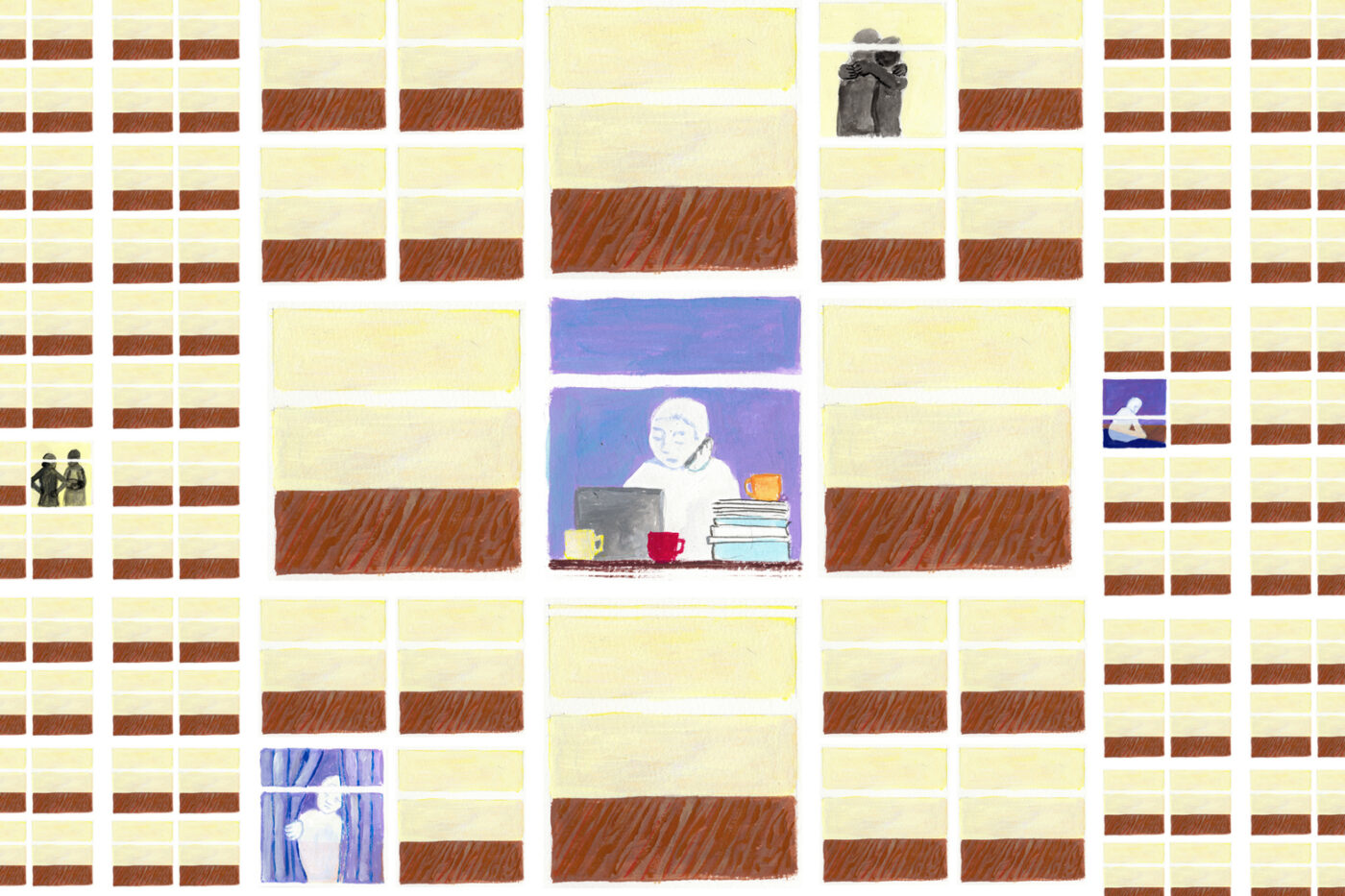

Illustration by Bix Archer

Illustration by Bix Archer

It’s no secret that the profound losses and disruptions to daily life of the past year have had a major emotional and psychological impact on nearly all of us. Many of the effects are obvious — loneliness, grief, disorientation, anxiety — and yet, aside from a profusion of dubious self-care tips and misused therapeutic language on social media, we have barely begun to reckon with their enormity and complexity, not to mention the long-term individual and cultural consequences.

