Yayoi Kusama with Narcissus Garden (1966) installed at the 33rd Venice Biennale, Italy, 1966. © YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama with Narcissus Garden (1966) installed at the 33rd Venice Biennale, Italy, 1966. © YAYOI KUSAMA

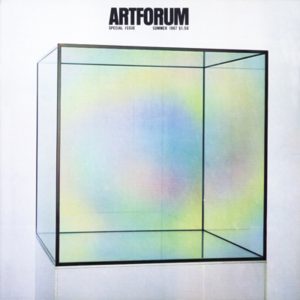

In 1967, a budding art critic and PhD student named Michael Fried published the essay in Artforum that would make him famous. “Art and Objecthood” was on the surface a piece that took aim at the Minimalists, then a group of up-and-coming artists led by Donald Judd. But embedded in the critique was a fully-fledged theory of art — in many ways the last of its kind. In the years since, as art began to seem too multiform for grand statements about its nature, sweeping theories have gone almost entirely out of fashion. Yet Fried’s essay is still taught in virtually every college-level aesthetics and postwar art history course. It has been called “the most influential and widely read piece of art criticism of his generation,” and he has gone on to make numerous other contributions to art history and scholarship over the course of a lengthy career. I count myself lucky to have gotten to know Fried through his work; four years ago, I published a book of his poetry, and next year will publish a selection from Baudelaire’s Salon of 1846 with a new introduction by Fried.

Earlier this year, I decided to revisit his early broadside against Minimalism just as MoMA opened a major retrospective of Judd’s work, following years of growing cultural attention to Minimalist art and its ubiquitous stepchild, lower-case minimalist design. What I found was an argument narrowly focused on a select group of artists, one that relies on the exclusion of some of the most important and enduring work of the 1960s. Reading the piece today, it’s difficult to understand how “Art and Objecthood,” which presents a theory so complete and convincing — and still so widely read — could have been so out of sync with the art of Fried’s time, and of our own.

Minimalist artists — including those, like Judd, who rejected the label — pioneered the use of everyday materials like fabricated metal and plastic to create simple objects. Judd’s plexiglass and metal “sculptures” sometimes hung on walls; they often resembled containers or shelving, and recalled the aesthetics of industrial design. Instead of providing a reprieve from reality through a fictional space created by a canvas, Judd’s sculptures were intended to reflect the world as it actually was.

In “Art and Objecthood,” Fried argues that art should provide transporting experiences rather than what he saw as more pedestrian ones offered by Minimalists through their objects. In Romantic terms, Fried idealized art that lifts us out of everyday life, versus art that reminds us of the world in all its non-spiritual dimensions. For Fried, certain abstract Modernist painters and sculptors enthrall and captivate, while the Minimalists do the opposite — their work is too rooted in the world to move us anywhere at all.

What does it mean for a theory of art to be wrong or right? There is no hard evidence that proves the predictions or positions of an aesthetic theory to be true. Such theories advance arguments that are both philosophical (addressing what we see and how we judge what we see) and critical (judging the relative significance of artworks over and against one another). A much earlier philosopher-critic, the German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, captured the tension between these two demands in his famous critique of the Laocoön, an Ancient Greek sculpture of a man and his sons being strangled by serpents. Lessing argued that the expression of pain on the father’s face is not intense enough to match the brutality of the scene, and from this isolated critical judgment he extrapolates a theory about the Ancient Greeks’ idea of formal beauty: nothing, not even the horror of serpents killing Laocoön and his family, could justify the depiction of a grimace that would mar the beauty of a balanced face. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Fried wrote squarely in this intellectual tradition — part of why his work has such staying power. Like Lessing, he is concerned with both philosophy (foundations and arguments) and criticism (seeing, feeling, and explaining one’s preferences). Fried pointed to a small, now relatively obscure group of modernist painters as emblematic of what he thought art should be, and he used this preference to develop a general theory of the ways in which Minimalism (and the cultural shifts it represented) fell short.

