Illustration by John Kazior

Illustration by John Kazior

Over the course of a week at the end of 2020, the air tens of thousands of feet above the North Pole heated 100 degrees in what’s known as a sudden stratospheric warming event. This phenomenon, which scientists predict could become more common with climate change, wobbled the great atmospheric turntable of the jetstream, sending waves of Arctic air towards the U.S. Two months later, Winter Storm Uri arrived, blanketing 73 percent of the lower 48 in snow — the highest level since NOAA began tracking the figure in 2011 — and wrenching Texas into pre-industrial darkness. The state has long prided itself on the so-called Texas Miracle: low regulation, small government, cheap living, economic growth. When Uri descended, dropping record snowfall on cities like Austin, Abilene, and San Angelo, it was history colliding at two speeds — a landmark storm meeting a much longer systemic failure of imagination and political will.

Uri struck a brittle and vaguely libertarian electric system. Weather forecasters downplayed climate change in their predictions. Producers hadn’t winterized equipment for fear of passing on costs to consumers. Plants weren’t incentivized to hold power in reserve. The Lone Star State is electrically isolated, unconnected to the two federal super-grids serving the eastern and western halves of the country. The Texas power supply came within minutes of total collapse. At least a hundred people died during the storm, many of hypothermia, many in the Black and brown neighborhoods where the blackouts were the worst. Some burned furniture to keep warm. Consumers were left with four- and five-digit electric bills, and the state incurred $90 billion of damage. Meanwhile, Governor Greg Abbott blamed Texas’s windmills, taking the opportunity to stoke fears about the Green New Deal — even though Texas mostly runs on fossil fuels, and windmills actually out-produced these energy sources throughout the crisis.

Soon after, America’s favorite billionaires stepped in. Bill Gates was on Bloomberg defending renewables and touting Breakthrough Energy Ventures, his for-profit energy technology investment firm. Elon Musk, who recently relocated to Texas and is constructing a massive power storage facility near Houston, was on Twitter trolling the state’s grid operator. Warren Buffet offered to build an $8.3 billion cluster of natural gas plants to shore up the state’s energy reserves — in exchange, of course, for a guaranteed 9.3 percent rate of return on his investment paid out from extra fees on consumer utility bills.

But no billionaire sees Texas as a bigger proving ground for high-tech world-saving than Jeff Bezos. The Amazon tycoon attended elementary and middle school in Houston, where his adoptive father was a petroleum engineer for Exxon. As a teen, Bezos spent summers among the mesquite trees on the 25,000-acre “Lazy G” Ranch in Cotulla, Texas, reading sci-fi books from the local library. It belonged to his grandparents, Lawrence Preston Gise and Mattie Louise Strait, both of whom cast their influence across time and space on a monumental scale, just like their grandson. Gise worked on ballistic missile defense and space technology at the Defense Department in the ’50s and ’60s, and Strait comes from a line of Texas ranchers dating back to John Joseph Strait, a Confederate soldier.

In February, Bezos announced a homecoming. Later this year, he’ll be stepping down as Amazon CEO and will focus on his projects fighting climate change and promoting space travel, both of which have deep roots in Texas. During Bezos’s tenure as CEO, Amazon built a 100-plus turbine wind farm in Scurry, a small town outside Dallas, as part of its company-wide carbon neutrality push. Bezos also owns 300,000 acres near the West Texas railroad town of Van Horn, home to the projects that Bezos conceives as his ultimate endgame, for himself and for humanity. The expanse encompasses a launch site for his space colonization venture, Blue Origin. It also hosts an even more ambitious and idiosyncratic project: the 10,000-year Clock of the Long Now.

Bezos has maintained a disturbingly consistent lifelong plan for getting humans into space to escape an insufficient Earth. In his 1982 high school valedictorian speech, he quoted from Star Trek’s opening (“Space: the final frontier”) and laid out his plan to secure the future of the human race by moving us all onto a giant space station and turning the Earth into a wildlife preserve. “He believed that we, as a species, had to explore space because this was a very fragile world, and we weren’t taking good enough care of it,” a former girlfriend, Ursula Werner, told Robert Spector in his 2000 biography of Bezos, Amazon.com: Get Big Fast. “He was not so focused on the ecology side — that we need to worry about our Earth more — but more about taking a long-term view of the Earth as a finite place to live.” Bezos’s plan hasn’t changed much since 1982, but the contents of his bank account have. Speaking with journalists in the ‘90s, Werner put a finer point on it: “The reason he’s earning so much money is to get to outer space,” she said. That money is now funding Blue Origin in Texas.