We asked mental health practitioners, students, patients, writers, and thinkers for their insights into the state of our mental health, just over a year into the pandemic.

A year before Covid first appeared on our shores, “burnout” was already having a moment. In January 2019, then-Buzzfeed culture reporter Anne Helen Peterson presented a unified theory of millennial lassitude. Our tendency to put off errands and shrink from bureaucratic tasks like health care reimbursement was not evidence of coddling, but of a more existential crisis — burnout — resulting from the idea that we “should be working all the time,” promulgated by “everything and everyone.” Burnout, in other words, was a necessary byproduct of capitalism, compounded among the young by the system’s diminishing returns. However degraded, Peterson’s burnout is recognizable as a descendent of Marx’s “estranged labor” — in which the worker “does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind” — updated for an era of financialization and shoehorned uneasily into a simplistic generational frame. Five months after her essay went viral, the World Health Organization announced that burnout would be included in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases as an “occupational phenomenon” resulting from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” and characterized in part by “reduced professional efficacy.” This competing definition rejected even rudimentary anti-capitalist critique: according to the WHO, burnout is chiefly a failure of personal management, significant to the degree that it imperils workplace productivity. It “should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life.”

The pandemic has vastly increased the term’s ubiquity, neutralizing, in the process, whatever consciousness-raising potential it may once have had. Back in March 2020, when many in the West had barely begun acclimating to the Covid crisis, the BBC’s “Worklife” vertical promised to advise readers “How to avoid burnout in a pandemic.” Whether the source of their stress and anxiety was adjusting to remote work, the sudden burden of round-the-clock childcare, or decision fatigue in the face of rapidly shifting public health guidelines, the prescription was basically the same: self-care. “People need to find things that work for them,” the column urged, “whether it’s meditation, solitary walks or bingeing on Netflix.” This early advice came to be representative of the genre, whether the alleged burnout sufferers were home-based knowledge workers struggling to establish boundaries; traumatized health-care workers in understaffed hospitals; essential workers whose newly exalted status came with no guarantee of increased wages or PPE; or people caring for elderly family members without the usual support systems. It seemed there was no one to whom the rubric burnout could not be applied. Weep for the junior investment bankers of America! Robbed of the chance to form lucrative relationships in the office, they’ve had to content themselves with $20,000 “lifestyle allowances.”

Burnout’s elasticity is not proof of its abundant meaningfulness, but the opposite. Regardless of their divergent material circumstances, it’s true that ICU nurses tending to four patients at a time and Goldman Sachs analysts working 100-hour weeks have something important in common. Here’s a hint: it isn’t a problem of personal mental health. We don’t need a neologism for exploitation, especially one designed to mystify more than it reveals. So long as burnout persists in the popular imagination as an ailment above all else, we’ll keep treating its symptoms to prolong the disease.

—Jess Bergman, editor at The Baffler and contributing writer at Jewish Currents

I started working in the child and adolescent OCD ward of a psychiatric hospital in November 2020. When I tell people this, they immediately think of OCD patients’ famous germaphobia in the context of the pandemic. “Ooh, how difficult,” my friends wince, adding that seemingly omnipresent phrase, “especially these days.” Many offer sympathy, picturing me in a unit full of teenagers who unravel at the mere mention of a runny nose. “Do your patients wipe down their groceries too?” a concerned mom once asked me.

But the kids on our unit don’t have groceries, sourdough starters, or Zoom happy hours. They don’t have opinions on double-masking or contact tracing. They don’t even have access to soap. (We keep it locked up to prevent excessive hand washing; if they want to use some after going to the bathroom, we provide a single hospital-issue medicine cup filled up halfway.) They’re afraid of feces, getting older, parasites, lead pipes, saying something racist, developing an antisocial personality disorder, buying new clothes, and becoming dumb. After several months, I got used to what my coworkers call the OCD paradox: the rituals that our residents believe will keep them safe are the very same ones that end up trapping them. So desperate are they to keep something out of their lives that they end up creating the exact conditions to welcome it in. For example, one resident might be so afraid of contaminating herself that she never leaves her room. Convinced that she will start sweating, that the soles of her feet will become blackened, or that some small piece of dust will stick to her forever if she even just crosses the threshold of her door, she chooses to stay in bed all day. Eventually it is her obsession with staying clean that begins to dirty her. Isolated in her room, she misses showers and forgets to change clothes, her menstrual pads remain stuck to her underwear, and her toothbrush and deodorant sit unused for months at a time in a shower caddy. Another resident is so afraid of forgetting something that he will ask you to repeat every fifth sentence. The mental effort he makes to break everyone’s speech patterns into five-sentence chunks means he has no chance of remembering the conversation as a whole. The more he asks to remember, the more he forgets. So he sits on the lip of his bed, screams into his hands, and refuses to talk to anyone.

