Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

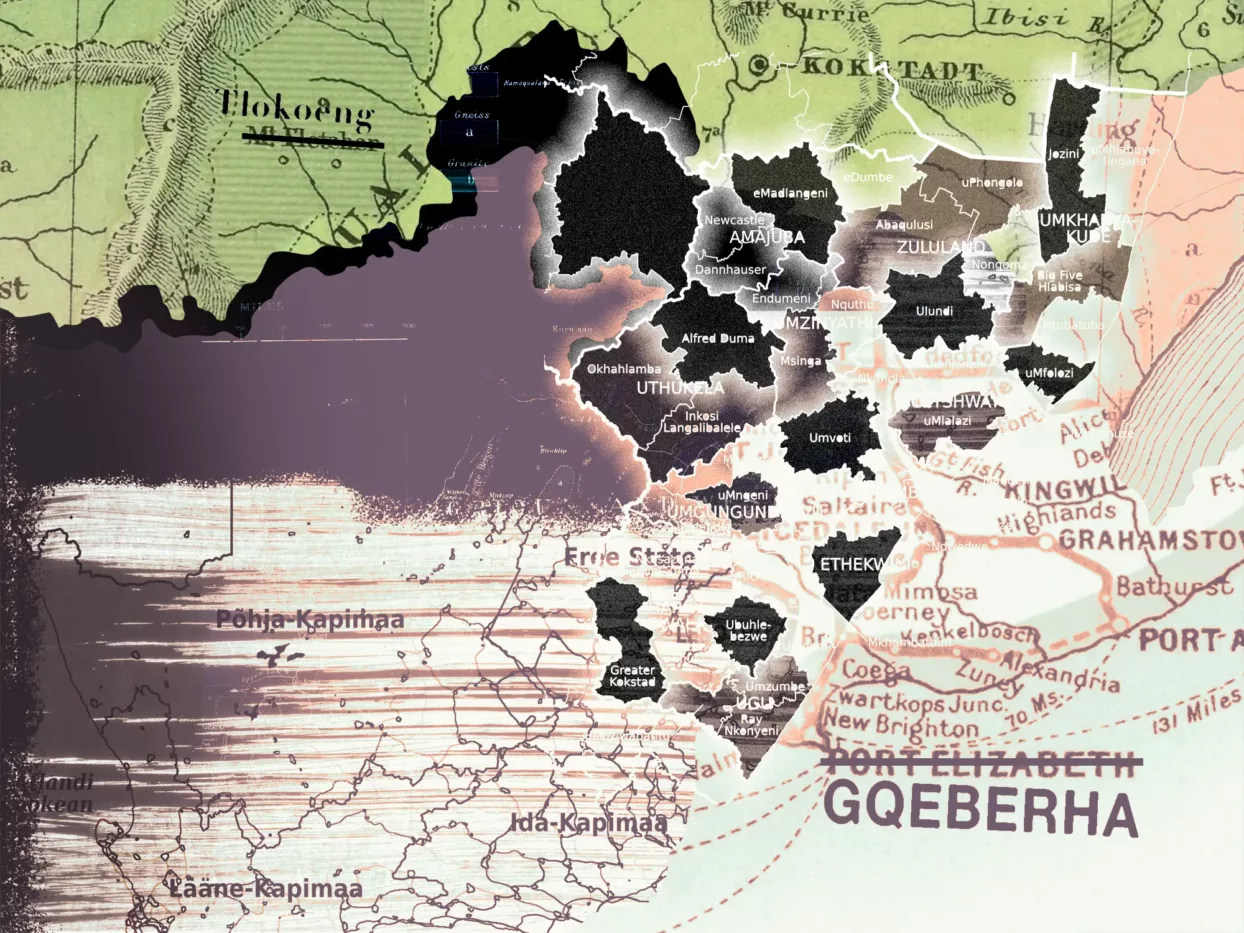

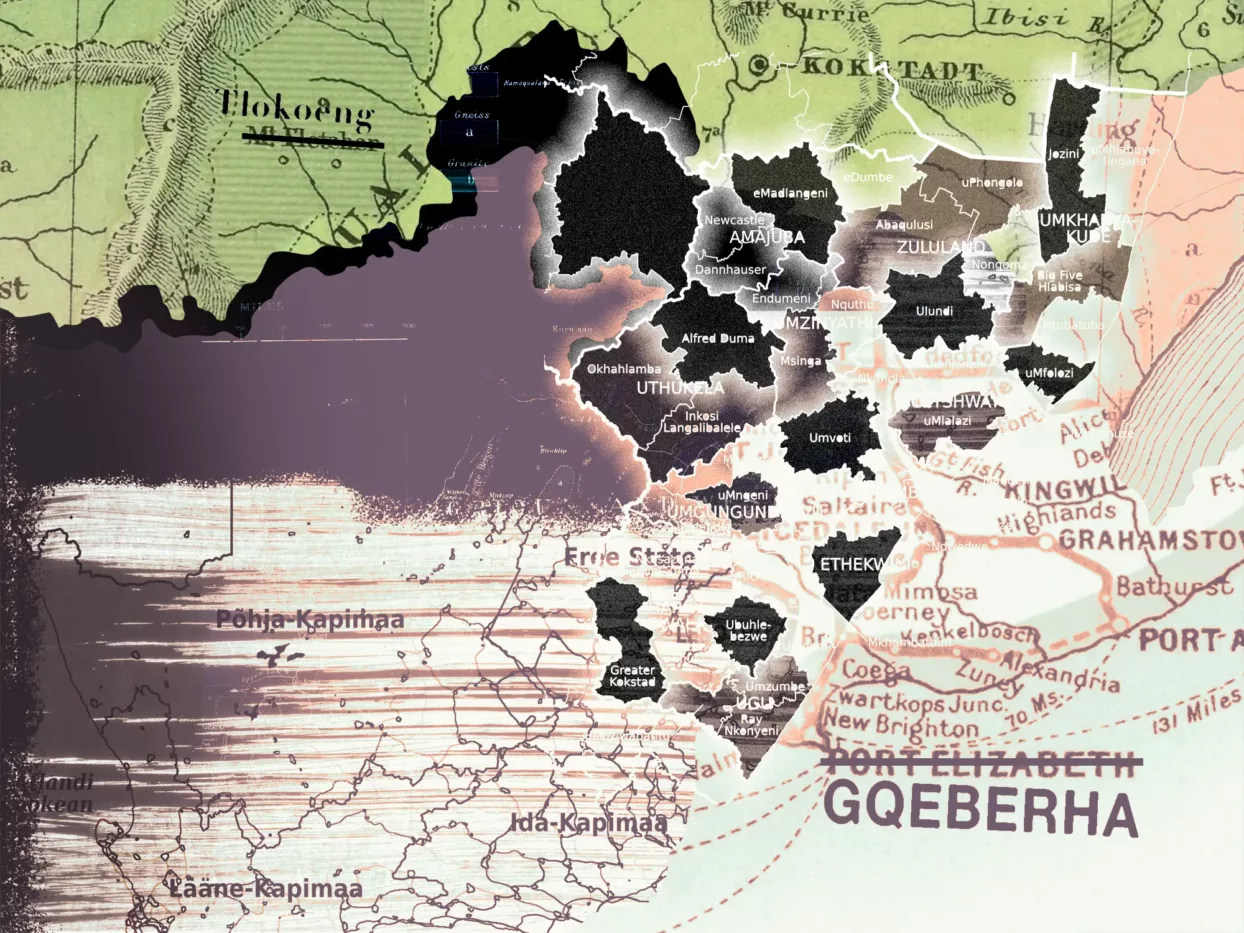

When my grandfather started to die, the first thing he lost was language. Like most people in South Africa, he had been multilingual, fluent in English and isiZulu, competent in Afrikaans and isiXhosa. This ease of passage remained a continual point of pride for him, as the spoken fabric of the country was rewoven after the end of apartheid. When Nelson Mandela, the son of a Xhosa chief, ascended to the presidency in 1994, the country warily embarked on a linguistic transformation. One of the first places to change its name was a town previously called Verwoerdburg, after Hendrik Verwoerd, a former prime minister and the architect of apartheid. In 1995, Verwoerdburg became Centurion, and the renaming of other streets, towns, and cities followed. The nation adopted a new national anthem, which included isiXhosa, isiZulu, English, and Afrikaans. Provinces were redrawn, the segregated Bantustans dissolved. Natal, where my family comes from, became KwaZulu-Natal; the Transvaal was divided into North West, Gauteng, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga. The country’s new composition served as a reminder of how absurd colonial geography is — and of the incalculable cultural damage that colonization had wrought.

