Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

Mark Ridley-Thomas had a plan. He also had an accomplice: University of Southern California dean Marilyn Flynn. The problem was that the plan was no good — totally baffling, in fact, like a Coen brothers plot rejected for implausibility. Its central character seemed too bumbling, too ready to risk it all, to be believable for a man of Ridley-Thomas’s position: a giant of Los Angeles politics, then representing two million of the county’s residents from his perch on the board of supervisors, who had earned a doctorate in “social ethics” from USC years earlier.

Nevertheless, this was the scheme. Mark’s son, a California State Assemblyman named Sebastian, would enroll as a master’s candidate at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, which Flynn ran. In exchange, Mark would ensure that USC won a series of lucrative county contracts, allowing Flynn to prop up the financially ailing social work school. When Mark and Sebastian discovered that sexual harassment allegations threatened to derail the son’s political career — well, why not hand him a professorship? Sebastian’s problems were numerous; besides the allegations, cashflow issues and a mountain of debt threatened. Father and son alike hoped he would find safe harbor at USC. And find it he did thanks to Flynn, who secured for him a title formerly bestowed on the likes of David Petraeus and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Did they know this sort of quid pro quo arrangement was totally illegal? The “winking face” and “shushing face” emojis Mark employed in emails to his partner in crime certainly compel one to wonder.

All of this transpired in 2017 and 2018, but it burst back into view in October of 2021 when federal charges against Ridley-Thomas père were unsealed, leading the other members of the Los Angeles City Council to suspend their colleague — for Mark was by then a council member, a position he had also held before his stint on the board of supervisors. Over the month that followed, new scandals reared their heads, and USC, locked in a Sisyphean game of Whac-A-Mole, tried its best to beat them back. It all felt eerily like a retread of three years earlier, when a series of incendiary revelations, including the initial news of the Ridley-Thomas corruption, had rocked the university to its core (more on that later). The Ridley-Thomas case contained many of the ingredients of USC’s scandals of yore: sexual misconduct, large amounts of money being tossed around, and parents committing crimes in order to bolster the standing of their children. The main difference was that an administrator had reported the impropriety — a rare moment of transparency for the university, which has otherwise responded to hints of the rot within by engaging in a series of spirited cover-up campaigns.

At the same time, USC has been the subject of a bitter fight between L.A. City Council Districts 8 and 9, which have both sought to represent the university during the city’s recent rezoning process. Amidst the fresh helping of infamy engendered by these other controversies, this dispute barely registered. An October 20 Los Angeles Times article noted the timeline synchronicity with the Ridley-Thomas debacle, but implied passivity on the university’s part: “USC has been drawn into a second political skirmish at City Hall” (emphasis mine). But the redistricting dilemma should be understood as its own scandal: years of encroachment by the university into its surrounding areas has left residents desperate for the minimal benefits and agency that jurisdiction can provide.

It’s no coincidence that the neighborhoods in question are historically black, and that they have suffered from decades of neglect, disinvestment, and law enforcement occupation. Unlike USC’s highly publicized instances of administrative misconduct, its incursion into the local community is not particular to the scandal-prone school — this kind of parasitism is common among prestigious American universities. USC’s relationship to South L.A. closely resembles Columbia’s to Harlem, where the university, which already owns more properties in New York than any entity beside the city itself, is in the midst of a $6.3 billion expansion into the Manhattanville neighborhood. Or Yale’s to New Haven: in a 2019 address entitled “New Haven and Yale: Three Centuries of Partnership,” Yale President Peter Salovey listed the Ivy’s various charitable commitments to its city. New Haven currently faces a $66 million hole in its budget, which Yale could plug without batting a proverbial eye, having made over $12 billion in endowment returns during fiscal year 2021 alone. Or the University of Pennsylvania’s to Philadelphia: the school has been hoovering up land from the city’s historically black communities for so long that the process has its own neologism, “Penntrification.” Or the University of Chicago’s to the city’s historically black South Side: in the 1930s and ’40s, the university spent tens of thousands to defend racially restrictive covenants in Hyde Park. Today, activists protest the campus police force’s treatment of the local black community. Or Brown’s to Providence: in the second half of the twentieth century, the university’s developments uprooted the Cape Verdean immigrant community of Fox Point. Descendants of those displaced likely work in Brown’s dining halls today.

These private universities qualify as tax-exempt nonprofits because they are thought to serve a civic good. In reality, they occupy land, underpay local workers to toil as janitors and cafeteria servers, employ security forces that harass and surveil residents, and despite small gains in accessibility to low-income students, serve mainly to reproduce a ruling class of junior analysts and McKinsey consultants. Their model relies on real estate speculation and resource extraction to succeed. What’s worse, they have been aided and abetted by every level of government under the pretext of redevelopment and urban renewal. The Columbia expansion would not have been possible without the help of New York State, which in 2008 deemed parcels of the desired land “blighted” and seized them by eminent domain.

