Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

In 2001, the Pakistani government was distributing polio drops in Mohmand Agency, a semiautonomous tribal area bordering Afghanistan, when it learned that the Taliban had been conducting a polio drive in the same villages. Children, it seemed, were being vaccinated twice. According to Fida Muhammad Wazir, a doctor and civil servant who oversaw the distribution, the Pakistanis tried to chase away the Taliban, but local Afghan leaders claimed the villages belonged to them.

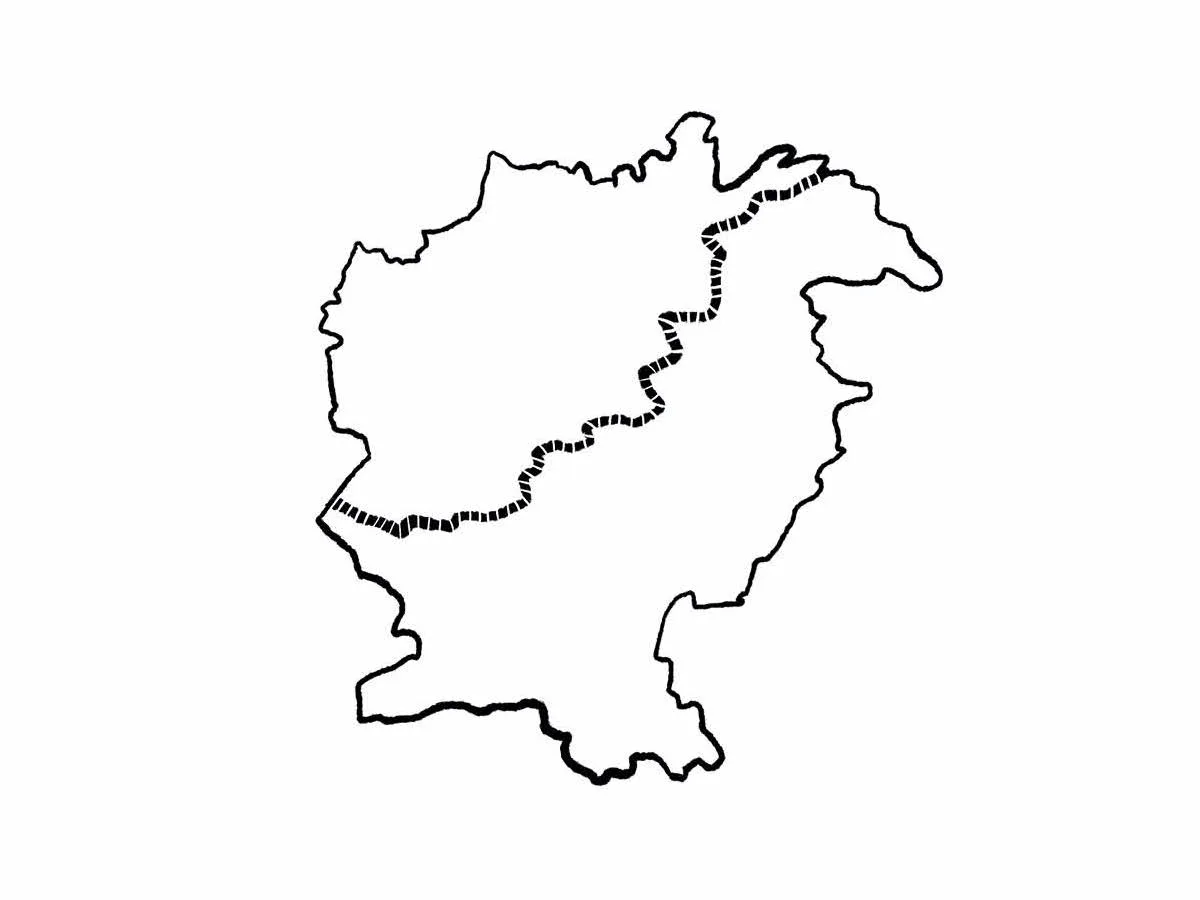

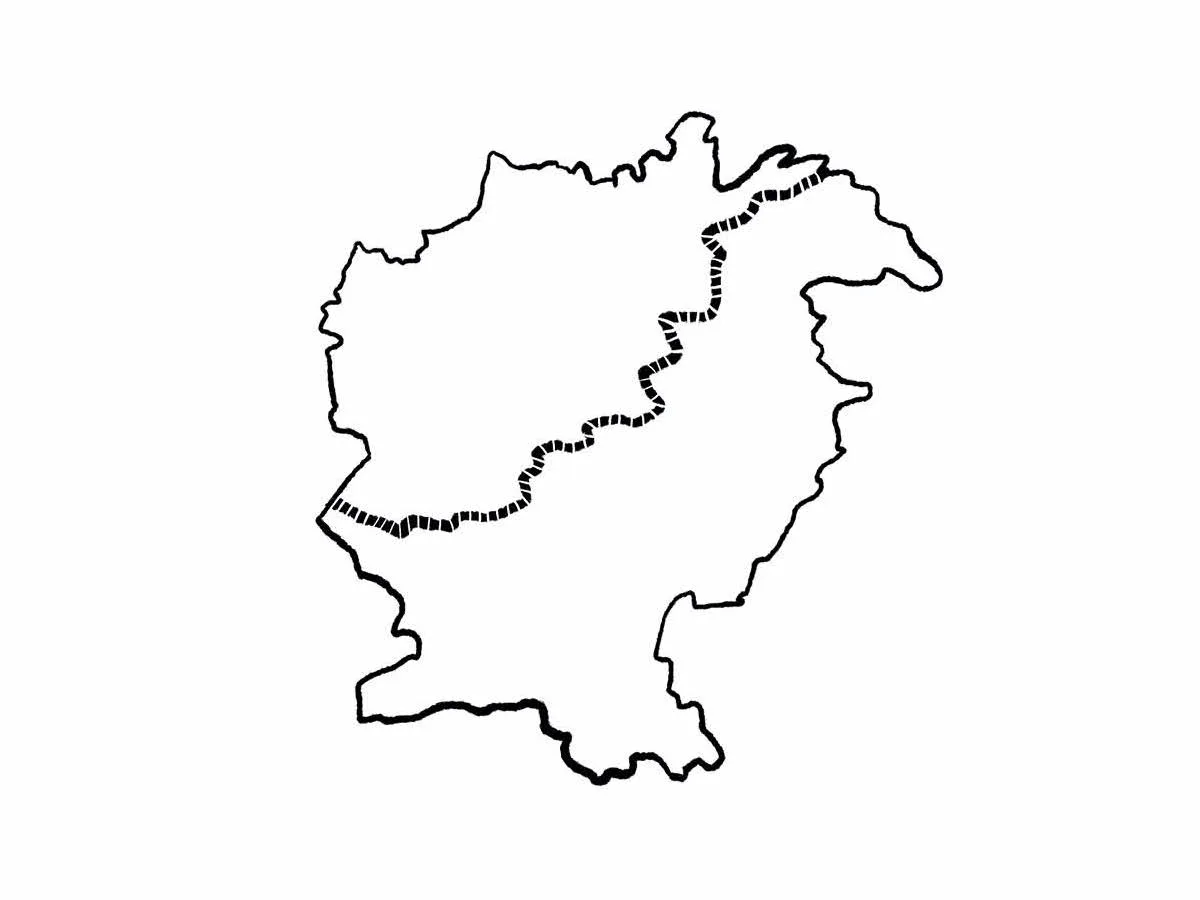

The border between the two countries essentially follows the Durand Line, named for the British diplomat who negotiated the division of the Emirate of Afghanistan and the British Indian Empire in 1893. Henry Mortimer Durand hoped Afghanistan would serve to separate and protect colonial India from Russian influence in the region. Today, the Pakistani government considers the Durand Line “conclusively settled,” per the country’s special envoy to Afghanistan, but no Afghan government has ever recognized the border. As recently as February, the Afghan deputy minister of foreign affairs called it “imaginary.” Though tall Pakistani fences now mark the border in Mohmand Agency, the claim is not entirely unreasonable: the Durand Line cuts across families, tribes, and entire villages.

Afghanistan-Pakistan relations made headlines last fall, when the Pakistani government announced its plan to deport 1.7 million undocumented Afghans, more than six hundred thousand of whom left Afghanistan after the U.S. withdrew and the Taliban reclaimed power in 2021. Many thousands more had only ever known life in Pakistan, born there after their parents fled the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. As of April, around 575,000 Afghans had been expelled in a rushed and chaotic process that forced many to sell off their homes and businesses at steep losses.