To drive his point home, Bezos is working on another ultra-long-term project meant to vault humanity beyond Earth’s immediate constraints. Together with the Long Now Foundation, a group of wealthy Silicon Valley eccentrics, he has spent 16 years and around $42 million of his fortune installing a clock that will tick for 10,000 years 500 feet deep inside the nearby Sierra Diablo Mountains. The stated goal is to encourage people to consider their relationship to the timescales of nature and civilization; with this profound historical vision, the logic goes, the human race will be inspired to undertake revolutionary changes that could only occur across multiple generations. Every empire has its capital, and every ideology has its temple. For Bezos, that’s Van Horn. “If people pay attention to the clock,” Bezos told Wired in 2018, “they’ll do more things like Blue Origin.”

Bezos made his fortune as a master of efficiency, seizing every marginal dollar of profit that could be wrung out of economies of scale, military-grade logistics, reams of data, and a vast network of employees and contractors pushed to the limits of productivity. Blue Origin and the Long Now clock operate on an opposing logic; both are deeply, existentially inefficient. Trying to save the world as the richest man in it comes with inescapable contradictions — money-making versus the common good, ambition versus delusion — that even someone as cunning and ambitious as Bezos hasn’t figured out a way to overcome.

Last fall I drove from Northern California to West Texas to see just how a billionaire retail magnate plans to save the world from climate change with rockets and a giant clock. Once there, I thought, I’d finally understand what Bezos was trying to say with Long Now and Blue Origin, and, more broadly, what these endeavors suggest about the society that the billionaires of our time are trying to build for the future. But I didn’t find anything. After driving for three straight days through wildfire smoke, quarantine-quiet desert towns, and Border Control checkpoints, the closest I could manage to get to the clock was peeking past the gate to Bezos’s ranch. Months before, my entreaties for a private tour were rejected. The 10,000-year clock isn’t yet open to the public either. Even the cattle inside the fence didn’t like outsiders; they bolted at the sight of me. There are a few prototypes of the clock to see — two in San Francisco and one in London — and another clock planned for a remote mountain top in Nevada, but for all practical purposes, this project still exists mostly as a mental exercise for rich inventors.

As it stands, this portal to the utopian future yields nothing more than a bombastic reminder of the inequalities of the present, of who stands on which side of the 300,000-acre fence. But leaning on a parked car outside the gates may be the perfect way to experience the Bezos agenda: at a far remove. The clocks and the rockets are spectacular monuments to nothing, built by people who have little to suggest about improving the future beyond their own centrality in it, and even less to say about the present world order of scarcity and precarity they helped create.

If our contemporary tech billionaires have taught us anything, it’s that blind trust in technology makes for a dreadful kind of progress. Silicon Valley tech makes its creators wealthy and influential, and massive wealth and influence convince people to trust the wealthy and influential to tackle equally massive societal problems. Those with the most must be the best. Ultimately, the solutions dreamed up by Silicon Valley have a way of making founders still more wealthy and more influential. This lopsided accumulation of resources further degrades the social and environmental fabric, and the cycle repeats. In the hazy fog of half-progress, half-plunder, the rest of us are left waiting for the titans of Silicon Valley to save us.