If our residents are not afraid of Covid, our bosses certainly are. “This is what six feet looks like” signs are strung up on every wall. An Infection Control Nurse performs unannounced inspections of our unit, and writes us up for not maintaining the proper distance or wearing protective goggles. Even though most of us were vaccinated in December, we still wear surgical masks, fill out our daily online Covid attestations, and — to protect the hospital from liability — verbally confirm every time we enter the building that we have not had any coughs, fevers, or muscle aches in the past fourteen days. We go through this checklist so often that we joke it’s become a refrain in our dreams.

Some days we feel lucky we’re not working in “a real hospital,” intubating patients and praying an antibody infusion will work. On other days, we find a resident with a belt around her neck, and scramble to save her life. This is just the nature of mental health work, and, with adolescent rates of OCD skyrocketing, the pandemic has only given us more patients to treat and less time to treat them with. But while we put in more hours and take extra shifts, we remain overworked and understaffed, paid $1.65 over minimum wage, and expected to remain on our feet eight hours a day. We are at capacity; as soon as one resident leaves, another one takes her place. Our unit director says that since we’re busier now than we ever have been, she wants to start housing two kids per room — but we can’t, of course, because of Covid.

—Anonymous mental health worker, Massachusetts

Our Crisis Response Unit got up and running on April 1st, 2019. It’s a team of six civilian first responders, city employees. They’re not commissioned officers, but behavioral health specialists who are an alternative first-response, instead of the fire department or the police, to respond to individuals in crisis, often responding to cases arising from poverty or behavioral health issues or substance use or disabilities.

Last March, we were getting information just like everybody else, day by day, trying to navigate the beginning stages of the pandemic. We saw institutions around us, like the community care center, which is run by our hospital system, initially shut down or greatly modify their services often going remote or to telehealth which is hard for this population. Most of the local mental health service providers and the housing advocates kind of shut down or cut down services, too. We continued to work throughout the pandemic — we have not had a day off since it began. The number of crisis calls has increased by 30 percent in our county. The ER is flooded.

We’re really big believers that if you’re going to be an alternative first response to law enforcement, you have to be nimble and flexible, and you have to be available. I think we really did solidify ourselves as essential, and as a real alternative to the police. We were doing a lot of rides, for instance, to the methadone clinic, because the regular bus services shut down. I think it gave us a lot of credibility with the cops and with the fire department to see that, hey, while everybody else is kind of sheltering in place, there still are folks out there like the CRU team who are working.

In terms of mental health issues that we deal with in the field, the folks that we see have been getting more and more acutely mentally ill: harming themselves, or doing harm to others. Really, they are not able to take care of themselves — they’re disorganized, disoriented, not necessarily able to stay clothed or to find food or shelter. Those folks really need to be stabilized and spend some time in the hospital and maybe get back on some medications.

And we get a lot of folks who are just lonely. Maybe they’ve gotten housed, but they’ll call our dispatch and ask to talk to our team and check in with us. We do a lot more of those kinds of “phone contacts” right now, where the police dispatchers will transfer them to the CRU cell phones. We’ve also seen a lot of people really struggling to stay in recovery because their normal recovery supports are not up and running. So we’ll get folks that want to go into treatment, and we get them in, but then they’ll get discharged and we’ll get them housed and they’ll relapse really quickly. Really, truly a lot of it is due to loneliness.

The stimulus checks are pretty exciting. Sometimes what we’ve been doing is trying to find ways for them to make a plan for their stimulus check in healthy ways before they come. We absolutely noticed in the field when stimulus checks hit. A lot of people bought kind of, for lack of a better term, junker cars or RVs to live in. And we’ve definitely seen an increase in relapses around stimulus time. But then we do see other uses, like where people are planning to use their stimulus checks for a storage unit. So I think it’s just about being kind of proactive and having conversations with those folks before the stimulus checks come.