The price of USC’s many controversies has been ridicule: administrators at schools like Yale, whose endowment is now over $42 billion dollars, must look down on USC like old-money WASPs sneering at the oh-so-tacky nouveau riche, who insist on parading their money and power out in the open. A quid pro quo scheme? How gauche! But these scandals were produced by the same forces that animate every private university in America: a relentless drive for profit and prestige that treats local residents, and indeed even students, as collateral damage. USC may seem like a laughable anomaly; really, the university is a fun-house mirror parable for higher education in the U.S. today. We should think of USC not as a punchline but as proof of the costs of our current model. And we should ask ourselves: what is it that these universities really owe?

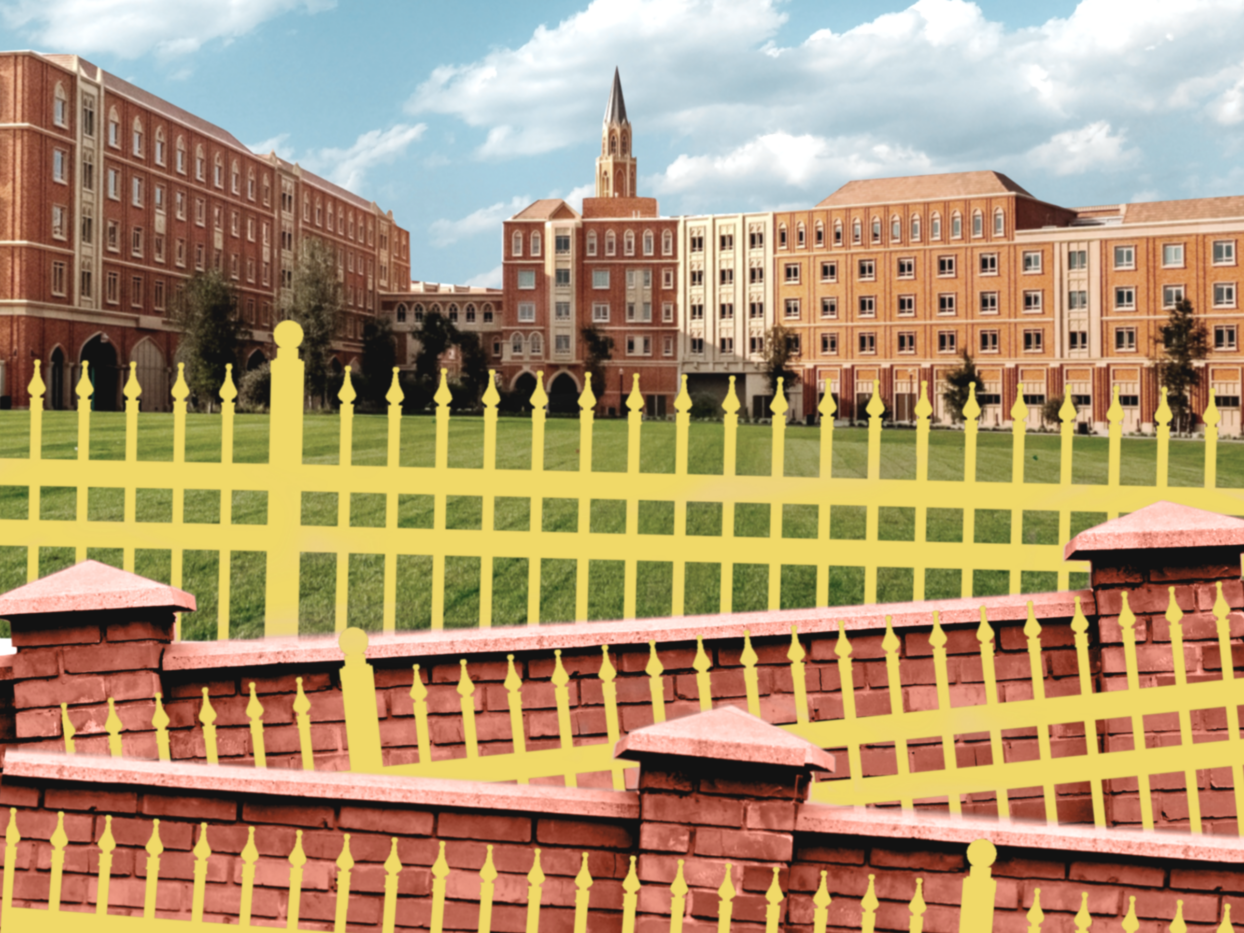

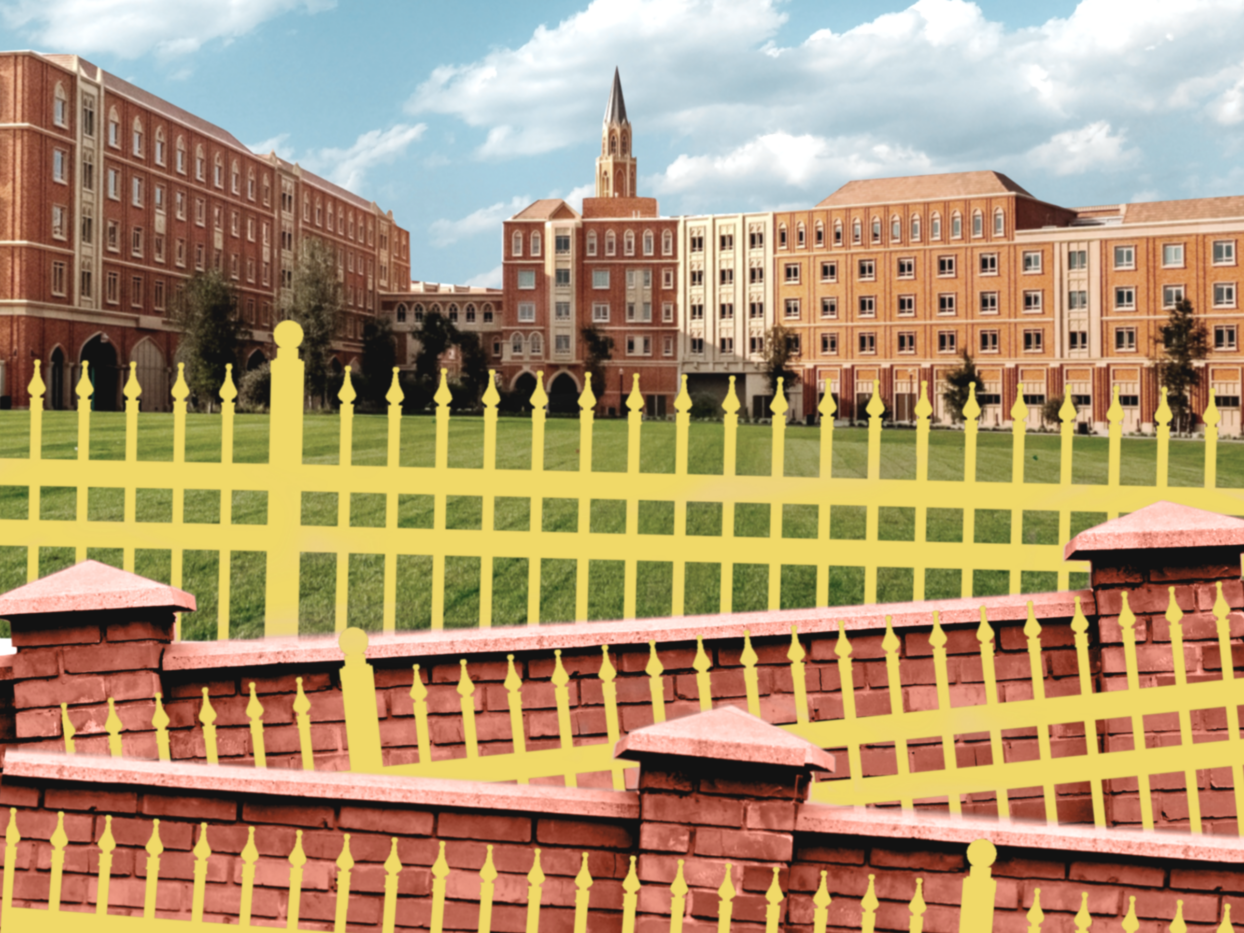

Like essentially every student to matriculate in the last few years, Sasha Urban, who entered USC in 2017 and became one of the school’s most prominent student journalists, found his studies bookended by institutional upheaval. But when he arrived at USC, one of the first things he noticed was the gates. Returning to campus after dark, students would have to exit their vehicles, check in with a security guard, and walk the last fifteen minutes to their dorms. Logistically, this was a minor hassle, made worse if you were returning to campus after break and had to haul your luggage with you. For Urban, it was the first indication that his college considered the surrounding communities enemy territory.

The gates hadn’t always been there — for USC hadn’t always been in the middle of a neighborhood it considered dangerous. The university welcomed its first students in 1880, nine years before Los Angeles established its city council. Unlike most private universities on the East Coast, it was co-ed and theoretically open to students of color from the start, though it would be 37 years before the first black student graduated. But for a long time, USC was an academic backwater, attracting students who were mostly white, affluent, and not particularly distinguished; it was frequently derided as the “University of Second Choice” for college-going Angelenos.

After World War II, as black Americans moved west during the second great migration, racially restrictive land covenants forced many to settle in South L.A. The 1965 Watts Rebellion — borne of years of frustration over systemic racism and police control of those communities — frightened USC’s administrators, who considered moving the campus to Orange County. Then came the brutal beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles Police Department officers in 1991. The violence that followed the officers’ acquittal the following year engulfed the area surrounding USC, leaving 63 people dead, thousands injured, and entire blocks decimated. Students on campus, which had largely avoided damage, printed t-shirts that read, “University of South Central. I Survived the Finals Week Riot!”