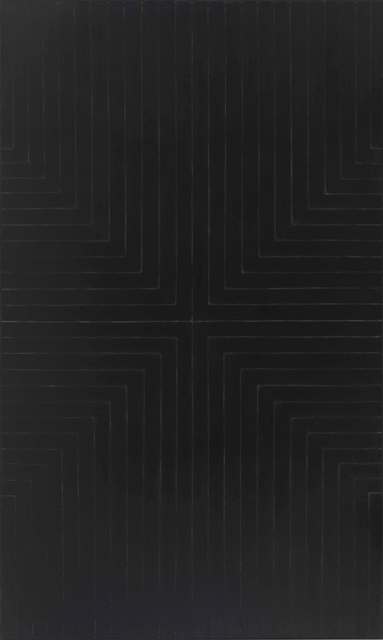

Fried met the abstract painter Frank Stella when both were undergraduates at Princeton, and Stella would play a significant role in shaping how Fried looked at art. By 1966, when Fried curated a show at the Fogg Museum called “Three American Painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Frank Stella,” he knew all three artists. More than an attempt to advance the careers of his friends, the show functioned as a statement of Fried’s position on contemporary art. Instead of embracing the new movements that were already well underway — from Judd’s Minimalism to Warhol’s Pop — Fried instead looked to abstract artists who still believed in the modernist ideals of pure expression and pure experience, rejecting anything extraneous to the artwork.

By the time he was a graduate student at Harvard, Fried had also gotten to know Clement Greenberg, the preeminent critic and champion of American abstraction — and of modernist art as a whole. From Greenberg, he had learned the language of modernist criticism, a no-holds-barred belief in the power of abstraction to represent avant-garde ideals. Greenberg and Fried were both invested in a hierarchical view of art — the idea that certain artworks and artists pushed culture in the right direction, while others were retrograde or lowbrow. Greenberg had championed Pollock, who died in 1956; Fried favored his artistic descendants: Stella, Olitski, Noland, and the sculptor Anthony Caro, whose control of color, shape, and composition Fried considered an advancement in the history of art.

Fried also attended courses in philosophy with Stanley Cavell, who constructed a theory of modernism which was structured around truth and fraudulence. For Cavell, the question every piece of modern art posed was: Is this authentic, or am I being duped? It’s a version of the “my child could do that” response to contemporary art, and it’s a feeling anyone who has looked at art made in the past century has had to confront. And the further we have moved away from the narrow expertise in painting and sculpture that characterized art for thousands of years, the more pressing the categories of authenticity and fraudulence have become.

From Cavell, Fried learned that the very first question that the art of our time puts to us is whether or not we should take it seriously. In “Art and Objecthood,” Fried reformulated that question, and he answered it categorically: the good, serious art is in the modernist tradition, while Minimalism takes us away from the world of the spirit and down a dangerous road of hyper-self-consciousness. A half-century later, it’s clear that the tensions Fried identified — between what is true and good and what is fraudulent and bad — still plague the art world, but while the Olitskis and Nolands are hardly part of the contemporary conversation, Judd gets a retrospective at MoMA, and minimalism has not only reshaped the spaces in which all art is encountered today, but also made its way to the center of culture through design. The work Fried disparaged, in fact, turned out to be the art that has most influenced the world we live in now.

Fried’s essential argument about the abstract artists he favored was that their work was “absorptive” — that it drew you in and lifted you out of the everyday world. In its presence, you could escape yourself and find moments of “grace.”

The Minimalists — whom Fried called literalists — wanted to define their work against or outside the modernist tradition of painting and sculpture. Judd made his ambitions explicit: he wanted a new kind of art that existed beyond inherited categories. His serialized forms, mostly geometric and made of metal and plastic and wood, did not look like the sculptures of Anthony Caro, which are more composed, less industrial, and less unified. Judd took certain abstract painters’s innovations, like Frank Stella’s early squares within squares, and instantiated them, creating objects in the world that resembled those simplified forms in paint. It’s as if the picture plane of a piece of geometric abstraction had been superimposed on reality: “Actual space,” Judd writes, “is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on flat surface.”

This new avant-garde art — the opposite of the purely “absorptive” work Fried liked — was, Fried claimed, highly self-conscious. “Theater,” or, as he also called it, “theatricality,” was the self-conscious state of mind that stood against “absorption.” A large stack of metal and plexiglass by Judd made the viewer aware, especially in the 1960s, of the existing modernist categories it was defying; of the context or setting — a gallery or museum — in which you were encountering these more mundane materials, and of the fact that it was important to their meaning; and, finally, of the intention that you not disappear into the work but be made aware of yourself standing in front of an object that you had to make sense of. Your mind was incited to activity, thought, and self-reflection, not quieted into blissful transcendence.