Some of the city is coming back now, and we are hopeful that some of the other service providers are moving into more of a hybrid model. A couple of our NA groups and AA groups are starting to meet again. Shelters are still doing COVID rapid-testing before you’re able to move in, but they’re more accessible than before.

I’m hoping that more groups will open up. More support groups, more AA groups, more NA groups. I’m hopeful that people can communicate without masks on and hug each other and feel like we can transport a couple of people in the car together. And they can hang out and talk as opposed to separating people because they’re not in the same household. I am hopeful with the nicer weather that people are going to be able to start to do more activities and stay in recovery. Sunshine can help.

—Anne Larsen, Outreach Services Coordinator, Olympia Police Department, Olympia, WA (as told to The Drift)

My stomach flipped when I saw the subject line of a recent email: “Currently dying.” One of my students was asking for an extension, describing all she has been dealing with — loneliness, health problems, anxiety, death in the family, deadlines, isolation, managing two part-time jobs on top of school work. More than a year into the pandemic, my family, friends, colleagues, and online acquaintances all report feeling tired and abandoned. In a landscape of significant psychological unrest, quick mental health fixes have proliferated.

A particularly worrisome trend I have studied is the increased enthusiasm about the Artificially Intelligent Psychotherapy Chatbots, such as Woebot, which promise to provide Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT). The premise is that, through digital phenotyping — quantifying moment to moment behavior with data from personal digital devices — a chatbot will learn more about the user’s mental state, prompting her to reframe negative thoughts and steering her away from psychological traps. Chatbots have been heavily promoted during the Covid-19 pandemic, marketed as especially attractive due to their relatively low cost, convenience, and availability. Recently, the Food and Drug Administration loosened the criteria for licensing of such apps with the hope that they can help more people with the mental burdens of the pandemic.

It is wrong to call what chatbots do “therapy” or chatbots “therapists.” The word “therapy” originates in Greek. The verb form “therapeuo” means “to serve, to attend, to be servant,” and “to take care of something or someone (e.g., people, animals).” It also means “to heal, to cure” — a meaning developed in the fifth century by Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine. A transitive verb, the word itself implies multiple agents or persons participating in the process of healing or taking care. In modern psychology, medicine, and psychiatry, too, therapy has been used in a way that addresses something taking place between multiple agents.

A real therapist has training and gets to know patients, making observations about their manners of speech, affect, gestures, even silences. Chatbots, by contrast, engage with users primarily by using algorithms to detect their mental state based on the user’s written responses to prompts. The tacit assumption underlying this technology is that users are able to write out accurate descriptions of their problems. Human psychology is complex, though, and we don’t always have knowledge of our cognitive and emotional states. In the presence of a mental disorder, it may be even harder to clearly understand and articulate our feelings. The depth of a chatbot’s “understanding” or engagement with an individual’s distress is contingent on its programmer’s vision for the scope and range of mental distresses.

What is the best advice, then, for people like my student who are struggling with all the challenges exacerbated by a pandemic that keeps dragging on? Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes, despite marketing to the contrary. But, as the effectiveness of that marketing indicates, many people are suffering, and it helps to commiserate and share what we’re feeling with other people — especially those who, unlike bots, may be feeling the same ways.

—Şerife Tekin, PhD, Associate Professor of Philosophy and Medical Humanities at the University of Texas at San Antonio

The phrases “pandemic fatigue,” “burnout,” and “loneliness” fail to capture the pain I’ve witnessed in my capacity as a caregiver over the past twelve months. I’ve often found myself at a loss, attempting to do remote phone sessions with clients on their bus commutes home from work or with their relatives in the background. We often think about trauma today through the lens of post-traumatic stress disorder — symptoms typically include hypervigilance, flashbacks, avoidance, and nightmares in response to a single event. It’s a deeply limited diagnosis, and it rarely applies to the kind of client I see. My clients have usually faced multiple traumatic events, layered and concurrent — things like child welfare involvement, intimate partner violence, incarceration, and homelessness. Their trauma responses involve rage, guarded attitudes, and a sense of helplessness that can be hard to penetrate as a therapist. The pandemic has itself been traumatizing, ripping away the sense of order and routine that many of us require in order to function.

Trauma work happens in stages. The first prioritizes safety, stabilization, and trust, restoring the power and control that are stripped away by traumatizing events. Covid-19 has created an impossible feedback loop, making trauma treatment nearly impossible — there is no capacity for stabilization as deaths, exposure risks, and physical distancing continue. We are stuck in stage one.