Today, South Africa remains a lesson in linguistic chaos: there are twelve official languages, a count that doesn’t include dozens of minority dialects, and the tongues vary from province to province, town to town. Because Afrikaans was the vernacular of the Nationalist Party, and therefore of apartheid, it was demonized in a way that English wasn’t. There’s a prevailing assumption of English’s relative neutrality, even though more people speak other languages — isiZulu, isiXhosa, Afrikaans — at home. (In KwaZulu-Natal, over 77 percent of the population speaks isiZulu as a first language, while English stumbles in at 13 percent.) Still, the predominant language of government is English; road signs are in English; the national public radio station SAfm broadcasts mainly in English; few universities offer degrees in anything other than English, and until recently, final high school exams could only be taken in English and Afrikaans. As a result, living a successful life solely in one’s mother tongue is a privilege denied to most South Africans. If Afrikaans is an overtly colonizing language, English is its quiet, violent cousin.

The author J.M. Coetzee put it another way. English is not only a “deeply entrenched foreign language” in South Africa, but an invasive species: it belongs, he wrote in 1983, to the “downs and woods, badgers and stoats, cuckoos and robins” of Britain, and bears no relation to the velds, mountains, and deserts of South Africa. As the winner of two Bookers and a Nobel, Coetzee, at age 83, is arguably the most successful South African literary export. Tall, discerning, silent, liable to sit through a dinner party without saying a single word, he is a master of the English language, but possibly the most reluctant master imaginable. His vast body of work wrestles with uneasy linguistic dynamics — particularly those of his home country — and continually, cleverly subverts them. Over the last two decades, though, he has drifted away from the context that made him famous, resisting the national and stylistic categories that critics tried to impose. He left South Africa in 2002, and in 2006 became an Australian citizen. He hasn’t written a novel set in South Africa since 2009. With his latest, The Pole, published this fall, Coetzee has attempted to renounce English altogether, in an uneven book that epitomizes — for better or worse — an artist’s lifelong rebellion against his own medium.

Coetzee managed to establish a singular position for himself in large part because he sought to close the distance, through work and education, between his relatively provincial upbringing and the international literary milieu of the Global North. He was born, in 1940, to a culturally Afrikaans but Anglophilic family. He has said that as a child, in the company of his father’s relatives, he never heard “an Afrikaans sentence without an English word in it, and vice versa.” In school, he learned English from teachers for whom it was a second language. “I have always approached English as a foreigner would,” Coetzee has remarked, “with a foreigner’s sense of the distance between himself and it.” Coetzee is partly descended from Dutch settlers who arrived as early as the seventeenth century, and he grew up in a racist apartheid state — a colonial outpost of a fading British empire. There was, and still is, a clash between South Africa’s two white populations, and between their attendant stereotypes: the unsophisticated Boer, who farms and drinks and brushes up against poverty in the country’s interior, and the coastal, snobbish, big city Anglo.

Yet the South Africa of Coetzee’s youth, isolated geographically and intellectually from the major cultural hubs in the U.K. and Europe, saw comparatively limited literary offerings in English. In a 1991 essay, Coetzee characterized the national body of English-language literature as one that “followed London’s lead” and was “shaped to an unusual extent by women writers” like Olive Schreiner, Pauline Smith, Sarah Gertrude Millin, and Nadine Gordimer. Of those, only the Booker- and Nobel-winning Gordimer can really be classed as global — mention of the other names outside of South Africa will win you unrecognizing smiles. Both Gordimer and Schreiner failed to earn university degrees, and they were largely self-taught, which, Coetzee noted, “says something about the fierceness with which isolated adolescents on the margins of empire hungered for a life they felt cut off from, the life of the mind.” It’s difficult not to draw the same conclusion about Coetzee himself.

