It’s not exactly a fun time to start a magazine, nor is it a convenient one. A magazine is by definition an optimistic, social project, and the past few months have found young people fairly hopeless and dramatically isolated—alienated all over again by an undemocratic political system and a hollowed out, dysfunctional government. We’ve done our part, asked to wait out the virus indefinitely; to wonder when we’re going to lose our jobs, if we haven’t already; to stay home; to vote, as though that might solve any of it.

The protests—spontaneous, decentralized, everywhere—have been more radically imaginative about the horizons of political possibility than anything we might have predicted during the bleak months that preceded them. They are a direct reaction against the brutality of a police force that regularly murders Black Americans with impunity, this time amplified by the rage of a generation that’s discovered all over again that we live in a failed state with a deluded national mythology. While the government botched the response to coronavirus on every level, it maintained the infrastructure necessary to terrorize its Black citizens. The same protective measures that had been declared illiberal and impossible when it came to containing COVID-19 were deployed to stifle the outcry and provide cover for further state violence.

Back in the winter, we were ready to vote for the first serious socialist candidate for national office since Eugene Debs: we still believed that voting for a president could mean something other than harm reduction. That belief was deflated at roughly the same time as the economy tanked and we began to lose jobs, social lives, grandparents, parents, and friends. Out of the most female Democratic primary field ever, we’re left with a nominee who presided over the Anita Hill hearings and has been credibly accused of sexual assault. Elizabeth (“Nevertheless, she persisted”) Warren, heir to the Women’s March movement, marshaled the language of believing women against Sanders before publicly stating she did not believe Tara Reade in a groveling attempt to secure the vice presidential slot.

The list of reasons for despair is long. The list of arguments against starting a magazine in 2020 isn’t terribly short, either. But watching the existing magazines fumble their responses to the pandemic and then chaotically reorder their mastheads, we’re more convinced than when we started: it’s time for something new.

If every crisis is an opportunity, the comfortable classes used Covid-19 as a chance to cosplay ration-era hardship—baking sourdough, hoarding Rancho Gordo beans, and growing scallions as though the supply chains had actually collapsed.

The glossies did what they do best, offering a profusion of indoor lifestyle content. Homesteading recipes abounded, and we were inundated with lists of products and services that might make quarantine more bearable. T: The New York Times Style Magazine advised readers to “upgrade your working-from-home look,” linking to a $345 “Homecoat” in a color called “Dogwalker,” as well as a €550 “bourgeois sweater.”

Behind the scenes, the media faced a genuine crisis over and above its ordinary instability. Publications folded, mass layoffs ensued, and with months of pre-written content suddenly obsolete, the remaining magazines were left scrambling for new material. A week into the pandemic, editors at every vaguely literary or intellectual outlet seemed to decide it had fallen to them to solicit first-person accounts of quarantine for the benighted historical record. Each made the same calculus: while they couldn’t compete with the actual news (which was all anyone wanted anyway), they did have at hand the minds who could make sense of the times. All at once, they engaged in an arms race to recruit the literary talent, who then proceeded to churn out a collection of mundane, self-pitying essays. The problem was that, as these missives made clear, writers were the ones least affected by the changes. They were accustomed to working from home, mostly solitary by choice, and either comfortably ensconced in cushy jobs or already living precariously. And their observations about coronavirus were the same as everyone else’s—they had no special insights to offer.

Some took for granted the universality, at least among their readers, of their new WFH reality. A New Yorker staff writer wrote, “What I did today is the same thing, I hope, that you did,” before rattling off a laundry list of activities like yoga and cat-petting. But the most intrepid diarists engaged in self-conscious attempts to render their particular derangements interesting enough to write about. “I have discovered how much I like to say the word ‘Fauci,’” another New Yorker staff writer admitted. “I walk around my apartment after the President’s press conferences, chanting it like an efficient mantra, or a Dada acting exercise. ‘Fauci. Fauci? Faucifaucifaucifauci. Fauci!’” While safely tucked away in a rural getaway, a writer in The New York Times Magazine began, as an experiment, “squatting before and around my computer as though it were a campfire, with glutes aflame and feet unshod.” She describes eating “without using my hands or any utensils, like a dog, just to see what it was like,” and “sitting quietly on the porch cloaked in seeds.” Does coronavirus have neurological symptoms? (In fact, one n+1 editor with an actual Covid-19 diagnosis reports: “My mind feels shriveled, and I imagine the gray matter pickling.”)

