yet another exposé of perils that have been hiding in plain sight for at least a decade. According to the Times’s review, while “much of this is familiar” and “not a revelation,” the film is still worth watching for its clear takeaway: “the perniciousness of social networking platforms is a feature, not a bug.”

Not long ago, such a conclusion would not have rung quite so familiar. In 2017, Mark Zuckerberg floated a plausible presidential run, invoking JFK to announce the generational imperative to “create a world where everyone has a sense of purpose.” In starting Facebook, he said, “My hope was never to build a company, but to make an impact.” It was the kind of techno-optimism that animated much of the conversation around Silicon Valley and generated the sense that the potential (The Arab Spring! The Hyperloop!) outweighed the risks. When the less-rosy side of the tech revolution was acknowledged, the prescriptions that followed mostly related to our need to “unplug,” undergo a “digital detox,” or, as The Atlantic made briefly fashionable, convert our screens to grayscale.

And then something shifted: the sense of hope surrounding Silicon Valley gave way to techno-pessimism. Liberal boomers took to Facebook en masse to declare that Facebook was responsible for Trump. Each new development was grounds for distress over the state of democracy in an online age—Russian interference! Trolls! Bots! Snake emojis!

Suddenly, the internet was de facto “pernicious.” The phrase “our tech overlords,” such a recent lexical invention that it does not appear in Google Ngram, is now used in every major publication, all but absent any irony. George Soros, a fixture of online conspiracy theories, told the World Economic Forum that the internet is “a web of totalitarian control the likes of which not even Aldous Huxley or George Orwell could have imagined.” Zuckerberg, once a “bona fide tech celebrity” and the “most popular tech CEO,” was called “the Bond villain of our online lives” by The Guardian earlier this year. Over the summer, polls showed a 28 percent drop in Facebook’s favorable ratings since 2016, and GQ wrote that the idea of social media as definitionally “evil,” which had “seemed extreme two and a half years ago, appeared to just now be arriving in the mainstream.”

We’ve reached the point in the discursive cycle where there’s nothing new to say. The result begins to seem like an admission that we already know everything we need to know about how bad the problem is; we’re just testing out different angles on it. Reviews of recent tech books assess how well they peddle a familiar critique — and whether this time, it can possibly get through to readers. Andrew Marantz’s Antisocial is praiseworthy because, a writer in the New York Review of Books explains, “while I knew most of the material… on a rational level, it had gone by and deactivated me, too squalid and depressive to hold in my mind.” Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley is favorably reviewed in the Times as “here to fill out our worst-case scenarios with shrewd insight and literary detail,” confirming that “everything over there is as absurdly wrong as we imagine.” The 704-page doorstopper The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (which made Obama’s reading list) has “given new depth, urgency, and perspective to the arguments long made by privacy advocates,” according to the NYRB.

What happens, though, when new depth, urgency, and perspective still don’t solve the underlying problems? What to do when we seem to have thrown everything in the narrative arsenal at these problems to little avail? Big Tech gets shifted out of the plus column and instead added to the long list of enemies we can’t live without — the forces we malign without accounting for their systemic roots. (Maybe the problem isn’t surveillance capitalism.)

The news-entertainment factory runs on endless repetition of alarm at the symptoms of a widespread decay. Stream the new doc about the ills of the internet and decide it’s evil, rather than interrogating the profit structure that drives its success. Read a millionth article on the latest sign of climate catastrophe, without acknowledging that the destruction of the planet is a predictable side effect of industrialization, globalization, and overproduction. Seethe over a long exposé on Trump’s taxes, as if the evasion of civic responsibility weren’t baked into the global financial system. Check the breaking news on the coronavirus, but don’t reckon with its connections to rapid environmental degradation. Then, close the tab.

In a year that demands near-constant attention to our devices, whether for the professional or the social, calls for consumer-side reforms like parental controls or “reducing our screen time” now seem especially quaint. Amid all the moral panic about tech, it’s barely mentioned that our ability to undertake a world-historical project of social distancing is a direct result of the internet — in prior pandemics, a disruption on this scale was not on the menu of possibilities.

As the consensus has turned firmly against Silicon Valley, we’ve found ourselves in a situation that shoves screens into nearly every aspect of our lives, acting out the dystopian scenarios of which we’ve been warned. The options for redress are limited: keep watching documentaries about the problem? Or… vote?

2.

