Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

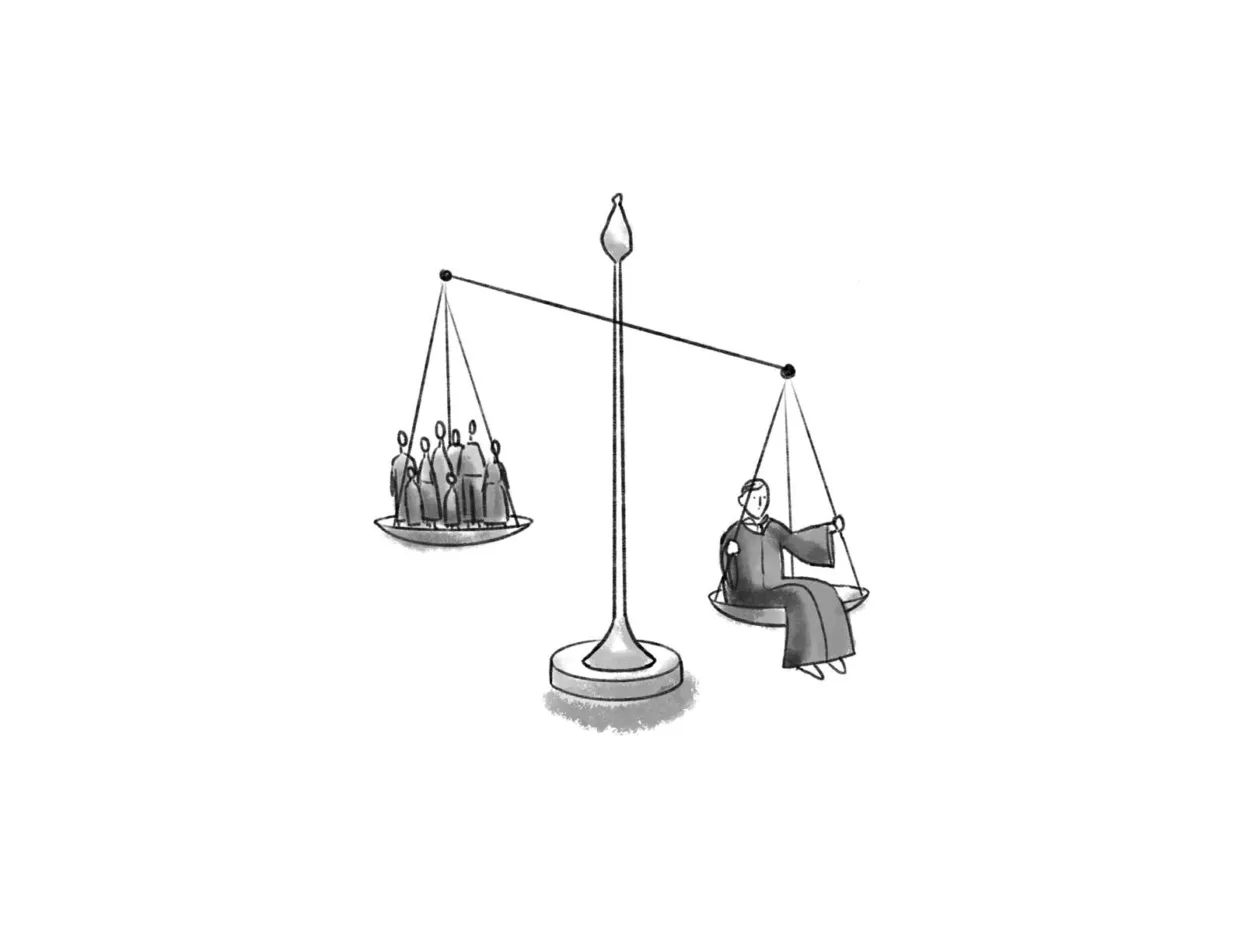

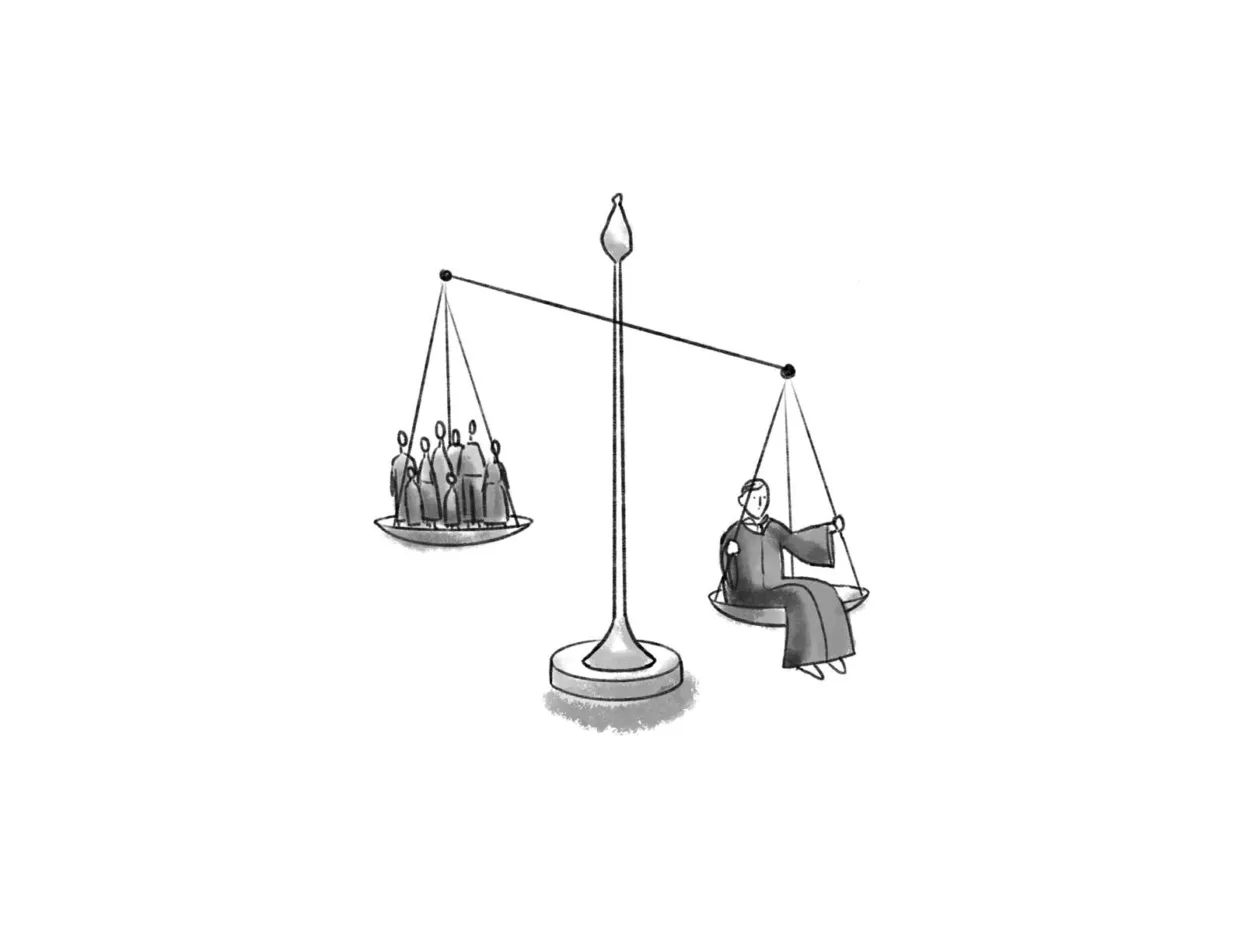

American constitutional politics has a terrible bottleneck problem. Virtually all meaningful debate and reform is funneled into the judiciary. Its dominance is often defended on the grounds that, as law professor and diplomat Eugene Rostow contended in the 1950s, the bench — with the Supreme Court at the top — oversees a “national seminar.” According to this view, the Court, through a reasoned and conscientious engagement with a broad range of perspectives, offers a form of public education. But what judges care about and what moves Americans has always been an uncomfortable fit. At a time when the country is wracked by profound racial injustice, with extreme disparities in health, housing, education, employment, and incarceration, none of these issues are likely to face meaningful constitutional inquiry. They are not of interest to conservative legal activists, so cases around them won’t be heard or debated at the Supreme Court.

The vagaries of the Electoral College and the extreme overrepresentation of rural and white communities in the Senate have made Supreme Court nominations a profoundly undemocratic process. With a vise grip over this process, the Republican Party backed appointees who promote deeply conservative political, cultural, and socioeconomic views. Those justices have the power to determine what counts as a topic worth discussing, in part through the Court’s ability to select its own cases. The result is an almost hermetically sealed box, in which conservative legal activists work out their internal disagreements.

Nearly two thirds of Americans may support Roe v. Wade, for instance, but the Court will take as given that the case was wrongly decided, and then debate how comprehensively states can limit reproductive rights. Mass shootings may be transforming schools into dystopian settings, but the Court will discuss how absolute individual gun rights should be, following the lead of the NRA and gun activists. These advocates influence which arguments the Court takes seriously, as they did with New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, in 2022, when the justices struck down a New York state law limiting concealed carry permits. And while about 70 percent of Americans support same-sex marriage, what’s on the Court’s mind is whether a white Christian majority feels threatened. In a recent case, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, right-wing justices were so worried about how an anti-discrimination law might infringe on the religious beliefs of a Christian wedding website designer that they essentially ignored the fact that the supposed request from an LGBTQ+ client, on which the case was based, may have been faked.

