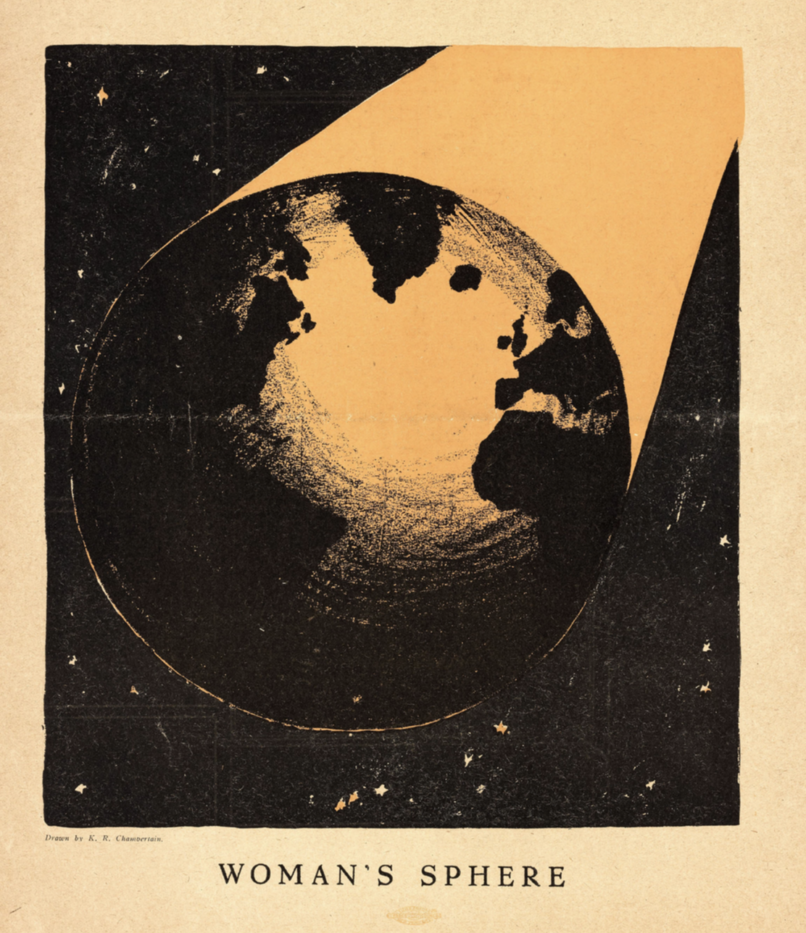

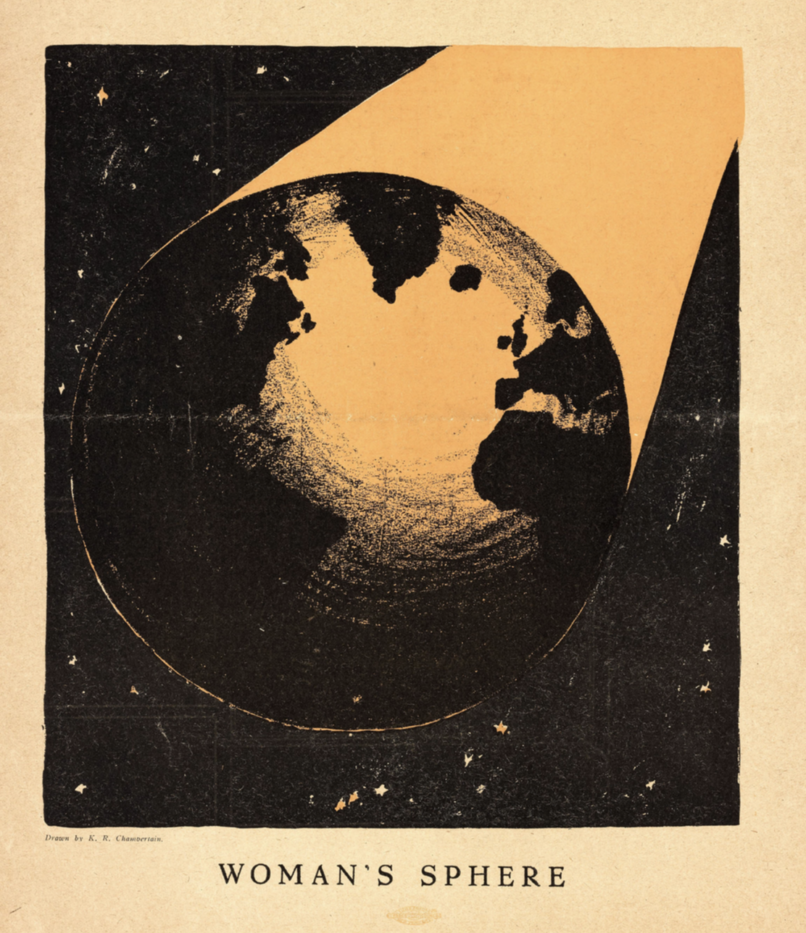

Back cover of The Masses, November 1915, Women's Citizenship Number

Back cover of The Masses, November 1915, Women's Citizenship Number

Even before he was elected, CNN reported, Donald Trump had “awakened a feminist revolution in America.” The Access Hollywood tape in which he uttered the phrase “grab ’em by the pussy” was greeted as the end of the election, almost universally expected to spark the backlash that would ensure his defeat and usher in a new era for women. The future was female, and for a brief moment, even Fox anchor Megyn Kelly was considered an ally in the cause. Instead, Trump won the election with the support of more than 50 percent of white women, a fact that continues to astonish, perhaps most of all, the white women who did not vote for him.

The much-heralded “revolution” did arrive after the election, in the form of the Women’s March, the largest single-day protest in U.S. history, and, nine months later, #MeToo, which seemed poised to channel collective anti-Trump rage into a new code of conduct for workplace sexual harassment. But the energy that animated these actions has since faded. The Women’s March grew less crowded each successive year, its trademark pussy hats consigned to attics and museums; #MeToo quieted after dethroning a series of powerful men.

The feminist tide wasn’t strong enough to stop Joe Biden from beating out an unprecedentedly female field for the nomination, but it did force his hand on a pledge to choose a female Veep — an insulting tokenization that found its mirror image in Trump’s promise to select a female replacement for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the grand dame of contemporary feminist iconography. So far, the Biden administration has leaned hard on its gender diversity. Asked last week about the Reddit-driven stock market activity around GameStop, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki started off by noting she was “happy to repeat that we have the first female Treasury Secretary.”

All of the pro-woman symbolism does next to nothing for the many women who are unemployed, overworked, and struggling. Nurses and teachers — some of the pandemic’s most heavily exposed workers — are overwhelmingly female. The gender dynamic of the much-discussed shift in labor from manufacturing to retail and healthcare meant that working-class women were most likely to be impacted by shutdowns, layoffs, and hazardous essential work. Nor was remote work an equal challenge for