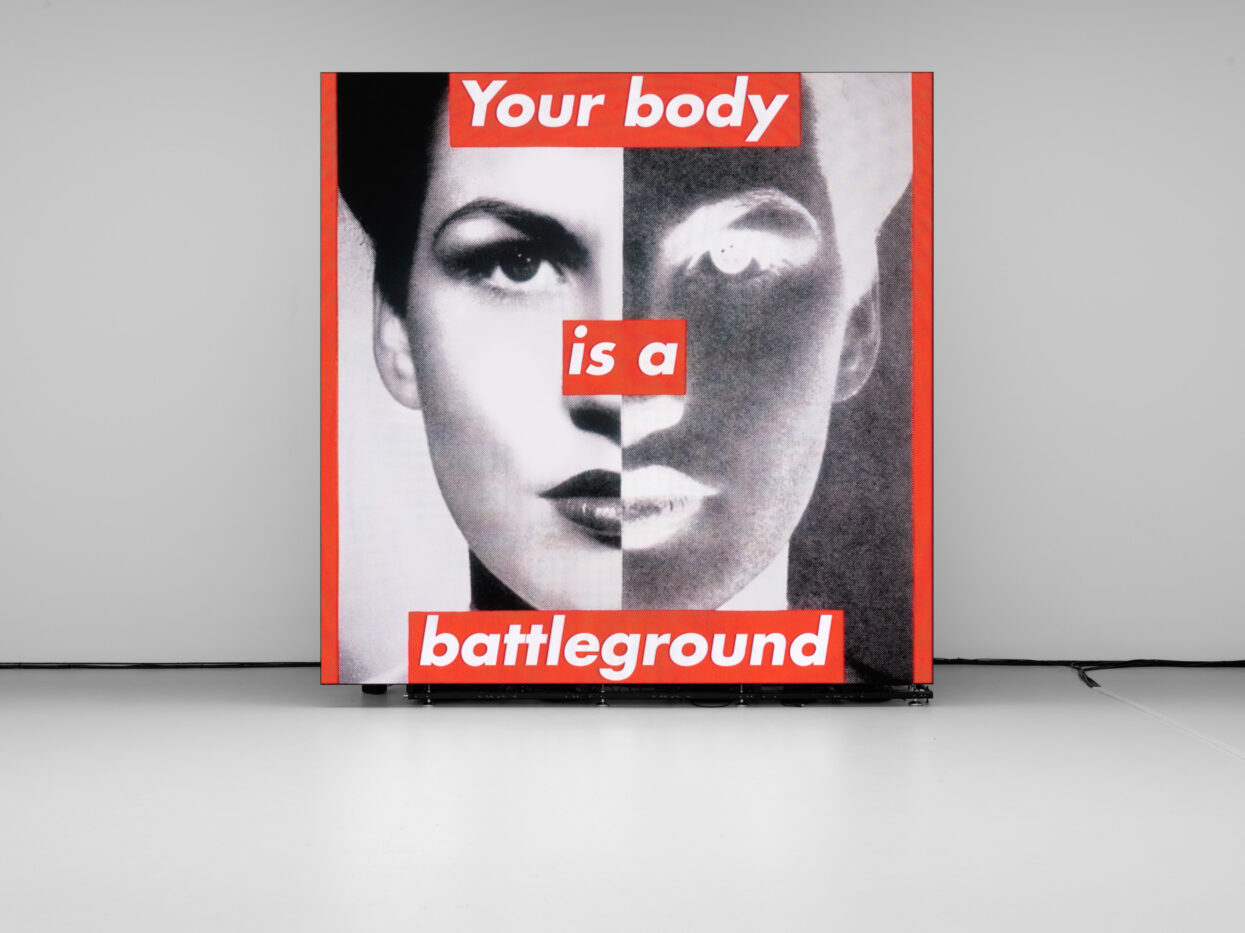

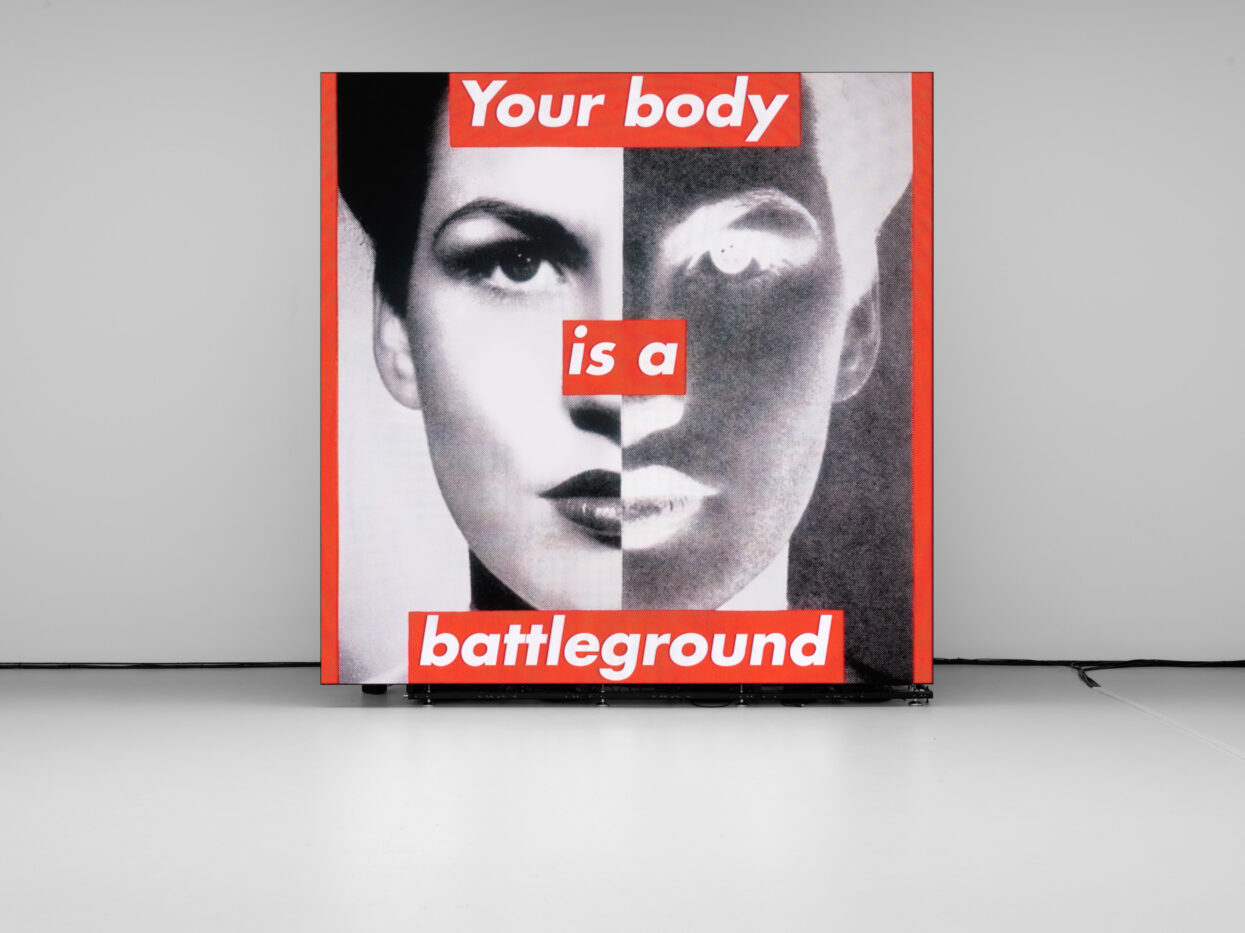

All Images: Installation view, Barbara Kruger, David Zwirner, New York, June 30–August 12, 2022. Courtesy David Zwirner.

All Images: Installation view, Barbara Kruger, David Zwirner, New York, June 30–August 12, 2022. Courtesy David Zwirner.