In a speech, Coetzee once confessed the desire to “disown our real parents and claim for ourself a much finer-sounding lineage.” The fine lineage he sought was an esteemed group of exiles who slipped between languages and countries. He has referred, in various places, to Rainer Maria Rilke, Jorge Luis Borges, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Zbigniew Herbert as literary influences — writers also trying to transcend their national and historical contexts. Rilke “did not wish to be an Austrian or a German” and attempted to remake himself several times over, Coetzee wrote in a 1999 essay. Borges, he argued in a different piece around the same time, drew from dual English and Jewish backgrounds to present himself “as an outsider to Western culture, with an outsider’s freedom to criticize and innovate.” He has suggested a kind of kinship with Herbert, a Polish author who was also writing against his nation, and who described himself as “a citizen of the earth” and “an inheritor of almost the whole of infinity.”

It is easy to trace the influence of these and other canonical writers in Coetzee’s work. Life & Times of Michael K (1983) was, Coetzee has admitted, a sly attempt at reclaiming the letter “K” from Kafka, whose Josef K. navigates a pointless bureaucracy in The Trial in much the same way Michael K. stumbles through an unnamed civil war. Foe (1986) is a postcolonial subversion of Robinson Crusoe. The Master of Petersburg (1994) features Dostoyevsky as its protagonist. The anti-hero in Disgrace (1999) is a Byronic and Romantic scholar, and the eponymous narrator in Elizabeth Costello (2003) gives an awkward talk on Kafka and Gulliver’s Travels. Nearly every single one of Coetzee’s novels is explicitly in dialogue with another author or theorist. Rarely do these conversations include another South African writer.

In his 1991 lecture “What is a Classic,” a response to T.S. Eliot’s lecture of the same name, Coetzee offered two readings of his experience of listening to Bach at fifteen: that he was touched by the music itself, and that he was moved by the possibility of social ascension. In this second reading, the teenage Coetzee suddenly understood the power of art to transport a listener beyond their context — and, in turn, the power of an artist to transcend their own identity. By hearing and playing classical music, Coetzee observed, he was “symbolically electing high European culture, and command of the codes of that culture, as a route that would take me out of my class position in white South African society.” The consumption of art was not just an aesthetic endeavor; it was an aspirational one. In 1961, after studying mathematics and English at the University of Cape Town, Coetzee left for London, where he found a job in computer programming and immersed himself in cultural offerings. In 1965, he began a PhD in English at the University of Texas, where he wrote a thesis on Samuel Beckett. He stayed in the U.S. until 1971, teaching in Buffalo and working on his first novel.

“South African literature is a literature in bondage,” Coetzee said when he accepted the Jerusalem Prize in 1987. “It is exactly the kind of literature you would expect people to write from prison.” From the very beginning, Coetzee has engaged deeply with the history of South Africa, and with the ways in which language can facilitate colonial violence, often implicating himself in the process. This pattern first reveals itself in Coetzee’s debut novel, Dusklands (1974), which is broken into two parts. The first is narrated by Eugene Dawn, a researcher who, under the supervision of an adviser named Coetzee, becomes erotically obsessed with atrocities committed by American soldiers during the Vietnam War, and eventually goes mad. The other is the diary of Jacobus Coetzee, a Boer in the eighteenth century, and a relation of the fictional Coetzee. Jacobus is racist, bigoted, and almost megalomaniacal — an evisceration of Afrikaner mythology. Both he and Dawn are self-deceiving colonizers, visiting or observing violence upon the margins and becoming hopelessly twisted in the process. Pulsing through both narratives is a disdain for the languages that make these atrocities possible. “We have justified the elimination of enemy villages by calling them armed strongholds,” Dawn points out. In the afterword of Jacobus’s diary, he is imagined riding “like a god through a world only partly named.” But of course it was already named, already known. The “frontiersman taxonomy” that Jacobus constructs is an illusion, just like the U.S. government’s military rhetoric. Here Coetzee is already alienating us from the language that allows us to lie to ourselves.