A client who had briefly been incarcerated told me that she hoped the pandemic would help everyone better understand what it was like to be confined, limited in one’s movement and stuck with one’s thoughts. Over the past year, my clients have seen existing gaps in access to healthcare, housing, and support widen, creating newly traumatic stressors. How does one survive a highly-contagious disease on Rikers Island, where masks are in extremely short supply? How does one survive Covid within the New York City shelter system, which requires everyone to enter through several massive “assessment shelters?” Covid is a wedge, jamming into existing cracks that we could once step over or look beyond. The trauma rolls on, and the gaps widen.

—Brianna Suslovic, clinical social worker, Brooklyn

Many have noted that the pandemic is hastening some of the most depressing socio-economic trends of our time: the dominance of Amazon, the death of small business, income and health-care disparities, the decline of the arts, and more. Another trend it has accelerated is the internet’s takeover of the marketplace of advice. With the desperation of a gambler at the slots, we throw our problems into algorithms and see what answers are spat out. In the past year, professional therapists have migrated online en masse, further confounding the line between accredited counselors and Reddit trolls.

Today most counsel is crowdsourced, a turn that not only challenges the necessity of professional expertise but also brings new possibilities for collective action. People are turning to the internet for everything from racial solidarity to assistance with mental health. There are risks to this practice of scrolling for support, but in the face of sluggish federal guidance, which always lags behind the real pace of public crises, leaves people little choice. Far from a mere diffusion of political energies, virtual mutual aid like the Facebook group for long-haul Covid support or the r/unemployment Reddit community can lead to concrete assistance and even social reform.

But online advice can also feed our collective distress. All too often, self-help scrolling translates the impossible burden of contemporary risk management into the imperative of individual research, whether applying to the most secure way to vote by mail, purchasing the “greenest” products, or finding the most effective masks. The anxiety epidemic we are witnessing is a manifestation of this privatization of social stress. Anxiety is etymologically rooted in the feeling of being strangled; suffocation might be the definitive experience of the past year. As online self-help reminds us, one can be surrounded by all these choices, by so many noisy voices, and yet remain utterly alone.

—Beth Blum, Assistant Professor of English at Harvard and author of The Self-Help Compulsion

Daniel sat across from me in the examination room on the inpatient psychiatric unit. Ankles crossed, eyes fixed on a spot on the floor, he prepared himself. I hate performing intakes, asking patients about themselves and their backgrounds, in the examination room; the medical equipment and gurneys can be triggering. But it is the only private room on the unit.

While I asked my usual questions — who do you live with? Have you ever been to a place like this before? What brought you to the hospital? — Daniel started to shrink away, answering me only with nods, sheepish shrugs, and monosyllables. He wasn’t rude, but his eyes were empty.

Although Daniel is an adult, he granted me consent to speak with his mother. “He threw everything out the window!” she told me. “And we live on the ninth floor, he could have hurt someone! Our phones, chargers, shirts! I couldn’t stop him, I didn’t know what he was trying to do!” Ms. Browne broke into tears, but she continued, “I don’t know what to do anymore. He can’t go to PHP because of Covid and he was doing so well!”

PHPs, or Partial Hospitalization Programs, are for patients who cannot work due to a diagnosis or need help readjusting to life after a stay in an inpatient psychiatric unit. In PHPs, participants attend group and individual therapy as well as classes to learn coping mechanisms. These programs are vitally important for patients like Daniel, offering structure, community, and a calming sense of routine. If a patient does start to decompensate, staff members are around to identify the problem and treat it. Covid-19 has pushed PHPs online, and, as a result, many patients stop taking their medications and end up in manic situations — as Daniel did.

Already exhausted from moving himself through the process of admittance to an inpatient psychiatric unit, Daniel would be given medication, seen by his psychiatrist, and discharged back to a telephonic program. I worry about patients like Daniel on a daily basis; until PHPs return, they will keep having emergencies and coming back.

—Anonymous social worker (Names have been fictionalized to protect the patient’s privacy)

Zoom has dominated most pandemic workplaces, but as a psychiatrist my year has been shaped by the telephone. While some patients have no issues using video conferencing for our appointments, the majority of my caseload prefers not to appear on screen. I have never met most of my patients in person, and I have no idea what the majority of them look like.