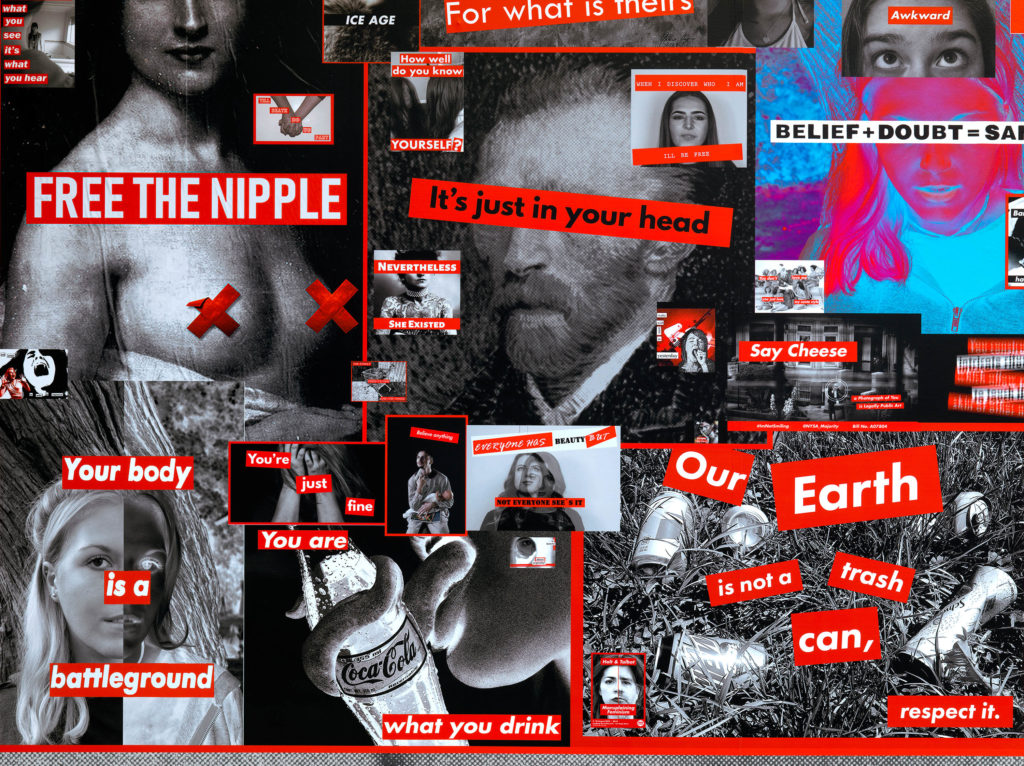

When news broke in June that the Supreme Court had struck down Roe v. Wade, we were not the only ones who thought back to Barbara Kruger’s iconic silkscreen “Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground).” Originally created in 1989, the piece, for better or worse, remains timely — like much of Kruger’s other work. Her immediately recognizable and frequently imitated style has resulted in some of the most indelible images in contemporary art. At 77, she is still working — producing art that is entirely original, as well as revisiting older pieces with a new slant or in a fresh medium. This year, a retrospective spanning four decades, Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., has traveled the U.S., offering an opportunity to reflect on the breadth of her influences and influence. Kruger is omnivorous, drawing from advertisements, the internet, right-wing message boards, memes, and even previous appropriations of her own pieces, from the fashion label Supreme’s mimicry to Krugeresque images pulled from Tumblr. Primarily comprising large-scale installations, the show brings together large-scale collages, sound pieces, annotated texts, and video works that juxtapose kittens with right-wing political rhetoric.

Over Zoom, we talked with Kruger about her career, media diet, and political views; the internet; the ever-churning flow of images and words; and — what else — reality television.

One of your most famous pieces — “Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground)” — was initially made for the 1989 women’s march on Washington, which was a protest for legal abortion. How have you thought about the newer iteration of the women’s march, and the overturning of Roe v. Wade?