In the nearly three decades since the ’92 uprising, USC has grown rapidly in both size and prestige, helped along by two presidents whose strategic recruitment of top faculty and relentless fundraising catapulted the university into the U.S. News & World Report’s coveted rankings of the top 30 national universities. In 2000, an L.A. Times education reporter wrote of then-president Steven Sample: “In the nine years that Sample has been president, there have been many victories, so many in fact that something is dying, and fast: USC’s reputation. It’s not your father’s jock and frat-boy party school. Not anymore.” Sample’s successor, C.L. Max Nikias, turbocharged that process. Journalism professor Larry Gross recalled Nikias’s dictum for new deans at the time: “Your top three priorities are fundraising, fundraising, and fundraising.”

In 2022, it is impossible to overstate USC’s gravitational pull within Los Angeles. The school’s administrators manage an institution that is the largest private employer in the city of L.A. and adds $7.4 billion worth of economic activity to Southern California annually. Its board of trustees is an L.A. power broker short list — it includes Marc Benioff, Salesforce cofounder and coauthor of Compassionate Capitalism; Miriam Adelson, billionaire physician and widow of GOP mega-donor Sheldon; and Steven Spielberg. The board’s chairman is local billionaire Rick Caruso, who is also an alumnus, a proud USC parent (all four of his children attended the university), and a repeat donor. The heir to the Dollar Rent A Car fortune, Caruso made his own money in real estate, specifically malls: he is responsible for “The Grove,” an eerie open-air complex on the Westside, and his single-minded pursuit of a mall in Carlsbad once led him to spend $12 million funding a voter initiative intended to circumvent environmental regulations. He is also constantly toying with a run for mayor.

There was once a time when erstwhile running back Orenthal James Simpson was one of the more controversial figures associated with the university. In February 2016, a student named Darian Nourian wrote an editorial arguing that a replica of O.J.’s Heisman Trophy, the most prestigious award in college football, should no longer be displayed on campus. “You hear USC being associated with a double homicide murder case,” he later told a reporter. “That’s the last thing you want to be associated with.”

Today’s undergrads might envy Nourian, who was blissfully unaware of the tsunami of bad press about to assail his alma mater. It feels safe to affirm, from the vantage point of a few years later, that the public no longer associates USC with the ’90s’ most notorious double homicide. O.J.’s transgressions have been eclipsed by a steady string of scandals first publicized around 2017 and continuing relentlessly into the present day. There have been far too many to recount in any detail, so here’s my attempt at scandal speedrun:

The dean of the medical school is revealed as a habitual meth user and philanderer: at one point, a young sex worker overdoses in his company; later, the infant son of a woman he financially supports and uses drugs with dies after possible abuse or neglect. The next dean loses his appointment after the L.A. Times uncovers a sexual harassment and retaliation complaint against him from years earlier. A program in the medical school loses accreditation after a resident sues a fellow and the school for sexual harassment (and two other women later come forward). George Tyndall, a gynecologist in the student health center whose license plate reads “COEDDOC,” is investigated by the L.A. Times, which discovers a pattern of abuse stretching back decades; the university is forced to disburse $1.1 billion in settlements, the largest such payment in education history. The president, star fundraiser Nikias, steps down only after these cascading scandals make it impossible for him to hold onto his seat; he receives an eye-popping payout and stays on as a professor in Electrical Engineering and Classics. The university then hires lobbyists to influence a bill before the California state legislature that would extend the statute of limitations for the gynecologist’s many victims. In a series of lawsuits, fifty former patients allege that Dennis Kelly, another doctor at the student health center, is a serial sexual predator, targeting gay and bisexual male students. It is later reported that a number of the doctor’s victims had notified the university and received no response, and that the doctor had previously been fired by UCLA, where he had abused at least one patient. The Title IX coordinator is forced to step down after her repeated mishandling of sexual assault cases sparks several more lawsuits — separately, she is sued for retaliating against a coworker who accused her then-boyfriend, also a USC employee who worked in crisis counseling, of non-consensual sexual photography. In response, the U.S. Department of Education orders an overhaul of the university’s Title IX office. A federal sting operation dubbed “Varsity Blues” exposes a scheme between a rogue college counselor, wealthy and in some cases famous parents, and a series of willing henchmen on various sports teams to manufacture athletic accomplishments for mediocre high school students in order to gain their entrance as student athletes. (One of the students, the YouTube-famous daughter of Lori Loughlin, is aboard trustee Rick Caruso’s mega yacht, “Invictus,” when the news breaks.) A lawsuit alleges that the university’s administrators are essentially keeping burn books on faculty who dare to publicly criticize the university. Meanwhile, a series of incidents of sexual impropriety by faculty occur that would have caused a major splash anywhere else but barely register at USC.