There are some undeniable upsides to telehealth: patients who were too paranoid, too confused, or too depressed to come to the clinic in person now “see me” regularly over the telephone. Those with agoraphobia can now get phone therapy without needing to overcome their illness in order to make it to an appointment.

In other ways, the quality of care suffers. My homeless patients have no home to take calls in and thus no privacy, and so a patient with schizophrenia talks to me about her fecal incontinence on the bus. Getting electronics involved can also worsen paranoia. Some patients find the phone untrustworthy because “they might be listening” — which, you know, fair enough. I jump at any opportunity to see patients in person, and make a point to visit when any of them shows up in the ER when I’m working. Unsurprisingly, it becomes clear in person that many have been struggling much more than I ever imagined.

Hospital administrators tell us that telehealth is here to stay, and given its undeniable convenience I can see why. But I chose this career out of a desire to connect with people. I have to wonder whether I’ll ever again get what I signed up for.

—Andy Hyatt, psychiatry resident, Boston

Almost everyone spent too much time on the computer during the pandemic: feeling awkward and self-conscious in Zoom meetings, and then, later in the evening, at Zoom drinks; arguing; lying; scolding; decrying the scolds; over-sharing; spreading conspiracy theories; broadcasting evidence of breaking lockdown rules to “close friends”; and seeking advice from Instagram influencers who call themselves things like “The Millennial Therapist”.

A certain style of grandiose and superficially authoritative language seems to have proliferated on social media. I saw a good (and telling) example recently: a post shared a joke about a theoretical landlord who might use the language of “boundary violations” to evict someone. The person who retweeted the joke did so with a comment like: “This actually reminds me of my former roommate, who used this type of therapy language to excuse their objectively unacceptable and emotionally abusive behavior during lockdown.”

There are so many things to parse in a post like this: it refers obliquely to a person who is intended to see it (but is not really allowed to reply); it implies that the author of the post is able to assess events she was involved in objectively (or, even more troublingly, that her version of events simply is the objective standard); and it does the very thing the author is condemning, using therapy language (“abusive”) to excuse passive aggressive subtweeting.

The rise of this language is related to what has been called “Instagram Therapy,” a term that refers to the dissemination of actual mental health advice through social media — the typical symptoms of ADHD or BPD, for instance, detailed in a pastel infographic on Instagram. But where that kind of thing can improve access to information (especially for groups often excluded from mental health services), using psychological vocabulary to complain about a “ro*mmate” does not democratize information — it actually does the opposite.

A phrase like “boundary violation” or “emotionally abusive” can make something sound like a grave transgression, but could mean a lot of things, many of which may not sound quite so grave described in plain terms. In the wildly popular book Conflict is Not Abuse, Sarah Schulman argues against this tendency to exaggerate the gravity of events. She notes that, in the current cultural climate, assuming victimhood is an easy route to being treated with sympathy, which encourages the widespread practice of, as she puts it, “overstating harm.”

Therapy phrases seem to come from nowhere, and then are suddenly ubiquitous. “Accountability” is the latest fad, and I will admit I don’t know what it means. (I tried to look it up and just found a lot of blog posts about “accountability in the workplace” and managing your workload.) Words like “toxic,” “harm,” and “gaslighting” have been around for a while — remember when Donald Trump was gaslighting America? — and some of them seem to have come full circle and become offensive. Just last week, I saw someone post that using “gaslighting” colloquially minimizes the seriousness of real gaslighting. My problem is more that these words seem like a way to describe events and interactions with precision and clarity, but have instead added a layer of obfuscation and confusion at a time when socializing is already fraught.

—Rachel Connolly, writer, London

In a turbulent time marked by difficult weather circumstances and foreign market policy changes under Trump, Covid-19 has been an additional source of stress for the farmers I know through AgriWellness (a nonprofit that promotes behavioral health services among agricultural populations). Recent federal relief payments weren’t distributed equally — they benefited the large farmers much more than the small operators. You put those things together, and Covid significantly complicated their decision-making. Farming has always been a career, or a way of life, that has involved the capacity to endure isolation and to rely on your own decision-making skills.

Covid complicated farmers’ social interactions, too. I know that a number of coffee groups that meet mostly during the winter months had to stop meeting. One group that I know of met every Monday morning to discuss magazine articles dealing with behavioral issues, farm stress, and other relevant topics. They had to stop meeting in March when two of the usual members came down with Covid, and they haven’t met since. I think they’re probably getting closer to returning now that the number of vaccinations has risen.