The more highbrow the publication, it seemed, the more tone-deaf the quarantine content. The New York Review of Books addressed the thorny problem of dating, issuing the verdict that it was “complicated—now more so than ever.” Relationships, at least as far as the NYRB masthead goes, indeed seem cause for concern. The same editor bemoaned “catching feelings” for someone who wasn’t “ready for a relationship.” Another writer reported hopefully that, in quarantine, “my husband and I have actually learned and grown.” The evidence? “Some evenings now, he even initiates conversations.” Elsewhere in the Review, the crisis over whether or not to apply lipstick in quarantine reminded a writer of something she read on the Yad Vashem website about how female victims of the Holocaust wore makeup.

The Point, whose quarantine journals collectively mention Plato twelve times, offered the deep insight that, “while it may not be the end of the world, it is certainly the end of a world.” In n+1 the meditations were more self-analytical. “Being sick means being frail, a condition that I despise and also revel in,” wrote one contributor. “Some days, the thought I might die here during this pandemic fills me with bemusement, some days with dread,” wrote another. “Some days I’ve thought that my purpose in coming here was to die… Perhaps I’ve come here not as a terminally vague, indecisive Hamlet-quoting autofictionist, but as a witness, a kind of Horatio.”

Others interrogated their privilege—but it’s hard to tell which brand of self-absorption is more ludicrous. Yet another New Yorker contributor worried “on a semiotic level” that her mask might mark her as a “scared, entitled, white woman.” This predicament grew existential: “I don’t know how to make a case for my presence in this world at all.”

Many of the intellectuals suffered from an affliction nearly as contagious as Covid-19. “I can hardly read” (n+1), “I have no energy for extended reading” (The Point), “On Twitter, people said they couldn’t read, either” (The Point), “At first I couldn’t read” (The Point) “I can hardly concentrate in daytime. At night, I read” (The New York Times Magazine), “I try to read, but my eyes blur. I tell myself this is OK” (n+1). At the outset of the pandemic, New York’s sole staffed literary critic picked up The Magic Mountain and declared, “After 200 pages, I was like, Fuck this. Nobody wants to read about some dude sweating out a possibly metaphorical case of tuberculosis in a fur-lined sleeping bag. Now is the time for books that go down like rice pudding.” Should even the pudding-books prove too taxing, though, the—again—literary critic offered an alternative suggestion: “Create a folder on your phone and fill it with soothing images to consult when anxiety seizes you. (My folder is titled ‘Soothing Images.’) Populate it with pics of baby elephants, shady grottoes, buttered toast—whatever reduces your palpitations.”

By now, the quarantine diary has calcified into a genre. Jon Baskin, founder of The Point, led a talk at The New School called “Quarantine Journals: Publishing During a Pandemic.” n+1 rushed to compile its diaries into a book (tagline: “an urgent collection of essays”). Its price ($1.99) is almost an admission of guilt. At least one Times book critic thought the trend worthy of a summary-essay: “Such accounts—many banal, at best—turn interesting, even significant, when read together and regarded as a wave of testimony.” In our view, it’s less a wave of testimony than a testament to the literary world’s capacity for navel-gazing.

While the commentariat romanticized their comfortable loneliness and canceled Alison Roman, anger roiled beneath the surface. Its sudden eruption might have jolted the online literary world out of its self-absorption—and for a little while, it did.

The gruesome video of George Floyd’s murder triggered riots, and the images of those riots (a precinct cinematically in flames) sent thousands of young people into the streets. Each day brought new footage of police brutality at protests against police brutality, which only increased the determination of the next day’s protestors. Those of us who waste too much time on Twitter were briefly reminded of the socially useful capacities of the platform: for a week or so, it was all video, all the time—the kinds of videos that allow for new gatherings to spring up organically across the country.

And then, the conversation took a turn: stories of police brutality were replaced by objections to the inflammatory op-ed Tom Cotton published in the New York Times with the headline “Send In the Troops.” A staff revolt at the Times precipitated scores of analyses of the Cotton op-ed and cancel culture, the Cotton op-ed and the changing ideology of news organizations, the Cotton op-ed and Twitter. The Times published eight op-eds on the op-ed itself. The New Republic devoted four articles to it. Matt Taibbi folded it into his screed on the left’s transformation into “a cowardly mob of upper-class social media addicts, Twitter Robespierres,” which engendered yet another cycle of takes on free speech and censorship.