I just hope that all those folks marching for reproductive rights and privacy for all bodies had the power of the Supreme Court in mind when they voted in the past few presidential and midterm elections. Their choices, considering the closeness of those elections, brought us the composition of the current court. What’s happened in terms of Roe was so predictable and could have been avoided. It is more urgent than ever that people vote strategically and realize how their votes, because of the courts, will determine the feel of your (our) days and nights.

I don’t vote “my conscience” because the world is bigger than my or anyone else’s narcissistic conscience. For years, many third-party candidates assured us that if Roe was overturned, it wouldn’t be a problem because it would simply become a state issue. This was always uttered by a man without a uterus. I cannot be an apologist for the incrementalism of the Democratic Party, but I have to vote strategically. I will not forget the era of Bush v. Gore, when many votes cast around the University of Florida, along with the power of Sandra Day O’Connor, brought us the beginning of the current rightward cast of the Supreme Court, which in fact began even earlier with the egregious Clarence Thomas.

The “old left,” even when it was made up of young college students, was never what you could call “intersectional.” It continued to marginalize the issues of gender and race, refusing to see the necessity of engaging these concerns simultaneously and with urgency.

Trump is not responsible for all of this. I mean, the right has been watering these noxious weeds of grievance and supremacy for almost three centuries. But the genie is totally out of the bottle now. And no one should be surprised.

In some of your most recent work, you engage explicitly with Trump’s presidency —

I would dispute that. Yes, there were two moments in “Untitled (No Comment)” where there were split-second images of Trump and there were pictures of Michael Cohen. I’ve done covers for The New York Times and New York [including an October 2016 image of Trump’s face with the word LOSER across his nose in Kruger’s trademark Futura Bold Oblique] that were very specific moments — they were incident-related — but most of my work has really not been that. I try to take a broader view of how power is threaded through culture and how we are to one another, how we adore or abhor one another, how we caress or kiss or slap one another. Those have been concerns of mine. But I really don’t think it’s so much about Trump. It’s just that Trump is an excellent salesman and lots of people are buying what he’s selling.

I don’t make political art. I don’t make feminist art. I’m a woman who’s a feminist. I don’t make women’s art. I think those categories marginalize anyone’s work. I’m engaged with ideas of power and picturing, of pleasure and punishment, of lives and their beginnings and ends, and how, amid moments of pleasure and tenderness, there are explosions of destruction, subjugation, and the insanity of war.

Something that struck us, as we walked through your show, was that your work seemed to be critiquing and playing with the tropes of the internet much more so than art by many of our internet-native contemporaries. What has your experience with the internet been, and what about it do you mean to critique?

I wouldn’t even use the term “critique.” I mean, I don’t even know what that means on a certain level. In regards to “Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am),” I was considering the immersive power of market cultures, whether they’re rural or intensely urban, whether they’re brick-and-mortar or digital. What I’m doing is looking at the way our lives have become to some degree a sort of crash site for narcissism and voyeurism. Can we continue living lives without being in front of the lens, or behind the lens? If you’re in a museum and you take a photograph of an object, that’s not enough — you have to be in the object, in that image. It’s very telling, the I-was-here-ism of it. I was here. This happened. I’m here. See me. These are my “likes.” Maybe this is what “proof of life” means now.

What’s driving that tendency?

I do feel that the availability of images and their dispersal, whether they’re pictures of things we look at or how we look at ourselves — the fact that those images are available and that what we have to say about them is available instantly — changes the moments of our lives. What does “Be Here Now” mean? Does it mean “be here in the moment” or “record that moment”? These are differences that have cropped up because of changes in reception, methodology, and technology.

How much are you talking about people of other generations, and how much are you including yourself?

I’d rather go to hell than have my picture taken. But that comes from my years of rifling through photographs at Condé Nast. I was a picture editor there, looking at the models, the clothes, the bodies, the market economy of merchandise, and how bodies are part of that merchandise. But I also think that, on some level, there should be a recognition of power, of what it means to point the camera at another person. It changes when you’re pointing it at yourself. Generations of street photographers and photojournalists have looked for the most horrific events, the most divine oddities, the most “other” others. I think much of image “capturing” carries with it the possibility, if not inevitability, of exploitation. In many ways, conventional photojournalism and so-called “street photography” have remained woefully unexamined forms of picturing. But when people choose to do it to themselves, that’s another form. It changes.