white collar men and women. As schools closed and parents became responsible for 24/7 childcare, the burden fell on women — with only three percent reporting that their husbands were doing more of the homeschooling work. The jobs numbers reflect that unfair division of labor: over 100 percent of net jobs lost in December belonged to women, a bewildering statistic made possible by the fact that men’s employment has, during the same period, increased in aggregate. A sizeable number of the newly unemployed women — almost 2.1 million — have dropped out of the labor force altogether since the pandemic began, meaning they are no longer looking for work. In the past year, women’s participation in the workforce plummeted to its lowest level since 1988. These statistics don’t count women who have been passed over for promotions, gone part-time, taken leaves of absence, or simply performed poorly at their jobs, delaying or derailing their careers. And staying at home poses its own risks. Intimate partner violence has been called “the pandemic within the pandemic.”

Even prior to Covid-19, the statistics were universally bleak. After a movement against sexual violence on college campuses (a signal effort of the Biden vice presidency), not much changed: the rate of sexual violence actually increased between two anonymous nationwide surveys conducted in 2015 and 2019. There are fewer places to get an abortion now than at any time since Roe v. Wade, and the U.S.’s maternal mortality rate is the highest among developed countries, with Black women more than twice as likely to die giving birth. 2020 was the deadliest year for transgender women and gender non-conforming people since the Human Rights Campaign began tracking the violence in 2013.

There’s a disconnect between that image of American life and the model of feminism that dominated the 2010s — a feminism where celebrity, corporate values, politics, and theory mingled uneasily. Ivanka Trump released a book called Women Who Work. The “squad” was either Taylor Swift’s friend-group or four newly elected progressive women in Congress. The phrase “emotional labor” was applied to so many ordinary activities it has been all but divorced from its original meaning. Even the call for an “intersectional feminism” — a necessary corrective to “corporate feminism” or “white feminism” — was marshaled into a push to hire women of color into prominent roles, while the issues that affect most Black and brown women remain unaddressed. The “girlboss” has been killed off so many times that killing her off is passé.