Not two weeks out from the protests’ inciting events, the media had cannibalized the story. The outrage was less directed at the fact that a sitting Senator wanted to commit war crimes against American citizens than at the process by which an editor at The New York Times had solicited and published his opinion.

Soon, the backlash extended beyond the Times and took aim at racism across New York’s elite media organizations, beginning with an outpouring of horror stories from Condé Nast staffers and freelancers. Leaders at Bon Appétit, Refinery29, Man Repeller, and others stepped down or “stepped back.” As the writer Tobi Haslett tweeted, “the end of the riots means that everyone has devolved to interrogating racism within their hermetically sealed professional community—inevitably.” In the streets, masses of young people were earnestly calling for abolition and shouting about the school-to-prison pipeline. Meanwhile, on Twitter, the professional media was comparing salaries and book advances.

This reckoning is well-deserved, but it is a sign of inner rot that in watershed political and cultural moments the media can only double in on itself as demands for political or legislative change give way to stories about badly behaved editors. The existing publications are so riven with corruption and inequity that—at the major inflection points for societal change since Trump’s election—reporters, writers, and thinkers have their attention divided by internal fights over their own basic working conditions.

For the past few years, the culture industry has been engaged in a strange moral and rhetorical project: retroactively applying standards born out of a reaction to Trump to behavior and art that preceded his election. From the start, there was something disingenuous about the way #MeToo was treated in the media, which largely feigned shock at the discovery of abhorrent behavior that had been hiding in plain sight.

None of the offenses that suddenly became fireable were well-hidden because they weren’t considered worth hiding. There are jokes about Harvey Weinstein, serial sexual harasser, on 30 Rock. Charlie Rose, whose employees referred to his practice of flashing female assistants as “the shower trick,” was introduced at a 2014 fundraiser with the quip, “We’re all here because with Charlie Rose, one woman is never enough.” The sexualized atmosphere Lorin Stein cultivated as editor of The Paris Review was no secret to anyone who read the The New York Times article announcing his appointment: it called him a “sex symbol” and a “serial dater,” a man perfectly suited to a role in which “Bacchanalian nights are practically inscribed in the job description.”

Just a few weeks after the Weinstein revelations, the media world shifted its focus to the Shitty Media Men list, a document in which anonymous accusations against lit-world figures ranged from inappropriate comments to rape and assault. The list prompted essay after essay—in The New York Times, New York Magazine, Harper’s, The New Yorker, etc—in which men and organizations are alternately attacked and defended for the culture of abuse from which they profited. Many of the purported disquisitions on the state of sex and gender in American culture at large amounted to gossip about a couple of thinly anonymized men whose descriptions you’d be able to recognize only if you were an industry insider. For the rest of us, the analysis was largely impenetrable. It was easy to assume the writers were talking about dozens of men, even as they referred over and over to the same few.

The Shitty Media Men list was no more a revelation to New York media than the Weinstein accusations were to Hollywood—the gender and sexual dynamics of literary organizations were manifestly regressive. As Wesley Yang wrote, in New York’s pre-Trump literary scene, “most everyone who could do the inappropriate was doing it.”

In the end, a handful of editors, including Stein, were made into public examples, allowing the power structure that had enabled them to remain largely intact. The editors who were promoted to replace them may have thought twice about hitting on their staffs, but still found plenty of racist, classist, and indiscriminately cruel ways to take advantage of the power they wielded. Those who weren’t actively abusing their assistants didn’t need to—the system would simply do it for them via unlivable wages, endless apprenticeships, and entrenched toxic holdovers from a more “genteel” era in publishing.

At the time, Masha Gessen wrote, “Perhaps the swift execution of entertainment and media careers can be seen as an attempt to build a wall of sorts—a clear division between people who felt that the ‘Access Hollywood’ recording rendered Trump unfit for office and those who did not.” #MeToo was an attempt to distance the centers of liberal cultural production from Trump and Trumpian behavior. It was not a form of political action, but an expression of political impotence. As Mary Gaitskill’s #MeTooed character remarks in a short story explicitly about the movement, “They can’t strike at the king, so they go for the jester.”