The words “you,” “I,” and “me” come up again and again in your work. How do you think about universality and individuality? Who is the “me” and who is the “you”?

I don’t think about “universality.” I would be wary of its reductivism and dissolving of difference. And as far as the “you,” the “we,” and the “I” are concerned, I’m just considering how subject positions work, how address works. Direct address has always been a motor of a lot of my work. But I don’t think that there is a specific or stationary “you,” “they,” and “we.” I think it’s a broader field of fluidity. You can either decline the address or accept it or feel somewhere in between.

Over the years, as your work has become increasingly famous, many people have appropriated your images, and your newest work incorporates some of those appropriations. Does that feel to you like a collaborative or a critical exercise?

It feels like neither of those things. I would say that it never ceases to amaze and amuse me — and please me, to a degree — that my work has entered the culture the way it has. I never thought people would know my name or my work, so this is just another example of the arbitrariness, the role of historical conditions and social relations that gather to determine who is seen and who is not, who is heard and who is not. And the viral spread of images, words, and proper names has accelerated and influenced everything.

I think the advent of film, radio, television, and the internet have presented different opportunities for direct address. And of course, online lives are so about the promises and punishments of direct address, not only through texts but eye-to-eye, or ear-to-ear ASMRing.

I’ve always thought it was important to keep in mind just how absolutely marginalized the visual arts are in this country. Who thinks about it? Almost no one knows the names of many artists, and I don’t assume anybody knows who I am except within certain narrow subcultures. But now, as I approach my centennial, all of a sudden there’s this institutional support. More people have seen my work and it travels digitally and virally in ways that it never had. But I think it’s important to realize that so-called “art worlds” can be very narrow and confined sites. But I really view art in a much more expansive sense: an aerosol of commentary, an enormous visual, filmic, sonic, and textual creation of what it means to be alive at a specific time. An ability to visualize, textualize, and musicalize the experience of the world.

Does that inform your approach as a teacher of visual art?

Well, it has. I actually stopped teaching this year. But, you know, I’ve always taught at a public university, not an art school. And since I have no undergraduate degree and no graduate degrees, it was important to me that if I did teach, I was at a public university with many first-generation students, first-generation families, first-generation-to-speak-English students. It meant something that these young people were at public universities and junior colleges that offered a very broad perspective of what they could make of their lives, rather than a private art school where even the youngest students might already be developing art career strategies. That’s not wrong. But I did not think it was the context in which I could be of too much assistance.

Do you feel more at home in that kind of environment than the gallery-verified art world circuit?

I had always found the art subculture very intimidating. Every time I’d walk into a gallery, I used to feel I had to have a lint brush with me, just the notion of perfection and all that. Young artists figure out ways to support themselves — some of them choose to be artists’ assistants or work in galleries. I could never pull that off. For me, it was very much a class issue. I just worked nine-to-five jobs for many years.

Has anything changed? Are there developments in the art world that give you hope for its future?

Well, of course it’s changed. I mean, thank goodness it’s changed, but it’s still an ongoing struggle. I recall when it started changing for (white) women in the early ’80s. But now we’re seeing huge shifts in power and representation. So many more people can easily call themselves artists now. It took me a long time to see myself as an artist. As I’ve said before, the “art world” just looked like twelve white guys in Lower Manhattan. But it was always much more than that. So many artists were marginalized and made invisible on so many levels. The exclusionary powers of race, class, and gender determined who was seen and who was not. We’re seeing a historical reset, which is absolutely urgent and necessary — even given the fact that some of it might be fueled by an intense speculative market and multiple apology tours.

Your new show revisits some of your older pieces. What does it mean to you to return to earlier works, and to think of art more broadly as an ongoing practice that’s oriented towards the present?