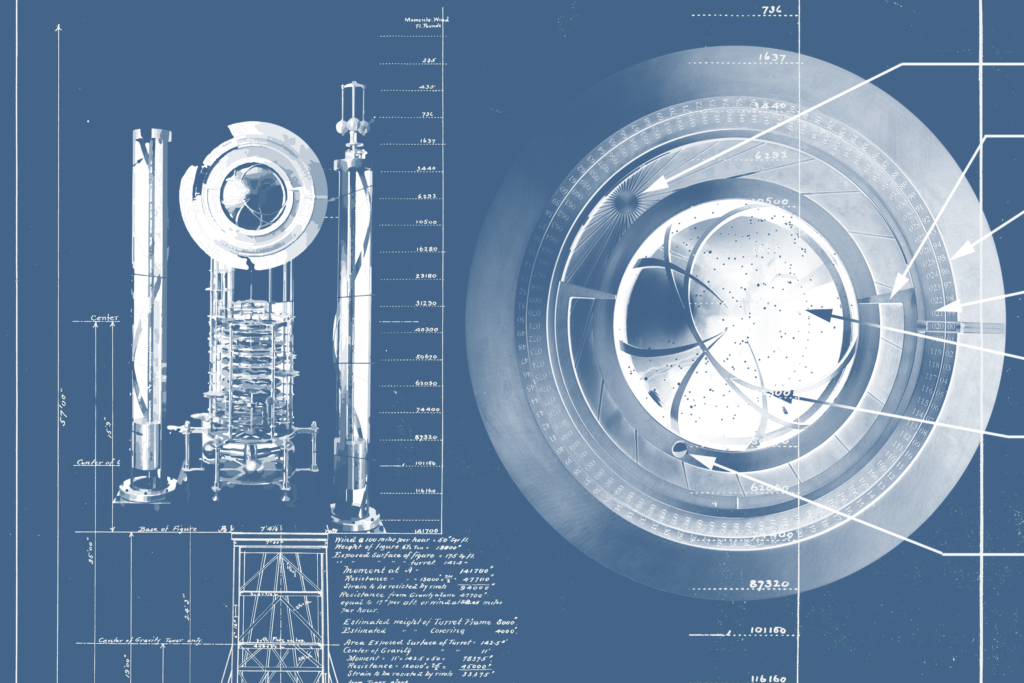

In a mechanical sense, the clock is perfect: efficient, self-sustaining, awe-inspiring. No one else has ever made anything like it. “To see the Clock you need to start at dawn, like any pilgrimage,” Kevin Kelly, a founding editor of Wired magazine and a Long Now board member once wrote. Visitors hike 1500 feet up a bare mountainside until they reach a hidden door in a rock face leading to an airlock. Once inside, a tunnel leads into a 500-foot cylindrical cavern, which houses a robotically cut stone staircase wrapping around the clock, a steampunk geothermal marvel of huge interlocking gears roughly 200 feet tall.

The clock can power itself and keep time for millennia without human intervention. Pushing a capstan winds the clock, powering a massive weight and gear mechanism made of stainless steel, ceramic, and titanium, which strikes one of 3.5 million unique chimes at noon. At the top of the clock, the date and time are displayed on an eight-foot disk that mechanically maps the changing positions of the stars since the last visit.

The entire mechanism keeps its own time internally, gathering energy from sunlight beamed in through a sapphire glass cupola above its chamber, which transfers energy to a series of metal rods and gears that ensure the clock remains set to solar noon. A six-foot-long, 300-pound titanium pendulum marks the rhythm. At the intervals of 1, 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 years, hidden chambers inside the clock open up to reveal DaVincian gizmos marking each milestone.

The first prototype of the clock was completed just before Y2K, on December 31st (“01999,” in the multi-millennial argot of the Long Now Foundation). It now sits on loan in the London Science Museum — a fitting home, since London, a longtime seat of empire, is where the clock’s intellectual lineage began.

In 1965, Royal Dutch Shell’s London office began a program called Long-Term Studies — the “futures division,” for short. The idea wasn’t to predict any one future, but to prepare for its divergent possibilities. This approach, now popular in business strategy, is known as scenario planning. It helped Shell battle Exxon, anticipate the decline of the Soviet Union, and correctly predict (in 1998) that the public would freak out when it eventually learned that oil companies knew about climate change decades before they let on.

In 1988, a group of futures division alums took their talents to California and turned the scenario planning process into a combination think tank/consulting firm. They formed the Global Business Network (GBN), a multidisciplinary salon of far-out brainiacs. Like any group of esoteric rich guys, they fancied themselves “heretics” doling out dangerous truths. But many GBN members were already well established in their respective fields: the group included, among others, musicians Brian Eno and Peter Gabriel, Pulitzer prize-winning oil historian and energy executive Daniel Yergin, Wired magazine founding editor Kevin Kelly, supercomputing pioneer Danny Hillis, and political scientist Francis Fukuyama (of “end of history” fame). Its roster of clients and funders over the years was even more powerful, featuring representatives from big banking (Deutsche, Standard Chartered, American Express), big auto (Nissan, Toyota, Fiat, Volvo), big tech (IBM, Nokia, Microsoft), the Generals (Electric, Mills, Motors, the Joint Chiefs of Staff), and of course the oil companies (Shell, Exxon, Petrobras).

GBN’s most intriguing member was the publishing maven Stewart Brand, a man who seems to have carried the whole counterculture on his back. He was a friend of author Ken Kesey and lived communally at Ken’s homes as part of the acid-dropping, schoolbus-driving “Merry Pranksters,” famously profiled in Tom Wolfe’s book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Brand assisted with the Bay Area acid experiments and computer demos in the 1960s that helped inspire a generation of hippies, technologists, and hippie technologists. In 1966, he lobbied NASA to release some of the first pictures of the entire Earth. Two years later, his instincts about the power of these images proved correct. The photos “Earthrise” and “Blue Marble,” taken from the moon’s surface by Apollo 8 astronauts, became some of the most widely disseminated images in human history. Some credit these pictures with galvanizing the nascent environmental movement.