“I was born into a language of hierarchy, of distance and perspective,” laments Magda, the Afrikaner protagonist of In the Heart of the Country (1977). “Words alienate,” she thinks. She yearns for “a life unmediated by words,” a freedom from Afrikaans and from speech altogether, where she fantasizes that she will be able to participate in South African society not as an oppressor, but as a citizen — a naive wish ultimately unfulfilled. It’s a theme that returns in Coetzee’s autofiction trilogy: in Boyhood (1997), he rejoices in the “happy, slapdash mixture of English and Afrikaans” of his childhood, only to return to South Africa as an adult in Summertime (2009) and discover that his Afrikaans is so bad he’s reduced to the status of foreigner among people who should be his peers. Throughout the book, communication is blocked and thwarted and then only halfway facilitated by translators. These “language problems” push the now-adult Coetzee into a place where he, like Magda, envisions the afterlife as a pre-Babel “Eden” in which no translation — or, alternatively, language — is needed at all.

The fantasy of muteness is one Coetzee returns to again and again. In Life & Times of Michael K, the refusal to speak is explicitly cast as radical. Though the mixed-race protagonist can talk, he prefers not to, especially to people who want to know about his background. “They want me to open my heart and tell them the story of a life lived in cages,” he thinks bitterly, after being urged by soldiers and doctors to tell his story. Well, he won’t: not on terms that aren’t his. Only through isolation in nature — a recurring situation that he calls “the great silence” — does he seem to find any peace. In Foe, Friday, an African man dehumanized by Daniel Defoe in Robinson Crusoe, is actually mute. “Nothing you can say,” Coetzee writes, as his white characters try to make Friday talk, “will persuade him to yield.” The Swedish writer Per Wästberg, in the opening address for Coetzee’s 2003 Nobel win, pointed out the subversive nature of this choice. “Who does the writing, who seizes power by taking pen in hand? Can black experience be depicted by a white person?” he asked. To give speech to Friday, Wästberg said, “would be to colonize him and deny him what remains of his integrity.” Coetzee senses that writing in Friday’s voice would be an act of appropriation. He would become no better than the officers, who wait for Michael to speak only so that they can misinterpret him.

A decade later, post-apartheid, Coetzee was still trying to disrupt the function of language in his home country, even as he prepared to leave for Australia. In Disgrace, David Lurie becomes increasingly “convinced that English is an unfit medium for the truth of South Africa.” Lurie, who initially intends to complete an opera about Byron, has his highbrow ideals shattered when his daughter, Lucy, is assaulted by three black strangers. Lucy’s subsequent decision to stay on the farm and marry a black worker is literally inexplicable; she cannot explain it to her father. And if English is an unfit medium for the truth, what should we make of Disgrace itself, which must by extension contain untruths? Coetzee seemed to feel that the only workable option for a South African novelist working in English — someone who will always be committing a kind of colonization simply by writing — is to destabilize the languages of the white minority and undermine his own authority.

Accordingly, Coetzee tends to maintain a gulf between reader and text that might, on first glance, be mistaken as coldness or cruelty. His prose is not inviting, or obviously funny; there are stutters in comprehension, labyrinthine structures, authorial self-insertions, and entire sentences or paragraphs in Afrikaans or, later, in Spanish. Somebody has their tongue cut out; somebody else speaks an unintelligible language. While his characters attempt desperately to communicate with each other, stretched to their moral limits, the reader races to catch up. This is neither cold nor cruel; it’s just a recognition that trying to project the fullness of emotion and experience via language will necessarily fail, and it’s only by inhabiting that failure that writing becomes most affecting.