And during the fall of 2021 alone: the Ridley-Thomas indictment is soon eclipsed, at least on campus, by news of a scandal involving USC’s Sigma Nu fraternity, some of whose members are allegedly in the habit of spiking the drinks of female visitors to their manse and then assaulting them. The university, it is revealed, has sat on this information for almost a month before releasing it to the public, during which time at least one more student has been assaulted. On November 9, only a couple of weeks after the Sigma Nu news breaks, The Wall Street Journal publishes a story digging into the university’s use of a for-profit company to recruit students for its social work school, where they racked up life-changing debt for a degree that is cheaper and leads to better outcomes elsewhere. The day after that, the L.A. Times reports that U.S. Representative and L.A. mayoral frontrunner Karen Bass had requested an ethics waiver in order to accept a full scholarship to the USC School of Social Work from none other than Marilyn Flynn — not verboten per se, but a tidy illustration of how the university’s officials curry favor with their elected representatives.

These scandals, which range from the salacious and schadenfreude-inducing to the grimly horrific, did not merely arise concurrently to the university’s meteoric ascent in the rankings — they are a direct function of it. The scandal surrounding the dean of the medical school perfectly sums up the ramifications of USC’s misplaced priorities. “They reappointed him, by all accounts, because he was supposed to be good at fundraising,” Professor Gross told me, “despite the fact that a lot of faculty were sending the message: there’s something wrong with him.”

For USC, the solution to every problem has been more development. After the Watts Rebellion, as USC administrators panicked over the fraught location of their campus, the city sprang into action. L.A.’s Community Redevelopment Agency (LACRA) worked to create a redevelopment zone that would allow USC “to expand its campus borders and eliminate surrounding community blight,” according to a paper by public administration professor Ralph Rosado. “With the help of the LACRA,” Rosado wrote, “USC became the largest landowner in the [area].”

In the 55 years since, USC has continued to metastasize outward, a process that has only accelerated over the last two decades. Italophile real estate magnate and Trump mega-donor Geoff Palmer has corrupted the views of many Angelenos with his downmarket Mar-a-Lago ripoffs. In 2014, after buying the land from a local hospital over the objections of residents, he opened the “Lorenzo,” a luxury student housing development just across the 110 freeway from campus. The Lorenzo, which advertises the opportunity to “Live. Learn. Lorenzo” and experience “VIP rates,” acts as a sort of starter apartment to his other freeway-adjacent complexes downtown. You could pick up the keys to the palazzo upon arriving in Los Angeles for college and never leave a Palmer residence until your death.

Though USC has had plenty of negative national press (the L.A. Times won a Pulitzer for its reporting on the gynecologist case, and “Varsity Blues” was late-night fodder for months), the university has seldom been the target of mainstream media criticism for its relationship to its surrounding communities. In fact, some of the reviews it has received have been glowing. In 1999, Time awarded USC “College of the Year,” praising its strategy of “enlightened self-interest” as a kind of symbiosis: “For not only has the ’hood dramatically improved, but so has the university.” The piece noted that over half of USC’s undergraduates volunteered in the community, adding: “For some undergraduates, the encounters [with community members] shatter class prejudices.”

In 2014, USC broke ground on “University Village,” a Google-style campus replete with shops and student housing that looks a little like a fake town on a film set and, with a $700 million price tag, is one of the largest economic development projects in the history of South L.A. The university has consistently framed its new developments as a boon to all — a spin that an L.A. Times business reporter appeared to swallow hook, line, and sinker in a 2017 puff piece on the complex’s grand opening that includes no interviews with community members. The reporter did quote known USC-booster Rick Caruso, though: “It enhances the community to have these shops and restaurants.”

Some locals are more circumspect about the impact of all this construction. “We’re excited that new businesses [are opening] because people are bringing money into the community,” said Gina Fields, chairperson of the Empowerment Congress West Area Neighborhood Development Council (ECWANDC), one of many neighborhood councils established in 1999 in order to help communities of color advocate for themselves at City Hall. “But if we’re no longer there to use those businesses, what was the point in the beginning?”

USC’s trade-off for its massive developments comes in the form of “community benefit agreements,” which require a real estate developer to commit to certain stipulations that are meant to enhance the community around the project in question. In the case of University Village, USC has touted its commitment to hire local workers and donate $20 million to the city’s affordable housing trust. “We’re talking about an institution that is sitting on an endowment of over $5 billion,” Felipe Caceres told me. “Their investment pales in comparison to what they owe the community.” (Frequently, he claimed, USC doesn’t even abide by its community benefits agreements.)