Despite the embarrassment of its 2016 campaign coverage, the media bounced back with a new sense of self-importance. Subscribing to The New York Times was pitched as a patriotic sacrifice in support of the heroes who would rescue our republic. From the breathless Russiagate reporting and each new installment of the Mueller saga to the #MeToo crusade, liberals became enchanted by the idea that we were always just one revelation away from making the bad man in the White House go away. Failing that, we would somehow thwart the pussy-grabber-in-chief by publishing exposés about the most prominent abusers in Hollywood and Manhattan—hardly a scalable model of accountability.

Somehow, we haven’t been able to write or report our way out of the problems that led to Trump, just as “reflecting on our privilege” won’t undo structural racism, and #MeTooing more men won’t get us to gender equality. In the Trump era, liberal culture has been all politics, all the time. Contemporary girlboss feminism is ahistorically espoused in historical dramas. Novels end with plot twists intended to teach lessons about toxic masculinity. Culture producers seem to be suffering from the collective delusion that what’s needed is a base of perfect liberal consumers with cleansed souls and spotless psyches—rather than radical legislative and political challenges to the actual mechanisms of power. In this context, the media’s impulse to turn inward feels like a retreat, an abdication of responsibility for fixing anything outside itself.

All this should have provided a perfect opportunity for the little magazines to distinguish themselves—to lay claim to a mass of bored and disenchanted readers by offering an alternative to the mainstream liberal media.

There are plenty of little magazines, each with its own nominally distinct flavor. But they all draw from the same stable of freelancers, write around the same media-Twitter shibboleths, and seem increasingly out of touch with the current intellectual and affective landscape—one in which a new crop of heterodox, irreverent, and sometimes minimally fact-checked leftist podcasts have been earning millions of dollars in subscription fees.

To ignore or dismiss these shows as trivial corollaries to publications, or merely a passing fad, is to preclude the possibility that they are articulating something absent from the rest of the conversation, something reflective of real political attitudes. In an age of screenshots and cherry-picked quotes, podcasts are largely immune: it’s difficult to take an audio clip out of context and cancel it; you’d have to listen all the way through and transcribe. Maybe this is why podcasts tend to be freer than magazine articles—looser with facts and opinions. But it’s also partly because their hosts tend not to take themselves too seriously.

The little magazines, by contrast, suffer from a congenital addiction to seriousness. n+1 was founded to “defend the possibility of seriousness.” Jacobin’s founders sought an antidote to “a general lack of ideas, of taking ideas really seriously.” Not to be outdone, The Point sought to remedy the “intellectual poverty” of contemporary discourse with “serious and seriously entertaining essays.” The galvanizing experience of Occupy, and then the overt ridiculousness of the Trump administration, only rendered the seriousness seriouser. But it emerged in response to the reflexive jingoism and general idiocy of the Bush years, when the founding editors of n+1 sought to bring back the tone and tenor of Partisan Review, that ur-magazine of the literary-intellectual set.

In 1948, a soon-to-be forgotten novelist wrote in his journal that all the young men around him were writing novels and founding little magazines, each hoping to be the first to account for “the drift of the times.” There’s a certain nostalgic appeal to what those young men (together with a few under-appreciated female luminaries) built in the forties and fifties. Yet the atmosphere of their golden era of little magazines—in which glamor went hand-in-hand with an overinflated sense of self-importance—no longer needs reviving.