Over the course of a long and varied career, Coetzee’s embrace of surreality and interrogation of language’s ability to sustain nationalist propaganda has made him a key figure in the development of postcolonial writing, though he has not been universally adored. For those who wanted to see in Coetzee a representative of South Africa and a spokesperson for its literature, his silences and ambiguities have proven maddening. In the absence of overt criticism of apartheid, it is easy to read a kind of tolerance and small-mindedness. Gordimer accused Coetzee of “a revulsion against all political and revolutionary solutions,” and the critic Michael Vaughan has skewered him for giving “privileged attention to the predicament of a liberal petty bourgeois intelligentsia.” He has been alternately criticized for furthering the “demon of white racism” (according to the African National Congress, circa 2000) and praised as a brilliant “son of this soil” (also the African National Congress, circa 2003) — a fierce freedom writer, or a bitter white man with a reputation for mean bleakness and harsh sentences. Always, he is playing with the reader, experimenting with documentation, translation, and narrative expectations.

Twenty years after Coetzee won the Nobel, his explorations of the constraints of art, language, and his own identity have reached a zenith in his latest novel. The Pole weaves together threads from Dante, Chopin, and, slyly, from Coetzee’s own Polish heritage, to present a brief, often acerbic portrait of an old man’s last attempt at love. Like his last two novels, The Pole was released in Spanish before English: published in 2022 as El polaco, by an Argentine press, El Hilo de Ariadna, it came out in English a full year later. Though it is Coetzee’s first novel set in Spain, it’s not his first with Spanish-speaking characters. His Jesus trilogy takes place in an unidentified land where Spanish is the common tongue, but the backdrop remains stubbornly ahistorical and almost featureless, free of any specific colonial past. Not so with The Pole, which is set in Barcelona, along with Mallorca, and very briefly Poland. Of Spanish cities like Barcelona, Coetzee admitted, “I can’t say I know them well.” He has never visited Mallorca at all. The locations have thematic significance, though, because The Pole intellectually revolves around the Polish composer Frederic Chopin, who spent a famously gloomy winter with the novelist George Sand in Mallorca.

Coetzee first studied Spanish in the early ’60s, reading the Gospel in translation, and has called the language “a revelation, Latin brought down to earth and given body and voice.” In his seventies, Coetzee directed a biannual seminar series in Argentina and curated a list of translations for El Hilo de Ariadna. His three most recent works, though written in English, have all appeared in Australia or Argentina before they’ve been released in the northern hemisphere — a conscious and political choice. “The symbolism of publishing in the South before the North is important to me,” he told El País last year. In a fancifully titled New Yorker piece, “J.M. Coetzee’s War Against Global English,” Colin Marshall, an essayist based in Seoul, provides a competent if uncritical overview of Coetzee’s ideas about English — that, as Coetzee says, it “crushes the minor languages that it finds in its path,” and that its speakers have an “uninterrogated belief that the world is as it seems to be” in their native language. Coetzee seems to believe that publishing in Spanish is a way of challenging that entitlement and the access his English readers have come to take for granted.

Coetzee has said that El polaco is truer to his own intentions for the book than The Pole, noting that Mariana Dimópulos, who translated Coetzee’s draft into Spanish, made interventions that led to considerable revisions of the text. In an interview with the Argentine newspaper Clarín, Coetzee argued that one of the failures of English — and thus of the English edition — is an inability to differentiate between formal and informal modes of address. In The Pole, which recounts a brief affair between Witold, an older pianist, and the younger, married Beatriz, this nuanced mediation of intimacy is lost in English. Witold is Polish; Beatriz is Spanish. To communicate, they must utilize their secondary English. The notion of interpretation and mistranslation is one of The Pole’s central pillars. With English, Spanish, and Polish colliding in a complex and confusing exchange, The Pole sits at a distance from author, translator, and reader — a frustrating riddle whose answer will always, in some way or another, fall short. For those who can’t read Spanish, it might be irritating to think you’re getting an echo of a novel in what is ostensibly the author’s mother tongue, but that frustration is intentional.