Caceres is an external coordinator at SEIU’s Local 721, which represents public sector workers in L.A. and across Southern California. He’s also part of USC Forward, a coalition that arose after local racial justice and tenants’ rights groups realized that USC was driving many of the phenomena they were organizing to oppose: over-policing, rampant development, and the resulting displacement of longtime black and Latino residents. Their demands, Caceres told me, include immediate union recognition of all campus workers, a $250 million initial investment in an affordable housing land trust for South L.A. residents, and an additional $250 million in scholarship funds for L.A. public school students, or 2,000 fully-funded scholarship slots each year. The university does offer scholarships, Caceres noted, “but how many of those kids are coming from East L.A. and South Central L.A. Unified Schools?”

The group’s final demand is that the university abolish its public safety department. Every occupied territory must have an army, and the area around USC is no exception; the university possesses one of the largest private police forces in the United States. With over 300 employees, its own joint LAPD-USC SWAT team, and an annual budget of around $50 million, the department is captained by a former LAPD gang unit lieutenant, and its public safety officers train at the LAPD police academy. In early 2021, Capital & Main reported that a number of campus officers had come to USC after being stripped of their police duties or leaving after investigations into misconduct. Included among them: an LAPD sergeant who engaged in repeated racist harassment of a black officer who worked directly under him, a Santa Ana Police Department officer who beat a suspect to death, and an officer who threatened to plant crack cocaine on a person he was interrogating.

After a series of large donations allowed the university to expand its Health Sciences campus in East L.A., with a plan to grow by more than three million square feet between 2011 and 2026, USC is now encroaching upon Chinatown and the predominantly Latino neighborhoods of Lincoln Heights and Boyle Heights as well. As one community activist told Capital & Main: “These buildings appeared and then, boom — we get campus police everywhere.”

After an on-campus shooting in 2012, USC effectively became a gated community, erecting fences around the campus’s perimeter, requiring guests to register with the university in advance of visits, and forcing students to scan their fingerprints in order to get into their dorms. But the university’s “sphere of influence,” as Caceres put it, is 2.5 miles around the campus — which stretches into four separate council districts. Additionally, around 70 “security ambassadors” patrol the areas near USC daily with radios in case they “observe suspicious or unusual behavior,” according to a USC annual safety report. Caceres said that community members have consistently complained about harassment and racial profiling from ambassadors and campus safety officers, even when they’re nowhere near campus. And their presence transforms on-campus spaces that are meant to be open to the community, like University Village’s Trader Joe’s and Starbucks, into inhospitable zones. “It’s a citadel unto itself,” Caceres said of the new complex. “You can walk in there — whether you feel comfortable walking in there, and whether one of the ambassadors asks you why you’re there within five minutes, is another question.”

Incredibly, despite its many recent building projects, USC doesn’t have anywhere near enough units to house its student body population, which has risen from 27,000 to nearly 50,000 in the last 30 years. “The competition is so high now because of the influx of students,” said Fields. “People are being displaced.” This growth has created a strong incentive for private developers to remodel and rent to students for several times what they could extract from working-class tenants. In 2017, in a particularly egregious example of this phenomenon, a developer purchased seven buildings on a single block of Exposition Boulevard, one of South L.A.’s major thoroughfares, attempting to evict more than 80 tenants from rent-controlled housing. Eviction notices informed residents that the building would be remodeled and “rented exclusively to USC students.”

In April 2019, USC Forward organized a protest on campus. People set up camping tents to symbolize the displacement that the university had accelerated. Eventually, they approached then-University Chief of Staff Dennis Cornell and presented him with a sleeping bag covered with demands. Sasha Urban was covering the event as a student journalist, and he remembered being struck by what happened next. Cornell chatted with the representatives from USC Forward for several minutes, noting that the university had addressed the concerns of graduate student workers, who also belong to the USC Forward coalition. But then Cornell announced that he wouldn’t address concerns from residents. “He said, ‘You’re actually not in this community,’” Urban recalled. “He looked all these people in the face and was like, none of you live here.”

For many neighboring residents, such disinterest cannot be mutual: they have a fierce stake in what the university does because it impacts their daily lives. This asymmetry was underscored during the Los Angeles City Council’s recent redistricting process, a slow-motion bureaucratic nightmare that managed to leave practically everyone unhappy and posed an especial injury to District 8.

L.A. City Council Districts 8, 9, and 10 span South L.A., encompassing many of the city’s historically black neighborhoods. Each district has been represented by black politicians ever since 1963, even as all three, and especially District 9, have become increasingly populated by Latino residents. During the last redistricting cycle, in 2011, the District 10 representative negotiated the transfer of the lucrative downtown area, with its high concentration of commercial buildings and new developments, away from District 9. Next, USC was moved from District 8 to District 9, a consolation prize for the loss of downtown, leaving District 8 struggling to accept the loss of its only economic hub.