We’re closing this issue on the eve of an election that simultaneously feels like it has already been happening for four years and may never come. Everyone from Harry and Meghan to Eileen Fisher and Chloë Sevigny agree that this is the election of our lifetimes (again). Larry David is campaigning to flip state legislatures; the estranged hosts of Call Her Daddy are pushing voter registration; Randy Quaid claims to have canceled out Chevy Chase’s vote for Joe Biden. “WE’RE IN A FUCKING STAGMIRE,” @realrayabruzzo wrote on Instagram. “VOTE!!”

Last week, the Times Editorial Board implored us, in an over-produced graphic feature, to “END OUR NATIONAL CRISIS” by voting Donald Trump out of office — the clearest articulation yet of a collective failure to conceive of a timeline beyond November 3rd. It’s nice to believe that there are simple binary answers, and presidential elections are effective stewards of this fiction. The past two decades have trotted out a sequence of increasingly unmissable opportunities to vote. By 2032, scientists estimate that we’re due for the most important election in history.

But the fact is, we do not face one crisis. We face many, and they began long before November 8, 2016. Crises are rarely occasioned on single days or by single people; they’re slow, drawn-out ordeals, formulated in the open-floor-plan offices of corporate giants, the ping-pong rooms of tech behemoths, and the back halls of government. As we’ve more than learned this year, they’re experienced as both terrifying and mundane.

When looking for culprits, it is tempting to lay our grievances at the feet of the media. We’ve done that ourselves. The network news and online feeds will always favor meaningless scoops, sensationalized yarns, and ginned-up pseudo-tips from cozy government sources. Pitched at the highest key, every update has become critical and every story a plausible push notification. It’s difficult to stay alert to an ongoing state of emergency from which there is no clear exit. But at least some of the fixation on the media — New York Times headlines, MSNBC punditry, book deal payouts, and Facebook-sourced “fake news” — masks an undercurrent of frustration with the stagnancy of our politics.

How do you rationalize the red-alert attitude when the most powerful popular appeal you can manage is a banal plea to vote? The activity and sense of political possibility ($1,200 checks! The Superdole!) that marked the beginning of the pandemic have given way to a more familiar sensation from the Trump era: the realization that our economy, our government, and our social ties have been quietly unraveling for a long time, and that few people with power are doing anything real about it.

In our magazine’s opening salvo this summer, we poked fun at the literary media’s self-importance and the mainstream media’s blind spots. We had grown tired of the topics that have been covered beyond their due — Russiagate, for instance, or the early-pandemic experience of some writers in Brooklyn. Now, we’re looking at what’s missed in all the relentless alarmism — the muted tones washed out by the spotlight, the questions drowned out in the noise, the explanations that rely not on movie villains but on long, slow processes. In this issue, we’ve turned our attention to the sinister underbellies of subjects often deemed boring — accounting, Covid data-reporting, the quiet merger of two British government departments — on the premise that institutions break down incrementally, and they’re worth monitoring before the point of collapse.

But this issue is not only about bureaucracy: we’re also focused on the subtleties overlooked in our more dialed-up conversations. To take the long view of this year’s massive disruptions to work and home lives, we speak with the feminist luminary Silvia Federici about care work, universal basic income, the politics of the commons, and more. Digging up an archive of letters by Soviet schoolchildren of the 1970s, we reconsider Angela Davis as a cipher for any number of ideological beliefs. We look to Madagascar, where the government has sold a dubious Covid cure with misleading anticolonial rhetoric. We place the recent James Baldwin revival in the context of anti-racist reading lists and liberal endeavors like the New York Times’s 1619 Project. And we revisit a grand theory of art from the 1960s for insights on our hyper self-conscious world.

As the re-opening debates rage on, we invite students and teachers from Iceland to Kashmir to report from the front lines on the compromises being made to go (gradations of) virtual. We consider the climate threat — its science, as well as its colonial dimensions — through the eyes of a researcher who moonlights as a firefighter in the California blazes.

With the hope that the curtain is falling on our current political farce, we screen a series of schlocky political comedies, and our extremely abbreviated reviews cast a critical glance at everything from arthouse documentaries to roasted watermelon to reptile appreciation groups. Our short story takes us to Nepal; our poetry tours the Reagan Presidential Library, and journeys to the bottom of a very repetitive list.