Much is made of Witold and Beatriz’s failures to understand each other, and the resulting push-pull of their sexual relationship. Witold is a noted interpreter of Chopin, whose “unusually dry and severe” version of the composer is distasteful to the “intelligent but not reflective” Beatriz. “I record this for you alone,” he emails Beatriz, sending her a recording of Chopin’s B minor sonata. “In English I cannot say what is in my heart, therefore I say it in music.” Beatriz listens, and finds nothing of note. Elsewhere, she is “amused by his English, with its correct grammar and faulty idioms,” and wonders what Witold’s words mean not only “in the Polish that presumably lies behind” them, but also “in reality.” All their conversations are like “coins passed back and forth in the dark,” with their true value unknown, and only guessed at. Of course, Beatriz is also self-translating all the time, so the uneasy chain goes from Polish to English to Spanish — and, in the case of The Pole, back into English for the reader, who must also necessarily wonder how Beatriz’s internal thoughts would differ in Spanish.

More engaging than the linguistic games are the couple’s arguments about Dante and Beatrice. Witold obviously has idealized Beatriz in her namesake’s image. She is his “angel of peace,” but takes offense to this characterization, protesting that he hardly knows her. Of course, Dante supposedly only met the real Beatrice twice, and she functioned more as muse than as actual lover. In that sense, the gaps between Beatriz and Witold facilitate a projection of the ideal that lets Witold completely succumb to his infatuation. Even as Beatriz moves on from Witold, he remains obsessed with her, and abandons music in favor of writing. In his will, he leaves her a series of poems written in Polish, and she pays to have them translated awkwardly into Spanish. They are not good poems, and she never asked to be written about anyway. Neatly and brutally, she dismantles Witold’s romanticism, and the dehumanization that Beatrice represented for her: “You had the whole creaking philosophical edifice of romantic love behind you, into which you slotted me,” she writes. “I had no such resources.”

While The Pole successfully interrogates mistranslation between individuals, it is blind to something Coetzee normally has an excellent grasp on: the broader power dynamics of language. Though the book takes place in Catalonia, there is almost no Catalan, which seems a missed opportunity for reckoning with a significant linguistic conflict. Under Franco, Catalan was banned from all official use, but it quickly reemerged after the restitution of democracy. The Catalan identity is decidedly separate from the Spanish, and proudly so — universities offer bilingual degrees, and the Catalonian consumer code requires that grocery labels and restaurant menus appear in Catalan (though this isn’t always the case). In 2017, protests exploded across the province after a vote to self-determine was declared illegal; in 2019, they escalated into riots after nine of the organizers of the self-determination referendum were convicted of sedition. (When I lived there, speaking Spanish in a bar in a remote mountain town would have been akin to striding in and plonking a very big gun down on the table.)

The Pole never really acknowledges its political context, robbing Beatriz of a depth that Coetzee afforded Elizabeth Costello, as well as Mrs. Curren in Age of Iron (1990), both female protagonists who think deeply about their sociopolitical context. Beatriz is a woman attuned to meaning and interpretation, and she’s married to a Catalan man. Yet the Catalan linguistic dilemma is never on her mind. In rural Mallorca, Coetzee even has a longtime housekeeper speaking Spanish instead of Mallorqui or Catalan, which would perhaps be more likely. While this absence could be intentional, furthering Coetzee’s ideas about the fallacies of language, it’s not particularly effective. You get the sense the novel could really be set anywhere, rendering The Pole particularly removed, even within a body of work that has always been characterized by alienation. At 166 pages, it’s brief, so when Coetzee fails to get to the heart of the place he is writing about, the novel becomes more of an allegory about men and women, and a study in style and philosophy, than anything else. He is, as always, a magnificently restrained and exacting writer, so it is a beautiful study — but a study nonetheless. With so much referential material, The Pole often comes off like a conversation that Coetzee is having with himself, its true meaning only fully visible to him.

This opacity clarifies the glaring irony in Coetzee’s so-called “war” against the hegemony of English, which is that Spanish is also a hegemonic language. When Coetzee takes issue with how English “crushes minor languages,” he’s ignoring the fact that Spanish has crushed many minor languages itself, wiping out Indigenous tongues all across Latin America and posing serious threat, within Spain itself, to Basque and Galician, as well as Catalan. Franco’s aim to wipe out everything but Spanish was explicitly fascist, denying non-Spanish communities self-governance and banning their languages outright. And if English speakers are arrogant, Spanish speakers can be equally so, looking down upon Latin American dialects in favor of European Spanish, or telling Catalan people to literally “speak Christian.” In discarding the world’s most successful imperial language, Coetzee has actually just gone and picked up the second most successful. You slip the chains of history and, alas, end up in a very similar prison.