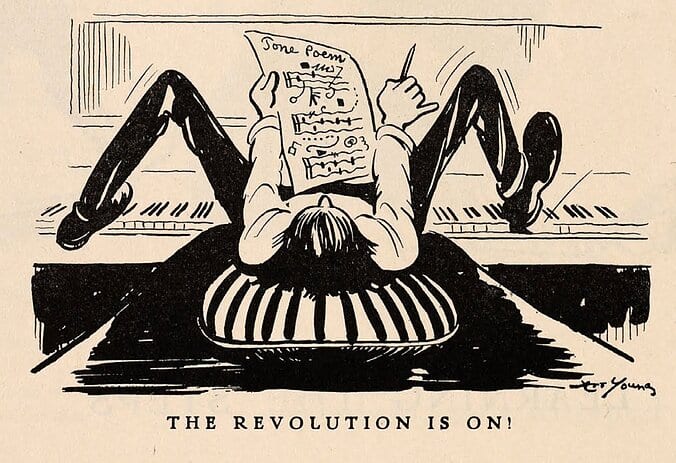

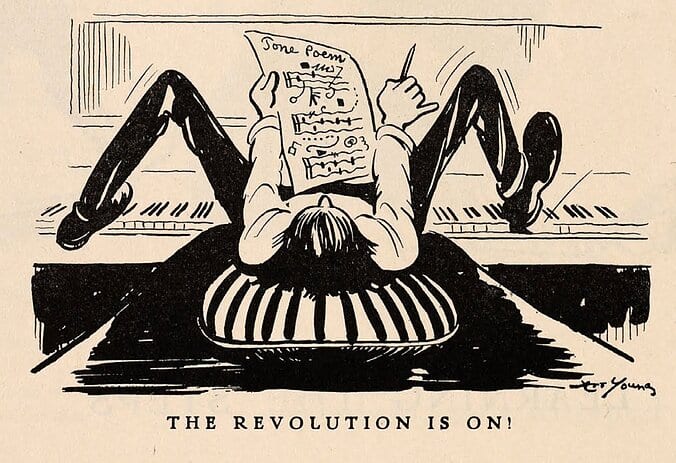

We’d like to take a longer tiger’s leap, turning instead to the modernist monthly The Masses (1911-1917). Born out of the bohemian socialism and forward-thinking experimentalism that flowered in pre-World War I Greenwich Village, The Masses was as committed to the revolution as it was to humor, playfulness, self-ironizing, and avant-garde literature and art.

Where the midcentury magazines dripped testosterone, played host to mammoth-sized egos, and enjoyed CIA funding or independently bought into the Cold War liberal consensus, The Masses was feminist, socialist, anti-war. Although its name belied its true readership (and editorial makeup), The Masses published still-apt cartoons and broadsides on everything from labor organizing to Wall Street and American imperialism.

Its 1913 missive describing the rift between the Progressive Party and the Socialist Party could have been written about the Sanders-Warren schism in the 2020 primary: “Essentially they represent the enlightened self-interest of capitalists. We represent the enlightened self-interest of the workers, and the fight goes on.”

The magazine went all in for Eugene Debs and followed international labor fights obsessively. It declared that American prisons were “conceived in barbarity and maintained through the callous indifference of those who frame and execute our laws” and demanded that “the entire system be replaced.” It identified anti-Black racism in “widespread political disenfranchisement, and loss of civil rights” and insisted on an immediate fix. Controversially for leftists at the time, it advocated suffrage and birth control, defending Margaret Sanger when she was arrested under obscenity laws. “Sex equality is a question by itself,” wrote editor Max Eastman in one of his first essays after taking over the magazine in 1912. “Progressivism does not include it. Socialism does not include it.”

The Masses famously called itself “A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable.” We think there’s an audience now for this kind of magazine: one in which socialism and feminism don’t entail moralizing; in which political wars are not fought on cultural battlefields; in which an essay isn’t an excuse for self-indulgence; in which there’s more to the media than endless recursive analysis of the media.

So, with the preceding thirty-five hundred words of recursive media analysis, we’d like to introduce the first issue of The Drift. In it, we tell you about the shady biotech company that’s capitalized on the coronavirus vaccine arms race, and the backstory of pandemic-era Social Darwinism. We dissect the vestiges of racism in The New Yorker’s “Goings On About Town” section, the liberal interventionism represented by Samantha Power, and the science of global pork farming. We consider the change in national consciousness due to Black Lives Matter, and follow the current wave of protests around the country and the world.

You’ll find analysis of the surprising tactic that won the Harvard graduate student union its recent contract, as well as the way that organizing language has infiltrated queer nightlife. To take the long view of the present political and economic situation, we interviewed the theorist Wendy Brown, and for a diversion, we offer a fictional escape to an Italian seaside town. Our poetry takes aim at globalized corporate-speak; in a series of extremely abbreviated reviews, we take aim at everything from nineteenth century novels to the online anti-natalist community.

In the mode of The Masses, we aim to engage with serious ideas without taking ourselves too seriously. The Drift will be an (aspirationally) quarterly magazine of culture, politics, literature, and ideas. It will publish fiction, poetry, and essays that challenge the established thinking on any number of subjects.

Most of all, we’re committed to offering a forum for young people who haven’t yet been absorbed into the media hivemind, and don’t feel hemmed in by the boundaries of the existing discourse. These are times in which the world needs fresh voices: we’re certain that there’s more to say, and more fun to be had saying it. In this moment of upheaval, of outrage both misplaced and righteous, of loneliness, and of alienation, we hope to provide an outlet for new writers and a new alternative for readers—to try and capture, with no outdated pretensions, the drift of the times.

—Kiara Barrow + Rebecca Panovka