Though he cites Judd throughout the essay, Fried’s critique relies heavily on a poignant description by the artist Tony Smith, who realizes that his experience of an almost sci-fi landscape on a drive along the still-unfinished New Jersey Turnpike — dimly lit and under construction — was unavailable in traditional art; it couldn’t be “framed.” But it was nonetheless intensely powerful (“specific” as Judd puts it), the kind of experience he thought art should create for us. Fried took umbrage: “In comparison with the unmarked, unlit, all but unstructured turnpike — more precisely, with the turnpike as experienced from within the car, traveling on it,” he writes, “— art appears to have struck Smith as almost absurdly small.”

If artworks don’t defend their realm, Fried warned, all kinds of experiences might challenge or even replace art experiences, which are often harder to access than a sunset, or an acid trip, or an eerie nighttime drive. “Art degenerates as it approaches the condition of theater,” he writes. “Theater is the common denominator that binds together a large and seemingly disparate variety of activities.” Theater, or self-awareness, was for Fried the way the world weakened art by making all experiences equal, differentiated only by intensity and not by category.

Thirteen years after “Art and Objecthood,” Fried published Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and the Beholder in the Age of Diderot, a book about the quiet power of certain paintings in 18th-century France. Diderot and the French painters from 1750-1780 were most interested in the relationship between the viewer and the painting. Fried tells us that Diderot “used the term le théatral, the theatrical, implying consciousness of being beheld, as synonymous with falseness.” In order to be true, the subjects in a painting had to be present in their world, ignorant of the beholder, so that they could model for the viewer total immersion or presentness — a feeling that was of great significance to Diderot, and of course to Fried. “If you lose your feeling,” Diderot writes, “for the difference between the man who presents himself in society and the man engaged in an action, between the man who is alone and the man who is looked at, throw your brushes in the fire.” There is no point in making art in the first place if you don’t recognize the difference between affectation and action.

Behind the exigencies of any specific artwork lies the bedrock of Diderot’s worldview, one which influenced Fried considerably: that absorption is simple, graceful, and true, while affectation or self-consciousness is ugly, pedestrian, and false. Art should model a better sensibility or mode of being than the one widely accepted as the norm.

Turning back to “Art and Objecthood,” it’s easier to understand the deeper philosophical position Fried tucks away in his debate about modernism and Minimalism: that “theater and theatricality are at war today, not simply with modernist painting (or modernist painting and sculpture), but with art as such.” By this logic, the very attitude that the Minimalists stood for was fundamentally anti-art; it did not privilege the kind of value system or hierarchy of human experience that Fried believed art ought to embody.

This is a moral position as much as an explicitly aesthetic one; these feelings are motivated by Fried’s belief about art’s essential role in modern life. Today, individual preferences in art are presented without much consideration of the underlying value system they may represent or connect to. But art has always been tasked with using visual language to transmit beliefs, feelings, and meaning of different kinds.

Fried found in the artists he loved a particular belief he could get behind — namely, that an art object ought to provide a portal for “presentness.” Work that produces this effect when we stand before it is absorptive, and therefore good in both the aesthetic and moral sense. A piece of art that makes us more self-conscious in some way is theatrical and therefore bad (once again, in both senses).

It’s hard to disagree with Fried’s underlying framework: that in our hyper self-conscious world, presentness is a rare and special gift, one that art can give. Nevertheless, it should be possible to accept presentness as an aesthetic and moral good without adopting a dichotomy between absorptive and theatrical art — or excluding other approaches to artmaking.

For the Minimalists, and even more so for artists today, the real world provides rich material for artistic expression. While it may be true that certain experiences are more self-conscious or “theatrical” than others, the idea that art necessarily degenerates as it approaches this state seems, in today’s art world, absurd. And despite Fried’s best efforts, Judd and his simplified objects soon supplanted the artists that Fried championed, foreshadowing the trajectory of visual art: toward a world of truly mixed-up meaning, where all sorts of objects exist alongside one another, and where people and their differing and shared subjective positions feature prominently in the art experience. The strict formal qualities that excited Fried are simply much less important as metrics for aesthetic judgment today than a newer, less easily defined characteristic — what we might want to call an artist’s conviction, her commitment to a particular vision.

This newer metric, and the art that embodies it, already existed at the time “Art and Objecthood” was published. Fried missed the boat in 1967 in large part because he excluded some of the most important artists of his time from serious consideration. While he was spending time with the heirs of Abstract Expressionism and dismissing new developments in art, others were building the movements that anticipated today’s art world.