In 1968, Brand founded the Whole Earth Catalog, a cult magazine that mixed practical advice for people looking to drop out of the system (how to fix VW buses or build communal homes) with the rugged individualism at the heart of their utopian projects. Whole Earth championed Ayn Rand’s libertarian novel Atlas Shrugged, as well as the whiz-bang charm of the mid-century inventor and futurist Buckminster Fuller, who popularized the use of geodesic domes in architecture. Fuller’s legacy as an inventor turned out to be mostly aesthetic, but his public persona was a model for generations of self-styled futurists and revolutionaries. He envisioned the new figure of the Comprehensive Designer, “an emerging synthesis of artist, inventor, mechanic, objective economist and evolutionary strategist.” The seekers of the West Coast took notice.

Brand and his readers saw themselves this way, as the creators of their own eclectic universes, able to achieve new forms of prosperity totally outside the normal boundaries of American life. It was a deeply appealing idea to the middle-class white kids at the core of the hippie movement, who sought societal autonomy they mostly already had. It was also an uncanny precursor to the way tech founders style themselves today, as polymath altruistic businessmen. Embodying this master of the universe spirit, the mission statement on Whole Earth’s first issue read, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.” Its 1971 run sold over a million copies. Steve Jobs was a huge fan.

Despite its symbiosis with the global establishment, GBN was something of a utopian dream. Writer Joel Garreau, a GBN member, wrote in a 1994 Wired article that the consultancy aimed to replicate the prophetic ways of Shell’s Long-Term Studies department, “not just for one company, but for the world.” The members of GBN lived by the idea that a group of cool and forward-thinking (and rich) people could tackle any and every problem.

It might seem like a strange ideological marriage between the free spirits and the free markets, but the Bay Area’s infatuation with futuristic computing technology created a unique hybrid politics, as theorists Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron argued in their 1995 essay “The Californian Ideology.” Everyone from anarchists and hippies to executives and right-wingers found something to like in the wired future. For some, the appeal was that computers would create a “global village” of new spaces in which people could connect and share ideas directly, without traditional, repressive hierarchies. For others, the free-flowing internet was the ideal place for perfecting capitalism, where small, independent producers could share the market with the big corporate and military interests driving the development of computer technology. “This amalgamation of opposites has been achieved through a profound faith in the emancipatory potential of the new informational technologies,” Barbrook and Cameron write. “In the digital utopia, everybody will be both hip and rich.”

It was an intoxicating vision of an ideologically, environmentally, economically frictionless future. It lulled Silicon Valley into thinking its own dynamism could save the world. And it rested on an assumption that after the Cold War, the powers that had spent the previous few centuries carving up the world while polluting it to near death would begin wielding alliances, trade, and technology neutrally. Capitalists and colonizers would somehow welcome former colonies and former communist nations into the sanctums of prosperity and liberalism they’d spent decades fortifying at gunpoint. Globalization and information technology would split the atom of societal inefficiency and bombard all who came close with progress. Three years before the dot-com crash and five years after the Kyoto Protocol, a 1997 Wired cover story, written by former Shell futures division chief, Long Now board member, and GBN co-founder Peter Schwartz boasted, “We’re facing 25 years of prosperity, freedom and a better environment for the whole world. You got a problem with that?”

As the millennium approached, perhaps owing to their eclectic circle of friends, some of the brain geniuses at GBN started looking beyond Silicon Valley’s pure techno-optimism and wrestling with a different sort of Next Big Thing: our looming ecological collapse. It began to dawn on members like Hillis, Brand, and Kelly that the promised age of a global, prosperous digital commune was not coming to pass. The threat of climate change and irreversible ecosystem destruction was fast arriving, and so, they thought, was The Singularity, the moment when AI and other technologies would eclipse and ultimately overpower human intelligence.

“It feels like something big is about to happen: graphs show us the yearly growth of populations, atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, Net addresses, and Mbytes per dollar,” Hillis wrote in the 1995 Wired article where he first proposed the 10,000-year clock. “They all soar up to form an asymptote just beyond the turn of the century: The Singularity. The end of everything we know. The beginning of something we may never understand.” What was needed, he reasoned, was an enduring symbol to orient people in time, given all the dizzying changes taking place around them. “I plant my acorns knowing that I will never live to harvest the oaks,” he continued.

Hillis and others believed that a 10,000-year clock would inspire people to dream up the large-scale solutions that would be necessary to ensure human survival. “If you have a Clock ticking for 10,000 years, what kinds of generational-scale questions and projects will it suggest?” Kelly, the Wired founder, wrote in his own essay about the clock. “If a Clock can keep going for ten millennia, shouldn’t we make sure our civilization does as well?”