Tweaks to legal doctrine, or the appointment of a centrist or even left-liberal justice, will not save the country from the institutional dominance of the right or unjam our constitutional system. Americans have to reclaim authority over their basic legal and political discourse. And this means displacing the Court as the center of our constitutional conversation, by reducing the authority of the bench and by strengthening avenues of popular lawmaking.

Unlike other countries, the United States has no functional amendment process that would allow constitutional conversations to be pursued outside the courts, through mass movements or national referenda. Elsewhere, systems further limit the power of their judges through larger constitutional courts, term limits, ethics oversight, requirements that certain judicial decisions be reached by a supermajority, and even legislative overrides of court rulings. We should also pursue electoral reforms to defuse the most anti-democratic effects of the constitutional structure. These include reforming campaign finance, expanding voting rights, ending the Senate filibuster, eliminating the Electoral College, adding Washington, D.C. as a state, combatting gerrymandering and partisan election interference, and implementing multimember House districts to counterbalance the unrepresentative winner-takes-all format of Senate elections.

While none of these reforms on their own are particularly radical, their success requires a collective commitment to systemic change across American institutions. It also requires rejecting the long-standing deification of the Court and the individual justices. To make these changes real — and to reclaim the constitution from the Court — will necessitate nothing less than large-scale movement-building and mass political action. But however obstacle-ridden and potentially unruly this path may be, it is the only route for reshaping who owns the Constitution and for truly broadening what horizons our institutions allow us to imagine.

Aziz Rana, a professor of law at Boston College, is the author of The Two Faces of American Freedom and the forthcoming The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document That Fails Them.