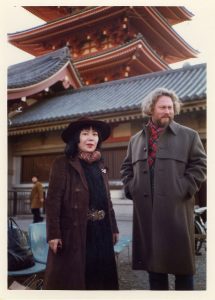

For example, in 1966, while Fried was beginning to formulate the piece he would publish a year later, the artist Yayoi Kusama was showing a new body of work at the Venice Biennale. Today, Kusama, someone I’ve worked with professionally, is one of the world’s most popular and recognizable artists, but at the time she was not well known. She wasn’t an invited exhibitor at the Biennale; she had staked out a spot outside of the entrance for a guerrilla installation. Despite showing regularly in New York, none of the establishment critics wrote about her work, and four years after her presentation in Venice she would temporarily return to Japan.

Fried would have discounted Kusama’s work as non-art, but having widened the aperture for what is acceptable as good art, we have forced our moral considerations into murkier territory, where it’s harder than ever to establish solid ground for any kind of judgment about art or common experience. How can we square this with the intuition — which Fried highlights — that some art is authentic, significant, dense, and true to feeling, while other art is thin, devoid of meaning or import or both? And if Kusama is the former — full and real — then what did Fried miss?

Kusama was broke in the 1960s and sleeping on a door (the relevant chapter of her autobiography is titled “A Living Hell in New York”), but she threw herself into her work. She understood that it would be hard to break through the dominant strain of action painting which was still the rage, and she was disappointed when the Whitney and other institutions rejected her pieces for exhibitions. But she understood that her works “were the polar opposite [of action painting] in terms of intention.” And still, she “believed that producing the unique art that came from within myself was the most important thing I could do to build my life as an artist.”

From the start, she was vocal about making work that spoke to her own neuroses, her own traumas, her own obsessions. She was fixated on the idea of infinity, and of reproducing it from her single perspective, so she started producing net and later polka-dot paintings that create fields of infinitely expanding points; she had an important childhood episode with a pumpkin which led to an obsession with the form; she was afraid of sex because of her tumultuous upbringing, and processed that fear through phallic sculptures, objects covered in woven penis-like protrusions; she wanted to promote open and unashamed love, hence one of her first environmental Infinity Mirror Rooms, Kusama’s Peep Show (or Endless Love Show) in 1966, and her later protests and naked happenings, all of which promoted free love and forced her to confront her hang-ups around sex.

The “I” for Kusama is the site of perception and creativity, but also a kind of prison to run away from — whether by obscuring her world with repeated forms or transporting herself out of reality through her work. The boundaries between her and the spaces she creates become intentionally blurred, in opposition to fixity of all kinds. In her autobiography she writes: “by covering my entire body with polka-dots and then covering the background with polka dots as well, I find self-obliteration. Or I stick polka dots all over a horse standing before a polka-dot background…and the mass that is the ‘horse’ is absorbed into something timeless.”

Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms, perhaps her best-known works today, are — to use Fried’s term — highly theatrical. They are enclosed spaces in which the floors, ceilings, and walls are made of mirrors. Depending on the specific piece, lights either hang from the ceiling or rest on the floor, creating the sense once you enter that you are in an infinitely deep and long room, with light punctuating the space forever, not unlike the universe or deep space. Whether or not you decide to take a selfie, you will inevitably encounter yourself in the mirrored room — that’s the point. You are thrown into an infinite environment that provokes a sense of your own finitude, or maybe of the vastness of what is in you, captured in the expanding space of reflection around you. It is a self-conscious experience.

But anyone who has ever been in one knows that Infinity Mirror Rooms are also highly absorbing (even if Fried would disagree). They transport you out of your literal environment, both by moving you into a new space and by affecting you psychologically, pulling you into their fictive expanse. In Kusama’s rooms, though you may not be captivated by a painting on a wall, lifted out of your world into its transporting canvas, you do temporarily escape into another reality — even if you bring yourself along.

Fried’s categories don’t apply, here, because they both apply: the work is completely theatrical and also totally absorbing, cleaving quite close to the definitions he uses for both concepts. But perhaps more importantly, Kusama creates stillness in self-consciousness, a kind of reflective theatricality that wants to redeem itself.

Kusama represents the realization of an art and a worldview organized around authenticity to self and interiority. But more than that, Kusama represents the possibility that there is a fully-fledged value system, a rich morality, within this new world, totally independent of the more restrictive categories that have dominated aesthetic debates until very recently.