During the 2021 redistricting process, District 8 vowed to regain control of USC. Through her role representing “stakeholders” in Districts 8 and 10 at ECWANDC, Fields supported the move; at an October city council meeting, she said it would “give the neighborhood increased leverage in addressing rampant student housing development and the resulting displacement.” Unsurprisingly, District 9 protested. After a while, it appeared as though the two districts had reached a compromise: the 9th would hold onto USC, while neighboring Exposition Park, a huge public space that comprises two stadiums and several museums, would go to the 8th. But then USC weighed in. A representative announced that the university’s only priority was to remain united with Expo Park. “That blew up the whole plan,” Fields said. “Money talks, and the money behind USC said no.” In an ironic turn, she added, South L.A.’s negotiating and voting power was hobbled by the absence of one Mark Ridley-Thomas — the District 10 council member, who had just been stripped of his public duties following news of the federal indictment.

At the end of the day, this battle is mainly about who gets to receive community benefit agreements. Having USC back in District 8 would allow residents no more control over the university’s displacement and gentrification than District 9 residents have enjoyed over the past decade. Fields threw herself into the ring on the redistricting fight, but not without some bitterness about the fact that L.A.’s historically black communities were being forced into a zero-sum game in order to obtain a modicum of agency over the university’s impact on their neighborhoods. “It’s a little bit heartbreaking,” she said. “It feels like the black districts are left fighting for crumbs.”

These days, having shed the “University of Second Choice” moniker, USC is more often snarkily referred to as the “University of Spoiled Children,” and there is no doubt that many students who fit that description wander its campus. The estimated cost of on-campus attendance is $81,659, and the university is not doing itself any P.R. favors by continuing to dub its legacy offspring “SCions.” But most students, rich and poor alike, are just looking for a decent education that will allow them to get good jobs afterward. In its rush to ascend the rankings and line its endowment, the university has not only run roughshod over the working-class black and Latino residents who call its environs home. It has also acted with consistent disregard for the people it actually does consider part of its community.

USC’s recent unwillingness to publicize credible accounts of drugging and assault at Sigma Nu put more students in harm’s way and made the administration complicit in future assaults. Tyndall, the serially predacious gynecologist with the creepy license plate, and Kelly, the doctor who targeted gay and bisexual male students, were abusing patients for decades — some 17,000 women are included in the Tyndall settlement. And the university’s hostile approach to its workers and neighbors predictably hurts grad student workers and students and faculty of color as well.

Then there’s the psychic toll of attending a university burdened by so many scandals. Sasha Urban spent the summer of 2019 reporting on the allegations against Kelly through a new initiative at USC’s journalism program, publishing his findings in Buzzfeed News that August. When we spoke in early November 2021, just a month before his graduation, Urban told me he’d lately had to take a step back from covering misconduct at USC for his own mental health. “There was a time when I could list, off the top of my head, ten scandals in chronological order from 2017 to 2019, and I can’t do that anymore,” he told me. “I’ve kind of wiped them from my memory.”

Plenty of students are also angry about the displacement that they have inadvertently exacerbated. In 2013, when USC erected its gates, a campus group called #USChangeMovement petitioned the university to take them down, and students frequently address the university’s role in gentrification and racial profiling in campus publications. “There’s a lot of people at USC who care a lot about the surrounding community, who do food drives and community fridges and go to Skid Row and work with organizations there,” said Urban. “Those people don’t really have an answer when they’re asked, why is my family getting kicked out of our apartment? No matter how much good is being done on the ground, if university leadership is not invested in the health and well-being of the community, both inside and outside of the campus, it’s never going to fully happen.”

Neither have the school’s faculty members rejoiced to find their ivory tower covered in soot. Although USC has paid handsomely to lure star professors away from other institutions, once on campus, many of them discover an environment hostile to academic freedom, shared governance, and transparency. In 2018, fed up with the “drumbeat of scandal accumulating around the university,” Professor Gross helped form the group Concerned Faculty of USC, which published several open letters regarding the administration’s corruption, and ultimately advocated for the ouster of President Nikias. But even after Nikias’s departure and other reforms instituted by the board of trustees, Gross remains skeptical about the administration’s commitment to change. “When the president and provost meet with the faculty, they’re giving prepared PowerPoints about how wonderful everything is,” he said. “There’s very little sense of real dialogue.”

When asked for comment, USC responded at length. “USC is committed, more than ever, to community partnerships and building a shared vision with our neighbors,” read its statement. “We partner every day to support healthy, vibrant and engaged communities.” The university, it continued, uses “resources and expertise with direct guidance from community members” and works to address “issues including gentrification and displacement.” The statement directed me to a long list of “community programs that serve youth and families,” including the USC Good Neighbors Campaign, which “contributed $1.3 million in 2020 to support local nonprofits and programs” and USC’s Bridges to Business and other nonprofit resiliency programs that “have supported hundreds dozens [sic] of small, diverse businesses and nonprofits with technical expertise and capacity development.” With regard to specific allegations by USC Forward, the university stated, “USC engages with all community stakeholders, including USC Forward. We continue to welcome their participation and good faith collaboration to strengthen the communities we all serve.”