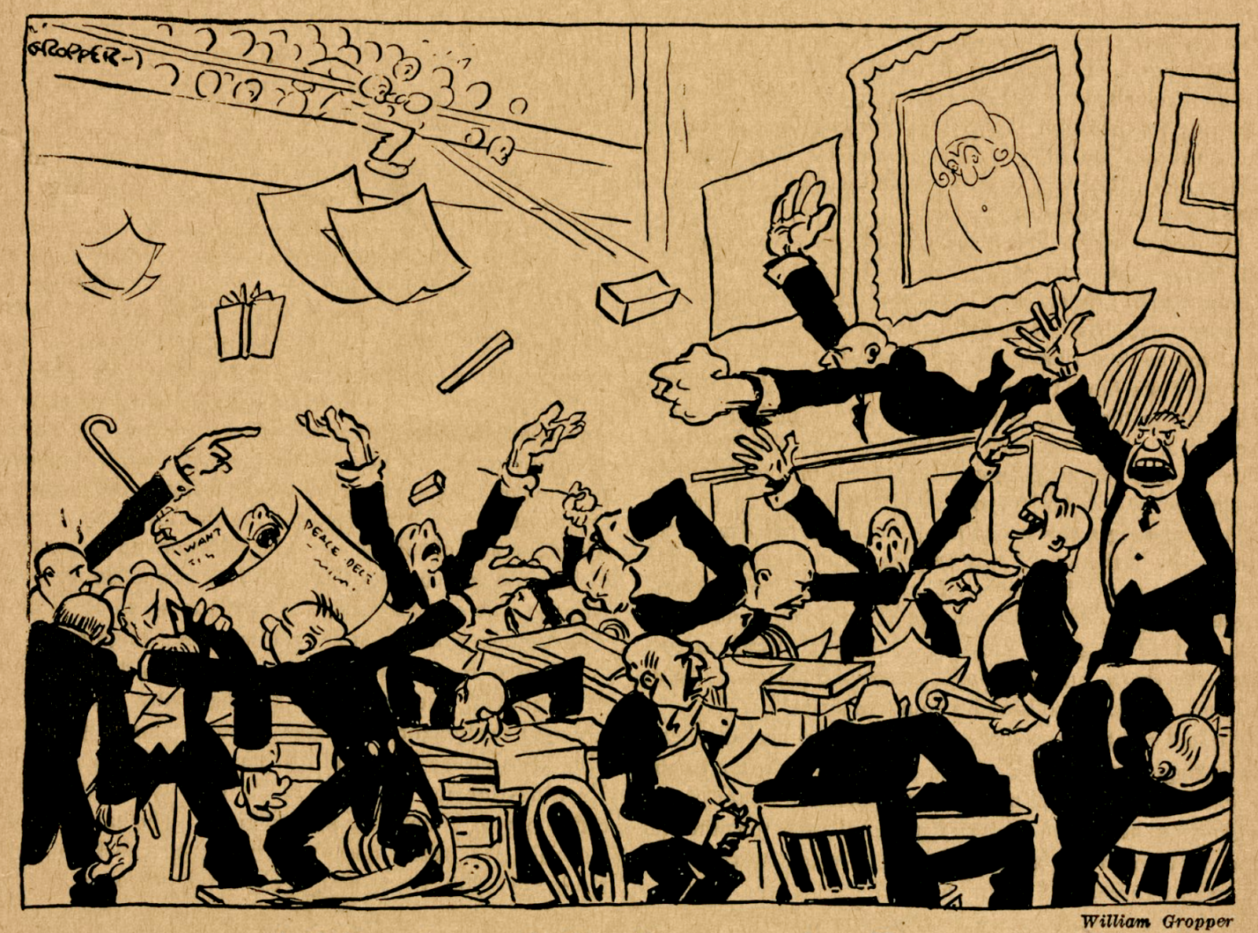

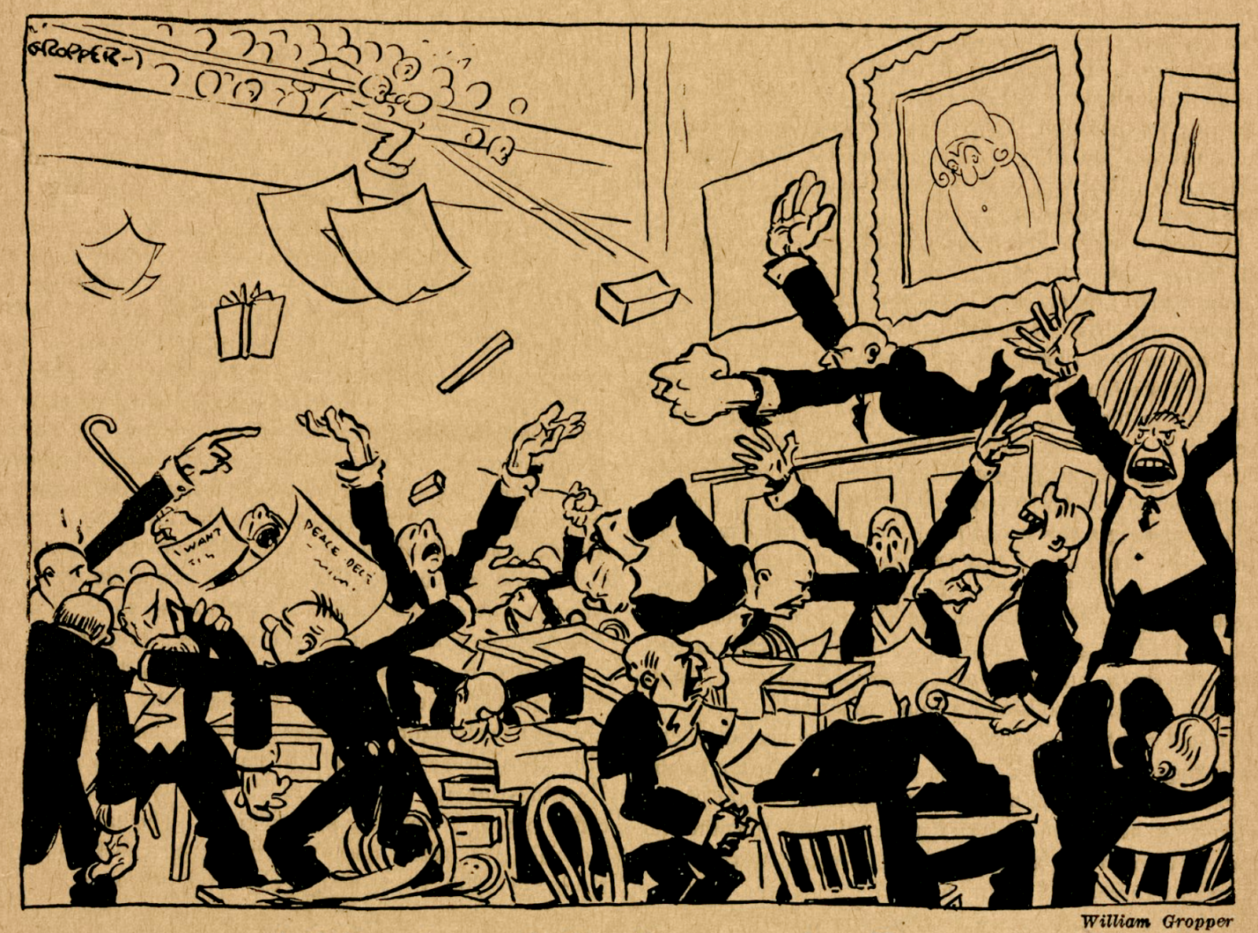

In our first issue, we recalled the modernist monthly The Masses, a magazine whose tone and politics we’re hoping to emulate. After two trials for disseminating “treasonable material” about US intervention in World War I, The Masses was shut down in 1918. Undeterred, the editors regrouped to form a new publication, The Liberator. Our second issue’s cover repurposes an image of Eugene Debs from that magazine’s May 1919 number. At the time, Debs was in prison, facing charges of sedition. He died seven years later, by which time The Liberator was defunct.

It’s been a year of crushing disappointment with the limits of electoral politics — precipitated first by the departure of Debs’s modern political heir from the race, and then by the realization that even the more favorable general election outcome will produce no silver bullets. In the context of 2020, Debs is a reminder that the struggle for a just society is a long one, and that setbacks (postal and electoral) are part and parcel of any worthwhile opposition. “Intelligent discontent is the mainspring of civilization,” Debs said in 1908. “Progress is born of agitation. It is agitation or stagnation.” In a time of Netflix documentaries and up-to-the-minute news updates, stagnation is inseparable from the monotonous drone of the doomsayers; it’s too easy to forget that alarmism isn’t the same as intelligent discontent or agitation. These are what we need now.