The first print issue of The Drift is almost exactly eighteen months overdue. At the beginning of March 2020, we were gearing up to launch our magazine. We had edited twelve pieces, picked out our fonts, run our fingers over paper stock and made final selections. The idea, then seemingly foolproof, was to order a shipment of magazines to one of our apartments and recruit friends to help us carry them upstairs and insert individual issues into envelopes addressed to whoever was willing to subscribe to a publication that didn’t yet exist.

That plan — and about half the content of our in-progress issue, which at the time featured essays on workplace sexual harassment trainings and the racial politics of queer nightlife — was rendered moot practically overnight. The virus that we were somehow confident would not interrupt our twenties (Competent people were taking care of it! The CDC was on the case!) had arrived.

On March 16, a team at Imperial College London released a study containing the data that had apparently already scared Boris Johnson into taking the novel coronavirus seriously. In the United States, people who had never before encountered the term “Imperial College London” were suddenly calling for the “non-pharmaceutical interventions” (population-wide social distancing, case isolation, household quarantine, and school closures) it proposed. Colleges dutifully began sending their students away, and offices told employees to expect to work from home for four, maybe six weeks — though what the study actually said was that if we did impose these measures, they would need to be maintained for “potentially 18 months or more,” during which time “transmission will quickly rebound if interventions are relaxed.” In other words, it was clear in March 2020 that once we began to shelter in place, there would be no point at which it would make sense to open back up until, roughly speaking, September 2021.

No one seemed to read the fine print. We repeated the mantra “flatten the curve,” which meant we could space out when people were hospitalized, not how many needed hospitalization — but we pretended it meant something else. With al- most no notice, we expected parents to provide full-service homeschooling during the workday, college students to return to their childhood bedrooms, casual couples to move in together, single people to practice celibacy, residents of nursing homes to remain confined to their units. Anything short of total compliance was selfish: this period was a state of emergency, not real life.

After so long, it can be difficult to distance ourselves from the decisions that were made early on, to remember that the global response to Covid-19 was historically unprecedented and not at all inevitable — the result of a confluence of political, technological, and scientific factors that allowed us to abjure social contact for a length of time previously unimagined.

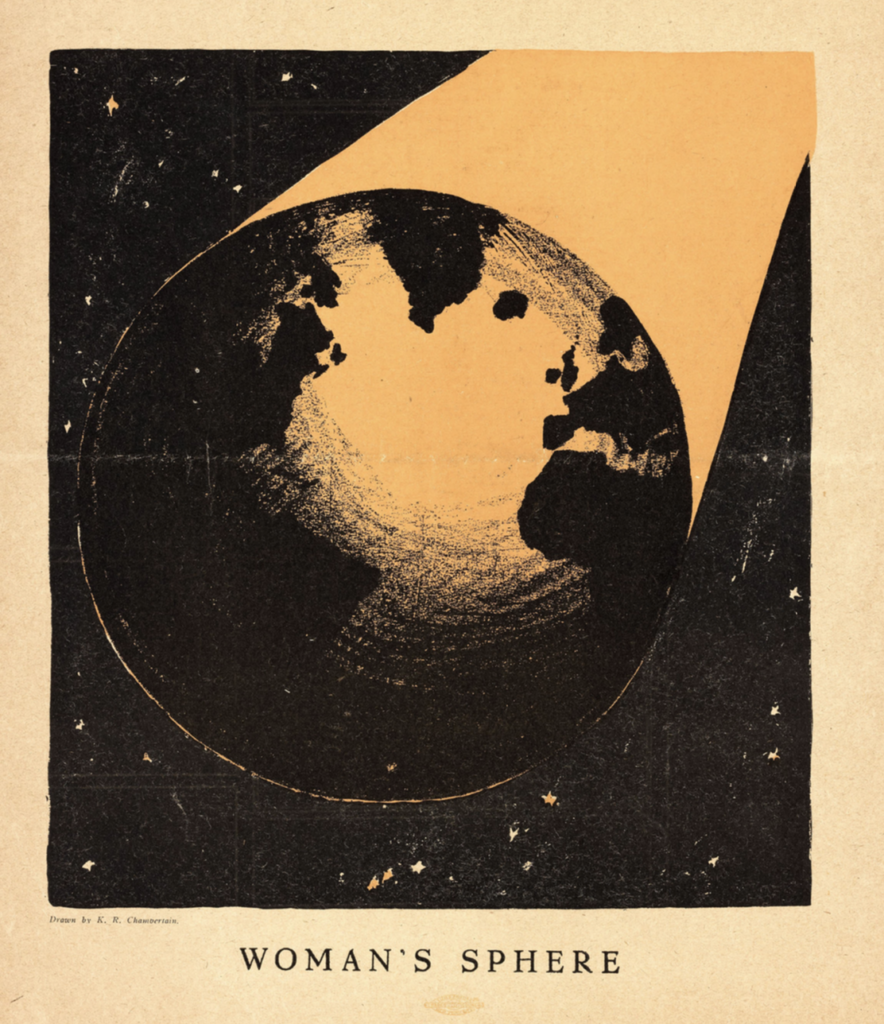

Welcome to Month Eighteen. For a while it looked like the pandemic would end, at least for Americans — that once we dutifully lined up for second vaccines and waited our two or three extra weeks, life could return to normal. But normal, after the hyper-social overcorrection of this summer, remains a shaky concept. Our ongoing state of overlapping crises is routinely described in apocalyptic terms — it’s no longer uncommon to hear, on a near-daily basis, that we are “living through the end times.” But there is no end in sight. Hurricane season turns into fire season, and the virus continues to mutate.