At the heart of USC’s displacement and surveillance of its surrounding communities is a belief that the university is exempt from the normal rules of civic engagement because of what it represents: the life of the mind, social mobility, meritocracy. At the heart of the administrative misconduct that has played into most of USC’s scandals is a wanton disregard for the experience of students and faculty — and, by extension, the very same qualities that universities supposedly represent — in favor of fundraising and reputation management. This paradox underwrites every private university in America, whether or not it is beset by the same scandals that have lately engulfed USC.

It’s clear that there is a debt here, and I’m not just talking about the student loan crisis. If the university met USC Forward’s monetary demands, it would do much to materially benefit the community. But for USC to do so would require it to voluntarily recognize the harm it’s done.

Many prestigious universities have attempted versions of this, but when you scrutinize the numbers, these gestures reveal themselves for what they are: ablutions, not meaningful attempts at restitution. In 2020, the University of Pennsylvania announced a $100 million gift to the city of Philadelphia’s public schools, to be disbursed over ten years. Local activists weren’t fooled: two groups estimated that if Penn paid property taxes, the “gift” would increase ninefold. Columbia has promised to invest $150 million in the surrounding communities to mitigate the impact of its multi-billion dollar expansion. But a taxation expert told New York Times columnist Ginia Bellafante that if the university were taxed on its real estate holdings as though it were a bank, it would owe around $320 million for 2021 alone. In 2019, Harvard failed to meet Boston’s requested sum for the city’s “payment in lieu of taxes” program, which asks nonprofit organizations possessing more than $15 million in property to help offset municipal costs, for the eighth year running. That year, the university reported contributing $10 million to the city, but over $6 million of the money was in “community benefits” that the university got to choose itself, and one of the things it chose was maintaining its own arboretum. Its endowment that year? $41 billion. People are fond of saying that Harvard “has more money than many third-world countries,” but the university’s current endowment, $53.2 billion, is approaching the GDP of Croatia.

In the past few years, gifts like these have often been accompanied by acknowledgements of harm done many centuries ago: slave labor employed or profited from, eugenicist thought expounded, students of color turned away. These affairs tend to be pageants of liberal guilt, each a “hard look” or “reckoning” that ends with a commitment to give a few more million dollars to the city’s public schools. The more firmly the sin is cemented in the past, the more attention strays from the sins of the present. In 2006, after Brown released a report detailing its complicity in slavery, it pledged to contribute $10 million to a Providence public school fund. But it took the school 14 years to come up with the money, which it then crowed about as though no time at all had passed. This fall, Yale’s president formally acknowledged the university’s ties to the slave trade and promised to increase payments to New Haven. At the event, the poet Elizabeth Alexander urged Yale to “invest, not millions, but billions in the city of New Haven.” Shortly thereafter, Yale announced an “unprecedented” new arrangement with the city, upping its previously agreed-upon payments by $52 million over six years, or a little less than $9 million per year.

In a press release, a representative hammered home the “voluntary” nature of the donations (the word is invoked 13 times, not counting photo captions), and the fact that they are “over and above” previous sums. And it is a lot of money — until you compare it to the size of Yale’s endowment. Then it starts to look more like Jeff Bezos donating $100 million to a food bank: nice, but neither a heavy lift nor a solution to the problems his own company has created.

These are private sector solutions, after all — charity instead of taxes. And like most charity, it works more to assuage the conscience of donors than to change the circumstances of their recipients. The Covid-19 pandemic has caused utter misery amongst cities’ poor and working class residents; meanwhile, universities’ endowments have skyrocketed. Columbia’s return on its endowment this fiscal year was 32 percent, two percentage points below the median for universities. Yale’s was 40 percent, Brown’s an astonishing 51.5 percent. “By any standard, Fiscal Year 2021 marked an extraordinary single-year return for the Brown endowment,” the university gloated.

There’s simply no way to take stock of the capital accumulation of these institutions without concluding that one of their main functions is to amass wealth. In doing so, they draw from the communities in which they’re situated, and their largesse will never right that imbalance — it’s not even the goal.

So why are we allowing them to choose how much they give? For too long, the government has explicitly or implicitly helped universities extract resources from the communities around them. One preliminary solution to this mess would be to revoke the nonprofit status of private universities, which allows them to skirt many, many forms of taxation. Such a reform could allow state and local governments to raise literally billions of dollars in revenue. “Change the tax code” is a far milder rallying cry than the outright abolition of private universities, which plenty of others have already demanded. But if done right, it could probably do more to actually benefit communities that have long suffered from state disinvestment and private sector plunder.

And as for USC: if the university seriously wants to change its ways, it should grant USC Forward’s demands, fire its administrators and hand over control of the university to an elected group of faculty and students, replace the billionaires on the board of trustees with community members, stop expanding the student body and figure out how to sustainably house its existing population, and reserve 20 percent of the seats in each incoming freshman class for L.A. public school students. If not, well, USC provides as good a candidate for exemplary dissolution as any.

Piper French is a writer living in Los Angeles.