With Pakistani national elections approaching, the policy made for good domestic optics. Suicide attacks and targeted killings persist around the border, and in a country contending with its worst economic crisis in decades, anti-Afghan sentiment is high. But Pakistan has faced criticism internationally, including from the U.K.’s Amnesty International, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Meanwhile, analysts in both Pakistan and Afghanistan have speculated that the Pakistani government is trying to punish the Taliban. The Pakistani military helped to train and fund the group — with full-bellied U.S. support — in the 1990s, but the Taliban has since made clear that it won’t reliably act in Islamabad’s interests, harboring jihadis that regularly attack Pakistan’s police and military. The Taliban’s leaders, Pakistani generals sniff, must be reminded who their daddy is.

Meanwhile, the senile grandfathers doze off. The U.S., Russia, and the U.K. are responsible for much of the region’s instability of the past few decades, but have borne a much lighter burden in refugee distribution than have countries like Iran and Pakistan. Even after the recent deportations, roughly four million Afghan refugees and their descendents live in Pakistan. The U.S., by comparison, housed 195,000 Afghan immigrants as of 2022 — 76,000 of whom were granted temporary residency after the Taliban’s 2021 resurgence. About 150,000 Afghan immigrants live in Russia, and fewer than a hundred thousand are in the U.K., Durand’s homeland.

Who must face the consequences of imperial hubris, and who is spared? The U.S., Russia, and the U.K. have successfully evaded responsibility for untold numbers of people displaced by the turmoil left in their wake. One hopes this spell of indemnity will expire soon.

Dur e Aziz Amna’s debut novel, American Fever (2023), won the Asian/Pacific American Award for Adult Fiction and the South Asia Book Award. She is a graduate of Yale College and the University of Michigan’s MFA program