Kusama’s conviction is undeniable. Hers is the highly unlikely story of a Japanese woman, destined for an arranged marriage, who not only shakes off the shackles her conservative culture would impose on her, but also, by listening to herself, manages to turn her inner voice into a universal self; through her form of self-obliteration, she has made room for everyone to participate in this larger inner life. One way to take any idea seriously is to explore it repeatedly, mine it for meaning — whether through objects, experiences, or perception. Kusama is an example of this approach in art, someone who has repeated herself “obsessively,” to use Judd’s word, pushing objects to reveal meaning or intensity until they begin to communicate her worldview as a whole.

One caveat with this kind of obsessive interiority is that the centrality of the self, in either the production of art or its reception, makes it hard to judge what you’re looking at. Formal qualities, like the ones that supposedly stimulate absorption, are easier to control and assess than an artist’s conviction, for example. And in our highly theatrical world, who is to say that someone else’s personal experience — their art, or the way they interpret someone else’s art — is wrong or bad or stupid?

Nonetheless, despite what we might want to call the absolute relativism in art today — all opinions equally valid — we still seem to share deeply held beliefs that some things are better, more valuable, and more significant than others. And we also seem to intuit that these judgments are not simply matters of personal preference, but positions that hold more widely for others as well.

Over the course of “Art and Objecthood,” Fried uses the word “conviction” thirteen times. “Roughly, the success or failure of a given painting has come to depend on its ability to hold or stamp itself out or compel conviction as shape,” he writes. A little later, regarding the artists he loves: “The rightness or relevance of one’s conviction about specific modernist works, a conviction that begins and ends in one’s experience of the work itself, is always open to question.” Here it’s clear enough what he means: modernist art’s power comes, at least in part, from the conviction it compels, which is something we must constantly question.

Though he doesn’t identify it as a central concern, conviction is a crucial term in Fried’s analysis because it addresses deeper truths about an artist’s commitment to an ideal or idea. Conviction, even as Fried uses it, reveals a third path (separate from absorption and theatricality) in which schools and styles are less important than they seemed to be. It is the underlying spirit of a thing that matters, our conviction in it, and the conviction it radiates out. Abstract, figurative, pop, minimal, Op, and so on: every category can shine with conviction if the artist has it. And if artists represent a certain kind of human freedom and fulfillment — and like Fried, I believe they do — then why wouldn’t we hold them to the highest standard? Why wouldn’t we demand conviction from them? As Cavell says, “The task of the modern artist…is to find something he can be sincere and serious in; something he can mean. And he may not at all.”

Conviction is our era’s updated response to the “true” and “fraudulent,” “authentic” and “sincere,” “theatrical” and “absorbed,” debate. Conviction’s roots are in Cavell and other twentieth century philosophers, like Charles Taylor, but they are also in Fried himself — though perhaps not in the ways he had intended.

Conviction is what the best contemporary art communicates — Kusama’s conviction in her own personal narrative, one of suffering, struggle, and neurosis, helped her create a visual language that was her own. Or Judd’s convictions about form and color in real space, which in turn shaped not only the course of art but also the design of the spaces in which art gets shown today, and so many of the objects that surround us in life. And always a sense that the artist could not do it any other way, that she is compelled by an unshakeable conviction in what guides her.

There are so many people making art today, so many more than there were in Fried’s time, that conviction can serve as a kind of guiding light for viewers. Conviction alone is probably not enough; an understanding of art history and a talent for making visual material are common among great artists, but visual talent is highly subjective, largely a matter of personal taste. Grand theories of art may be passé, but if we want new criteria for judging art, we may want to think about what seriousness or commitment or conviction feels like; because once we have a common sensibility, what follows, regardless of visual style, will move us away from the pit of relativism, toward a worldview we can share regardless of our different positions in it. Without that deep shared context of feeling, we will not be able to communicate ourselves effectively. It’s hard to imagine a worthier goal for art right now than communication of this sort.

Presentness and stillness, the feeling of being utterly captivated and overwhelmed by an object, haven’t disappeared from the world because of all these artists and the proliferation of audiences for art, nor are they the only metrics by which we can judge the success of an artwork. Every era has to ask itself what it wants and needs from art, what art should feel like. “Art and Objecthood” ends with a particularly beautiful line to this effect: “We are literalists all or most of our lives. Presentness is grace.” In our self-conscious world, one in which screens are ubiquitous and presentness fleeting, but in which visual art is increasingly tasked with making meaning for us, maybe conviction is a form of grace.

Lucas Zwirner is a writer, translator, and publisher.