In 1996, Hillis, Brand, and Kelly and others established the Long Now Foundation to advance the clock project. The group hosted salons with high-profile thinkers and archived both human languages and archaic digital file formats. Running through each project was a conviction that the culture at large needed to focus intently on preserving what we have and preparing for the vast unknowns of the future.

The Long Now Foundation’s guiding idea is “deep time,” a concept often traced back to the work of 18th century Scottish polymath James Hutton. In his 1788 essay Theory of the Earth, Hutton, who made a fortune in the smelling salts business, introduced to Western science the idea that geological features were ancient, formed through observable, millenia-long cycles of development. (Indigenous peoples the world over have lived throughout history by various understandings of both day-and-month and epochal time for thousands of years.) Hutton, for his part, arrived at his thinking by closely observing how erosion on his farm over decades reshaped the landscape and studying geological features like Scotland’s Siccar Point, an ancient sandstone and greywacke formation. These features suggested to Hutton that the Earth’s history was much longer than the few millennia the Bible allowed, with “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.”

Hutton’s reframing of geological time, as eco-critic David Farrier has argued, was a “Copernican” shift that put natural processes above gods and humans as the drivers and measures of history. Heliocentrism displaced human beings from the center of the celestial story, but geological time underscored our dramatic insignificance. Everything around us, the very ground we walked upon, moved at a speed totally indifferent to human civilization. Nearly two hundred years after Hutton advanced his theory, in a 1980 New Yorker story on North American geography, the writer John McPhee coined the phrase that gave this vision of humanity’s place in the story of Earth a name: “deep time.” He used the term when describing the struggle to capture just how old something like the Appalachian mountain range really is. “Numbers do not seem to work well with regard to deep time,” he argued “Any number above a couple of thousand years — fifty thousand, fifty million — will with nearly equal effect awe the imagination to the point of paralysis.”

Deep time, as a concept, never broke through into the political world in the way Darwinism did. It survives as a guiding idea for a few nature writers and a useful teaching aid in geology classes. Long Now’s innovation, and perhaps its great mistake, was bringing the humbling ethos of deep time beyond the slow, analytical world of intellectuals and scientists into Silicon Valley, where speed and ego are the primary operating systems. Startups rise and fall in a matter of months, making and wasting millions of dollars. Until 2014, Facebook’s internal motto was “move fast and break things.”

But the clock, Long Now believed, was a symbol so powerful it could convince people to see beyond this limited horizon of self-enrichment toward a more profound kind of success, of the human race across the planet in deep time. “Accepting responsibility for the health of the whole planet, we are gradually realizing, also means responsibility for the whole future,” Brand explained in his 2000 book The Clock of The Long Now. To accomplish this, like any great Silicon Valley creation, the big ticker had to dazzle, to become a “mechanism and a myth,” as Brand puts it. It also had to be useless.

Nothing practical could become the sort of dominating worldwide cultural and historical totem that humanity supposedly needed. Brand writes that the chief rivals for the clock, in terms of symbolic heft, were the A-bomb mushroom cloud and the pyramids of Giza. “It has to match their vaulting ambition,” Brand wrote of these instantly comprehensible icons. “The pyramids also demonstrate the power of folly. You can’t argue with them because they’re not rational.”

To actually complete such a project, Long Now needed someone with a very particular combination of contradictory attributes: a person as wealthy and grandiose as a pharaoh, who nonetheless worried about humanity’s excessive footprint on Earth. They found the ideal partner in Jeff Bezos.

By the early 2000s, after taking Amazon public, Bezos was a billionaire and could finally expand his family’s fingerprint on the Earth and in the heavens. Now the 25th biggest landholder in the U.S., Bezos has spent years snapping up Texas parcels under a series of shell companies — James Cook L.P., Jolliet Holdings, Coronado Ventures, William Clark Limited Partnership, and Cabot Enterprises — named for famous explorers and conquerors, linked to a holding company called Zefram LLC, after a Star Trek character who invents a “warp drive” that powers faster-than-light space travel. His Van Horn ranch sits on land where the US Army carried out some of its final battles to destroy and dispossess the Apache ahead of the arrival of the railroad. Now it is dedicated once again to pushing the frontier forward at all costs.

Blue Origin has spent the last two decades pioneering reusable rockets for more sustainable space travel, a first step towards fuller space colonization. The mission of Blue Origin is little different from what a teen Bezos had imagined back in high school, only now Bezos fuels it with an estimated $1 billion of his own money each year. Faced with deep time-sized threats to human survival, Blue Origin is an escape hatch.