It’s only in the past four years, when I was constructing this exhibition, which was put off for a year because of Covid, that I went back to those works. What becomes “iconic” and what doesn’t, what enters the canon, accrues value, or is deemed worthless? As I edge into what may be a very temporal canonicity (say, for the next twenty minutes), I have to consider the fickleness of taste and value. Of what is forgotten and disinterred by art historians twenty years later. Everything is so fueled by market fickleness. It is a very complicated mix of what emerges visually and who becomes a proper name and who doesn’t. And I’ve always been so aware of that because I’ve been on both sides of it, and in the middle. Many years ago I did a show called Picturing “Greatness,” which was a look at how the construction of greatness happens — the arbitrariness, the investment, buzz, and rumor of it all. For folks who actually believe in greatness, well, more power to them. But for me, it’s such a construction of inflationary markets and claims. I’ve said that no work of art, no painting or sculpture or movie or piece of music or building is ever as major and important and brilliant — or as damaged and minor — as it’s written to be. Everything is an overstatement. It’s either a selling point or comes from a need to believe in the idea of “the masterpiece,” or the extraordinariness of a particular creator. All that stuff is just part of the deal, but I tend to look at it in a kind of vigilant way.

Is there anything else that you’d like to talk about?

Well, something I have been thinking about is the fluctuating interest in narrativity and the stretching and compression of attention spans. Certainly, the movie studios have felt the near collapse of brick-and-mortar viewing and chosen to invest mainly in big “event” movies and franchises. In many ways this seemed to diminish the power of storying and the narrative strategies of conventional smaller films. Attention spans seemed more attuned to episodic viewing. And my work itself, my visual moving image work, is very episodic, rather than narrative in a linear sense. But digital streaming has brought both a new interest in narrative and a huge affection for, if not addiction to, episodic viewing. If you’re not watching movies, you’re watching more serialized, T.V.-style stuff. Pre-Covid, narrative took too long — is this over yet? We’re so used to accelerated online reading, whether it’s memes or fast stuff, you know. And I think that the segmentation of narrative through streaming has opened things up to more narrative, but in the bits and pieces and episodes. We see things streaming that would never have been greenlit by the old studio system.

I had never watched BoJack Horseman before Covid, and to me, that’s a work of art. I mean, the people who were writing that shit must have been on mushrooms, because it was such a really strong take on tragedy. On living or dying. It wasn’t just funny. I mean, I cried in parts of it. Watching all of Jordan Peele; Ozark was so amazing; Steve McQueen’s Small Axe, all five of those films, was just absolutely incredible; Euphoria, even though it could be so overdetermined, was so visually powerful. But all of these works still felt episodic and segmented. It wasn’t like sitting in a movie for three hours, you know? From the beginning of Covid, when I didn’t leave L.A. for nineteen months, I streamed so much terrific stuff and also reality T.V. And the “reality” T.V. was an escapist lifeboat. Can you imagine? Reality T.V. as a delivery device for sanity. Such is the world.

What reality T.V. do you watch?

Well, much less of it now, but Real Housewives of all locales, Black Ink Crew of all locales, Vanderpump Rules, 90 Day Fiancé, pretty much all of HGTV. Absolute real estate porn.

Your work has always drawn from the lowbrow, including, in this most recent show, online memes and cat videos —

I have to believe that what has always been important in my work is a certain grasp of the goof — a use of laughter that can be both liberating and brutal. Especially in this time of both massive fame and punishing shaming. But nothing works like kitties and puppies. Unless you’re an absolute psycho, puppies and kittens are the mellow zone, you know, the intense cuteness halo. I don’t think that many people are immune to those picturings, and it opens up a different kind of emotional space, which is warmer and often funny.

What do you think it does to put those next to the images of Trump, and next to text you’ve written?

It feels like life to me. I think that’s the best way I could say it. It feels like life.

THIS INTERVIEW WAS CONDUCTED BY REBECCA PANOVKA AND KIARA BARROW. IT WAS CONDENSED AND EDITED FOR CLARITY.