If it’s become unfashionable, in intellectual circles, to speak of a feminism that celebrates work, ambition, and vocation, such rhetoric is alive and well on the national political stage. “The First But Not the Last” is the inspirational phrase stamped on a new line of Beats by Dre headphones designed by Kamala Harris’s niece, Meena. Her children’s book, Ambitious Girl, came out this month, and her fashion-turned-media company Phenomenal Woman (named after a Maya Angelou poem) was described last week in People as a “booming, celeb-endorsed lifestyle brand.” Harris’s step-daughter, for her part, signed with IMG models after turning heads at the inauguration in a $5,000 Miu Miu coat. You, too, can buy a $380 cashmere sweater embroidered with the curly lower-case script “first but not last” or “madam vice president.” (Other options include “my voice is vital,” “breaking glass ceilings,” and “not today patriarchy.”)

Amid the sloganeering, profiteering, and general lameness, it’s hard not to want to distance yourself from the feminist mainstream. At the height of #MeToo, dissent was taboo but eagerly anticipated, even on the left: thousands of subscribers paid to support the female podcast hosts daring enough to proclaim their love of Woody Allen movies and their disdain for feminists. Now, this kind of provocation barely registers. Asked recently what she thinks of feminism, a debut novelist said, “Who cares?”

We’re not quite ready to cede all of feminism to the administration headed by the man who presided over the Anita Hill hearings. There has to be a critical middle ground, we’re convinced, between symbolic feminism and contrarian antifeminism. In this issue, we’ve tried to find that space through, among other things, honest criticism of the market trends that have seeped into the feminist discourse of the Trump years.

In “A Pool of One’s Own,” Noelle Bodick analyzes the female friendship trend in group biographies that reinscribe sisterhood into the history of modernism. “Missing from the female friend trope is any coherent account of power outside the friendship,” she writes, “that is, other than the power of female friendship to uplift and the countervailing power of boorish men to tyrannize.” Marella Gayla parses the appeal of the complex female characters touted by Reese Witherspoon’s entertainment empire. “Many books in the Witherspoon orbit are propelled, to varying degrees, by the much-discussed phenomenon of ‘women’s anger,’” she writes. “Anger with idiotic men and the hollow promises of domestic life, with the traitorous cruelties enacted by other women, with the indignities of being overworked and underestimated.” Riffing on the term “Karen,” which has claimed its place in the popular lexicon as slang for a racist white woman, Carey Baraka looks back at the “Original Karen” — Karen Blixen, author of Out of Africa — and her long shadow in contemporary Nairobi, and especially the neighborhood that borrows her name. Our short story, by debut novelist Amber Medland, visits a woman with a stultifying office job and a boyfriend she met in a self-defense course as she tries to ward off a lonely man’s clumsy advances over a bowl of papadum.

In our Dispatches section, we audit a wide range of cultural responses to the Trump presidency. Some entries, like Sophie Haigney’s short essay on Megyn Kelly and a portrait of Trump in menstrual blood, consider the explicitly feminist reactions to Trump. Others, like Merve Emre’s dispatch on contemporary literature, Blair McClendon’s on film, Sasha Frere-Jones’s on pop music, and Matt Christman’s on comedy, broaden the scope.

The remainder of our issue digs into questions outside of feminism. In her essay on Rumaan Alam’s novel Leave the World Behind, Hannah Gold encourages us to ask more of contemporary fiction. Jonathon Booth, meanwhile, provides a corrective to the popular leftist assumption that today’s police forces evolved from Southern slave patrols. We spoke with Nikhil Pal Singh about the “1619 Project,” Twitter wars, and the state of both the Democratic Party and the GOP. Daniel Bessner takes us through how Cold War history is represented and absorbed in the Call of Duty video game franchise. Sam Adler-Bell takes a hard look at Anthony Fauci’s record, casting doubt on the liberal beatification of “America’s Doctor.” In an overview of the vexed history and contemporary reality of public lands in the United States, Nick Bowlin asks us to reimagine a commonwealth ideal. Surveying recent publications that try to characterize our generation, Kiara Barrow argues that income inequality is a bad metric for understanding millennial precarity. Our poem, by Jackie Wang, locates “the texture of the twenty-first century” in a shadow. And in our Mentions section we review, among other things, the Q Shaman’s Zoom Classes, “Most Stuf” Oreos, and Sofia Coppola’s youthful Comedy Central adventures.

The future may or may not be female, but our women-led magazine is excited to be a part of it. To all who’ve read, subscribed, and supported us in our first six months: thank you.