“If we move out into the solar system, for all practical purposes, we’d have unlimited resources,” Bezos told an audience at the event debuting Blue Origin’s lunar landing craft in 2019. Resources, however, are already somewhat limitless in this case: NASA awarded Blue Origin a $579 million contract to build a prototype as part of a three-way competition to see which company would win a final, $2.9 billion contract to support the agency’s next moon mission. (NASA ultimately selected a rivalling bid from Elon Musk’s SpaceX, a decision Blue Origin is currently challenging.) In space, Bezos promised at the unveiling, humans wouldn’t have to worry about the decidedly non-free market future of “rationing” on Earth. Those still on this planet would tap into the infinite energy of the solar system, and those in space would live in a series of floating colonies so abundant they’d produce “1000 Mozarts and 1000 Einsteins.” It was a future, he once explained to an interviewer, that would recreate the boundless optimism of the past, where natural resources were considered inexhaustible. “I don’t want my great-grandchildren’s great-grandchildren to live in a civilization of stasis,” he once told an interviewer. “We all enjoy a dynamic civilization of growth and change. Let’s think about what powers that. We are not really energy-constrained,” he said. We are, of course, energy-constrained, though material boundaries don’t factor much into the Bezos agenda.

Bezos’s strain of thinking about space colonization is a descendant of both the “Manifest Destiny” myth of the nineteenth century, imagining a righteous future of plenty to be conquered by the chosen on a distant frontier, and those who retrofitted this idea a century later onto the space race. In the 1970s, Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill began arguing that, given the depletion of world resources, colonizing space in a series of self-reproducing space stations was our best hope, each installation tapping into unlimited solar energy to build the next link in the chain of continued human expansion. Earth, meanwhile, would heal “from the ravages of the industrial revolution,” he once wrote. “The human race stands now on the threshold of a new frontier, whose richness surpasses a thousand fold that of the new western world of five hundred years ago,” O’Neill said in 1975, in remarks published by a funky magazine editor in California named Stewart Brand. “That frontier can be exploited for all of humanity.” O’Neil briefed Congress on his plan, and NASA funded a conference to help flesh out the finer engineering details.

Not everyone was enamored, of course. Writer Wendell Berry called the idea of moving humanity onto space stations “an ideal solution to the moral dilemma of all those in this society who cannot face the necessities of meaningful change.” What’s more, the fact that space travel was only possible for wealthy nations meant the same imperial powers currently hoarding and spoiling Earth’s resources would do the same with any future rewards in space. “It is superbly attuned to the wishes of the corporation executives, bureaucrats, militarists, political operators, and scientific experts who are the chief beneficiaries of the forces that have produced our crisis,” he wrote. Many shared Berry’s skepticism, and the idea of space colonization fell out of fashion as the Cold War subsided, but the idea did seem to stick with Jeff Bezos, who was one of O’Neill’s students at Princeton.

Two decades after his valedictorian speech, Bezos was rich enough to make O’Neill’s dream a reality. And right as he was founding Blue Origin, he began partnering with a group of intellectuals who were equally interested in using moonshot technology to save humanity. In 2003, Bezos provided the seed money for Long Bets, a Long Now Foundation program the organization dubbed “the arena for accountable predictions,” where thinkers made public cash bets on the future of society as means to “improve long-term thinking.” Hillis was a good friend of Bezos’s, as well as an early partner in Blue Origin. In 2005, Bezos made the longest bet of his life and committed to building the 10,000-year clock on his ranch. Together, Bezos and Long Now spent the next two decades solving the engineering challenges that came with building the clock. What they never could crack, however, was an answer to the economic and environmental crises that inspired them to build it.

The clock is still under construction, though two decades of construction is only a pebble on the road towards 10,000 years. Even in the present, however, the clock is impossibly remote. Once it is built, people will need to burn time, money, and carbon on a plane ticket and a car trip to ever see this thing in person.

For all its grand trappings, the clock lacks any discernible statement, which is by design. “I had never thought of the clock as a question,” Hillis wrote in the 1995 essay proposing the clock. “It was more of an answer, although I wasn’t sure to what.” Since then, Long Now’s founders have given some hints as to what questions of the future they like best. In 2015, Brand, Long Now’s president, signed onto a document called “An Ecomodernist Manifesto,” which serves as a useful distillation of the final argument that Long Now and Jeff Bezos are making together. The Ecomodernists, argue that any reduction in human consumption on Earth is “so theoretical as to be functionally irrelevant,” and that “[c]limate change and other global ecological challenges are not the most important immediate concerns for the majority of the world’s people. Nor should they be.” Instead, they claim, most people should stick to worrying about meeting basic needs, while the technological and political elite handled the existential ones. “Meaningful climate mitigation,” they write, “is fundamentally a technological challenge,” which could be solved with galactic leaps in clean technology, nuclear energy, and efficient urbanization.