The political change that once seemed unavoidable, after such a profound shock to the system, has not materialized. The radical promise of the Black Lives Matter protests dissipated into a winter indoors; while Roe v. Wade crumbles, the feminist movement feels alarmingly unmoored; money continues to be redistributed upward, as eviction freezes and expanded unemployment benefits are phased out. The pandemic is no longer a state of exception but a new fact to assimilate into an already grotesquely unfair picture of how the world works.

Meanwhile, the culture churns on. “Pandemic fiction” has ceased to sound gimmicky: no portrait of the early 2020s would be coherent without an acknowledgment of the profound rupture the past year and a half have represented. Television, meanwhile, has bifurcated, with some shows adding pandemic-related crises to their plotlines, and others veering off into an alternate universe in which Covid-19 does not exist. New movies and albums seem to float across our collective field of vision for a while, and then recede. Behind the scenes, executives have been holding out on us, awaiting the possibility of real theatrical releases. For the literary press, it’s been easy enough to continue business as usual — there have been new books to review, new battles to be waged. The most urgent issues of the day apparently include: why fiction should or shouldn’t be moral, how bad it is to identify with characters in books, and whether reviews that deal with multiple books at once are a scourge that ought to be obliterated.

Even before our plans were upended, print was an anachronistic project, and it’s no less so now. But we won’t pivot to TikTok, or sell subscriptions in Dogecoin. We’re moving in the opposite direction, having spent the summer translating what has been an online publication into the following pages. We believe that reading should offer a break from the barrage of links and tabs and group texts — an opportunity (corny as it sounds) for deep, slow engagement with ideas. During our editing process, we frequently annoy our writers with comments like “Explain for people who have no background in this subject matter!” and “Rephrase for readers who are not extremely online!” In our view, good writing doesn’t require its audience to be fluent in the academic terminology du jour or the latest Twitter debates. It doesn’t rely on strings of hyperlinks to provide evidence for its claims. Its readers should not need to resort to Google to follow along.

In this issue, we’ve tried to take a clear-eyed and jargon-free look at the systems that are failing us — and the quick fixes that are too often substituted for actual change. Jake Bittle argues that boycotting Amazon will do little to support workers and even less to halt the churn of a global shipping industry that has catastrophic consequences for the environment. Nicholas Whittaker, meanwhile, explains why capitalizing “black” is a superficial and misguided concession. While buying liberal-branded picture books and watching doctrinaire documentaries might feel satisfying, Sophie Haigney and Blair McClendon show, they desensitize us to nuance. Britt H. Young reports on members of the Ethiopia diaspora who tried to hack the pandemic, proving that “digital disruption” is sometimes a new face of imperialism. But the old forms of imperialism still persist: our recent withdrawal from Afghanistan, Samuel Moyn tells us in an interview, will not put an end to U.S. hegemony. Nor will it dampen the enthusiasm among policy wonks for pursuing an ill-defined sense of “democracy,” writes Parvin Khan. Just as American exceptionalism provides cover for atrocities abroad, flattering portraits of the wealthy paper over the indefensible chasm between rich and poor — a set of representations David Klion tracks in his survey of the career of Josh Schwartz, the creator of The O.C. and Gossip Girl.

“The system was breaking down” is the opening line of John Ashbery’s The System. In an essay on Ashbery’s legacy, David Schurman Wallace takes stock of the state of contemporary poetry. Our short story, by Hannah Gold, is too inventive to fit squarely under the heading of “pandemic fiction,” but it doesn’t omit the reality of Covid either. We have two poems in this issue: the first, by Greg Nissan, filters the sunset through a glitchy consciousness, and the second, by Elisa Gonzalez, gestures slyly at one of our most dysfunctional systems through “the problem of Mass Incarnation.” In our Dispatches section, we investigated further, asking incarcerated writers to tell us about their experience of the pandemic. Since it’s our first time in print, we’re also including a sample of content from our earlier, online-only issues — a look back at our first year and perhaps something of a time capsule, a way of making sense of this exceptionally strange year.

Printing The Drift — and carving out a place for new writers and challenging ideas — is only possible because of the tremendous outpouring of support we’ve received in our first year. To our subscribers and devoted readers: thank you, and we hope you’ll find everything you love about The Drift in these pages. If you’re encountering us here for the first time, you’re in too deep now. Might as well keep reading.