It would be reductive to say that Coetzee is at his best only when he writes about his home country. Yet in his early and mid-period novels, most of which are set in South Africa or at least in an approximation of it, there is a vitality, a constrained fury, a sense of deep urgency that is absent from his later work. Even in his distrust of language, it’s clear that his writing is reactive, posed to work against a system in ways that are shocking and dynamic, utilizing violence, allegory, and history in a quest to create meaning. The Pole lacks that fierceness. It illustrates the central pitfall of Coetzee’s trademark approach, which is that silence is only radical when there is something to subvert. Incorporating Catalan could have brought something of his old mastery of language politics: peeling off nationalist propaganda to poke at what lies beneath. Instead, The Pole contents itself with reinterpreting Dante and Beatrice, and playing with ideas about mistranslation, recalling what Coetzee once wrote of Robinson Crusoe: “having pretended once to belong to history, he finds himself in the sphere of myth.” Coetzee has always danced between the two, but this interchange loses resonance in The Pole, and the author lands firmly in the treacherous territory of fairy tale.

Recently, South Africa enacted perhaps the most significant name change of its history: the major city Port Elizabeth became Gqeberha, an isiXhosa word that’s proudly difficult for Anglo tongues. “We are nobody’s colony,” said a spokesperson for the premier of the Eastern Cape, which is now allowing students to take their final high school exams in isiXhosa and Sotho — a small but important step. In a country that teems with different cultures and languages, the problem has always been one of articulation. Afrikaans and English can only capture so much of the full picture.

For Coetzee, the way to poke at this shortcoming was to turn away from language, toward silences and distances, and to hope that truth could shine between the words. It’s an approach that worked in the past, but would probably not work now — the country, whatever its problems, is no longer a prison, and its literature need not resemble dispatches from behind bars. It’s far past time for the narrative of South Africa to evolve beyond white guilt. New writers are taking different approaches, embracing language in joyful, emotional ways, while writers of Coetzee’s generation, like Miriam Tlali and Zakes Mda — a prolific poet and playwright who only published his first novel after the end of apartheid — are being considered anew. (Both Tlali and Mda, though brilliant authors, were never lauded on quite the same level as Coetzee, perhaps for their refusal to compromise to European audiences: “Our duty is to write for our people and about them,” Tlali explained in 1984.) Elsewhere, work from older writers, like Alex La Guma and Peter Abrahams, has been recently reissued — evidence of a rich literary culture that goes far beyond Coetzee.

In Magogodi oaMphela Makhene’s Innards, released this year, speech and dialect — Tswana, Sesotho, isiZulu, Afrikaans, English — are used to brilliant effect. The work of South Africa’s latest Booker winner, Damon Galgut, is theatrical, lyrical, and boldly queer in a way that differentiates him from Coetzee entirely. Coetzee, in the last few years, has increasingly little to say about new South African writing, and he was never overly forthcoming in the first place. Twenty years on, it’s possible he’s ceased to be the ultimate authority, a position he never seemed fond of.

As more and more writers grow up without the direct memory of apartheid, stories will change. “Now the author is dead,” Zakes Mda said in a 1997 interview, “and the author was apartheid.” For so long, the regime had been a factory of “ready-made stories,” as he put it, an era in which, he observed in a 2002 interview, “there were no gray areas.” Now the whole country is a gray area — a country of rolling electrical blackouts and widespread government corruption and terrible droughts, but also of ambition and sharp, dry humor. It is a place that I don’t think Coetzee knows very well anymore — miles removed, I hope, from the country where he once put his ear to the door and heard Bach telling him that better things were out there. Perhaps one of the best things you can say about Coetzee’s work is that it’s not as true as it used to be; that one day it will appear to readers as text from a very long time ago, written in a strange, dusty language that nobody speaks.

Ella Fox-Martens is a writer living in London.