Brand makes a similar argument in his 2010 book Whole Earth Discipline: Why Dense Cities, Nuclear Power, Transgenic Crops, Restored Wildlands, and Geoengineering Are Necessary. Surviving climate change requires adopting what he calls an “ecopragmatist” approach which would “discard ideology entirely” in favor of boosting the technologies most able to make human life more sustainable in the shortest time. As to the mammoth work of actually convincing the world to choose this path — politics, in other words — Long Now is explicitly silent. Brand, who at age 82 is still extremely online, has a Twitter bio that reads, “President of The Long Now Foundation — which takes no sides.” Somehow, the same cohort of business and defense heavyweights who currently run the world will spontaneously devise a better one.

Bezos sees things the same way. It is not our current political economy’s insatiable demand for fossil fuels that’s the problem, but rather that we’ve outgrown our supply of energy and should go looking for more. “We go to space to save the Earth,” Bezos tweeted in 2018, alongside a photo of himself standing next to a melting glacier in Patagonia. In this infinite quest for more resources to exploit, the role of politics in halting the climate crises is all but irrelevant, a chaotic sideshow compared with the streamlined world of technological development. When Bezos talks about the clock, he frames its future as an endless, unknowable frontier. “Whole civilizations will rise and fall,” he told Wired in 2011. “New systems of government will be invented. You can’t imagine the world — no one can — that we’re trying to get this clock to pass through.” Mustn’t someone imagine it, though, if the clock is to ever make life better for people on Earth? If the future Bezos imagines is anything like the present, most of us will be priced out of ever jetting beyond the blue marble anyway. (Current tickets on planned Blue Origin suborbital space flights could reportedly run between $200,000 and $300,000.) Between now and Bezos’s future — in present time, not deep time — no one will be called upon to make any sacrifices or work against their immediate wants, especially not Amazon or Bezos. They’ve made a great show of pretending, though.

In 2019, after years of being a bit of a laggard compared to rivals on renewables, Amazon made a belated, gigantic commitment to becoming the world’s most sustainable corporation. That year, after previously rejecting a shareholder resolution with the same goal, Amazon rolled out its Climate Pledge, a promise to run on 100% renewables by 2025, and reach carbon neutrality by 2040, a decade before the Paris Climate Accord. Bezos has committed to donating $10 billion personally through his Bezos Earth Fund and has already awarded $791 million to major environmental organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund, World Wildlife Fund, and the Nature Conservancy. Amazon has pledged another $2 billion through its own fund. Other large companies like Microsoft, Nestle, and Unilever, have followed suit and joined Amazon’s Climate Pledge. In 2020, Amazon bought naming rights to Seattle’s new stadium, Carbon Pledge Arena, which aims to be the first zero-carbon arena in the world, aside, of course, from the carbon used to build it.

In terms of emissions, Amazon is basically the size of a nation state, with a carbon footprint bigger than Denmark’s. Any change within affects most everyone on Earth one way or another. But Amazon’s reforms aren’t exactly radical. The climate pledges aren’t even a double-digit percentage of Bezos’s personal fortune of more than $180 billion, let alone Amazon’s $1.7 trillion value. So far, Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund has invested in manufacturers of low-carbon concrete, high-efficiency electrical systems, and Amazon-integrated electric delivery vans — climate solutions conspicuously helpful to a global retail giant.

The yardsticks Amazon uses to measure progress have their problems, too. The Carbon Pledge’s carbon neutrality formula doesn’t fully account for the third-party sellers and manufacturers that produce a majority of Amazon’s emissions, according to Greenpeace. Per its most recent data release, the company increased its carbon footprint by 15 percent between 2018 and 2019, but used creative bookkeeping to suggest an even bigger expansion in sales meant an overall decrease in “carbon intensity.” The goal is not to shrink Amazon’s overall footprint on Earth, per se. That would mean forgoing money. Instead, non-stop growth pursued in a more “sustainable” way is apparently sufficient.

Amazon and Bezos aren’t keen on making bold political statements either. The only people the Amazon regime is comfortable with targeting directly are its own workers. After a mass employee walkout in September 2019, the company fired multiple employees who had publicly criticized its environmental policies. (Amazon argued they had repeatedly broken company policy.) Amazon analysts created social media burner accounts to monitor environmentalists, and the company hired Pinkerton detectives to surveil its warehouse workers, Motherboard reported. (The company denies any wrongdoing, claiming that creating anonymous profiles is against its policies and that its security and intelligence practices are in line with those of any multinational corporation.) Despite demands from some Amazon workers, the company hasn’t agreed to stop donating to politicians and think tanks that deny climate change. What’s more, Amazon continues to help fossil fuel companies optimize operations, arguing the partnerships will help oil firms decarbonize in the long run. “We need to help them instead of vilify them,” Bezos said in 2019.

In addition to Pinkertons, Amazon has no problem working with the U.S. armed forces, who are by some estimates the single biggest greenhouse gas producers in the world. Amazon supplies ICE and the CIA with cloud computing services. Like fossil fuel companies, Amazon views the U.S. defense establishment as a polluter too influential, and perhaps too profitable, to be ignored. “If big tech companies are going to turn their back on the U.S. Department of Defense, this country is going to be in trouble,” Bezos said at a Wired summit in 2018. “We are going to continue to support the DoD and I think we should,” he added.

Taken together, the interrelated environmental visions of Long Now, Amazon, and Jeff Bezos form a big tent for big people only. Inside, there’s space for billionaires, millionaires, the defense establishment, the tech establishment, Republicans, climate deniers, oil companies, the solar system, and 10,000 years of deep time. Meanwhile, activists, workers, and climate refugees are asked merely to stay out of the way and survive until the global business network and the Global Business Network find a high-tech fix for all of our future ills.

I wasn’t able to see the clock, but I did manage to see one of Jeff Bezos’s other landmark environmental projects: the wind turbines of Tehachapi, California, which borders the Mojave Desert. Here, Amazon has funded a wind farm that gathers enough energy to power up to 14,000 homes each year, but funnels it to Amazon’s cloud-computing business, the company’s main (and sometimes only) profit center. How much impact Tehachapi will make on Amazon remains unclear and uninspiring. Unlike its rivals, Amazon doesn’t publish detailed statistics about how much energy its various businesses consume. But given that the company controls about half of the world’s public cloud infrastructure, it’s safe to say Amazon is going to need a lot of windmills.

Tehachapi was a noble sight. The chunk…chunk…chunk of turbines turning over in the wind sounded like docked boats bumping in the night. Fields of Joshua trees spread across gentle hills, and the turbines looked like the solemn obelisks of some wise and ancient alien race. Guys in utility vests buzzed around in pickup trucks writing important things on clipboards. The place, if you didn’t think too hard, radiated action, abundance, employment. A clean slate. A new way of doing things, where those with the most did the most to make a positive impact on the environment and all who depend on it. But there are no clean slates on Earth, in the scheme of deep time or even right now — “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end,” to borrow from Hutton.

In How to Do Nothing, Jenny Odell writes about what she calls “the impossibility of retreat” — how the utopian communes of the 1960s and ’70s never quite pulled off to their goal of constructing better alternatives to the dying planet and the shredding social fabric. Despite adopting radically different modes of dress or living, many intentional communities shipwrecked in a matter of years or months on the jagged old reefs of politics, amid internal, eternal arguments about class, gender, money-making, and ideals. Building a new world means on some level diagnosing, in explicit terms, what was wrong with the old one, and doing something substantively different. The communes showed “how easily an imagined apolitical ‘blank slate’ leads to a technocratic solution where design has replaced politics, ironically presaging the libertarian dreams of Silicon Valley’s tech moguls,” she writes.

Monuments like Clock of the Long Now, or the Bezos-in-space industrial complex, with all their contradictions, suggest another layer of impossibility: their builders can’t escape politics, and everyone else can’t escape the politics of their builders. Those with the most power are the ones most responsible for creating the environmental and societal chaos we live in today, and those elites will suffer its consequences the least, if at all. Accordingly, the solutions these people propose never viscerally grasp the magnitude of just how much needs to change. Barring a substantial redistribution of power and wealth, in the world of the global California Ideology, the masses will have to sit and wait for our ticket to space station utopia while the Earth burns.

I left Tehachapi not long after I got there. The smoke from nearby wildfires was so thick, even in the middle of the desert, that I couldn’t stay outside for long without coughing. Nowhere is far enough away to escape the long shadow of the climate crisis and the men who created it, and no one person, even with the wealth of many, can solve things entirely on their own terms. It’s comforting, for some, to believe that in a few millennia, we’ll invent some technology that can circumvent the painstaking work of true human coexistence. But unless we attempt that work now, no one will be around to find out if Jeff Bezos’s 10,000-year bets were right.

Josh Marcus is a writer based on planet Earth.