I have found that Covid has increased farmers’ openness to talking about behavioral health problems. My sense was confirmed by a recent poll done by the American Farm Bureau Federation, showing that the agriculture worker population sampled is even more open to seeking mental health assistance when needed, and better understands the signs and symptoms of stress, than they did when they were surveyed in 2019.

We in rural communities have found that farmers need telephone hotlines and helplines that are confidential and staffed by counselors who understand agriculture. That provision is one of the recommendations of the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (a new, federally-funded network of behavioral health services). We found that follow-up counseling was particularly beneficial, as are community workshops between the business and agricultural communities But I think there needs to be more efforts to reach the farm worker population — that’s going to take some work. I would expect California, Arizona, Oregon, Washington, Florida, and Texas to all be involved in improving the access to agricultural workers, whether they are migrants or permanent workers.

We know that farm stress is never going to go away, and we know that farmers can’t control the weather or climate change, and we know that they can’t have much or any influence over federal policies that affect the sale of agricultural products. They can’t control disease outbreaks in crops or livestock, or even Covid in farm people. One of the few factors they can have control over is how they manage their behavior. Most of us are getting older, but I think the next generation is taking this on. I’m seeing a lot of young psychologists, veterinarians, agronomists, financiers who are interested in figuring out how to better detect stresses in the farm population, and what we can do about that. There’s been, I think, considerable improvement in the level of assistance that’s available to farmers, ranchers, and so forth. We’re just at the beginning of a surge of improvements in understanding and coping in the agricultural population.

—Mike Rosmann, psychologist, farmer, and executive director of AgriWellness, an organization that promotes behavioral health among agricultural communities, Harlan, Iowa (as told to Elena Saavedra Buckley)

For a time in college, a friend of mine used a psychic as a shrink. The rationale was partly economic and mostly a joke: sessions clocked in at $50 a reading — $30 with a Groupon — and the psychic was actually named Sabrina. But there was a mild emotional honesty to it; Sabrina read what she wanted to hear, told her exactly what to do (date a man with the initials J. L., for one), and delivered vague dispatches from long-dead cousins, all with an unwavering confidence and divine authority. This friend hasn’t seen a psychic in a while, but the impulses that led her there — a basic desire for comfort, a low-grade cynicism about American healthcare, a shortage of funds — were widespread before the pandemic and have only intensified since. “I might have had the best year from a work perspective than any year prior,” musical spirit reader Christopher Allan said, “because of how many people were seeking guidance in that spiritual realm.”

Allan hails from Long Island, which he describes as “the breeding ground for American mediums.” Theresa Caputo, George Anderson, John Edward — “Everybody who is anybody comes from the area,” psychically speaking. “It’s a little more spiritually open, compared to the country,” he said. In part because of Long Island’s status as a clairvoyant incubator, clients had been coming to Allan from around the world — Dubai, South Africa, France — so long before lockdown, he’d already established less physical modes of accessing energy (Skype). “I embrace the virtual realm,” he said. “Energy is energy. It has no physical boundaries or limitations.” After socializing got distant, he transitioned fully to video readings. One perk, he said, is that clients can record their sessions as souvenirs; also, he doesn’t need to wear pants.

Like Allan, psychic Laura Colavito-Agosta saw an influx of interest after lockdown; unlike him, she stopped seeing clients, relying instead on her shop and husband for income — an approach she had used after 9/11. When the towers fell not far from her store, she turned away prospective patients. “I didn’t think that it would be in my clients’ best interest to read them,” she said. “Making them hopeful at such a devastating time — or if a question doesn’t come through — I don’t think that’s fair. I don’t think that’s right.”

Primary Metaphysician Corbie Mitleid, who speaks in a style she calls “New York fast,” saw her role more pragmatically. In her “thirty-second elevator speech,” she tells clients that she’s been in the business for 48 years; it’s her full-time job; before Covid, she traveled 45 weekends a year; her nickname among friends was “the Travel Channel.” Like Allan, Mitleid had always seen some customers distantly, but during the pandemic, she talked to everyone by phone, Skype, Zoom. The questions they asked, she said, were not so different from the normal ones. “It was love. It was career. It was finances,” she said. “But the underlying fear in the voices was palpable. You could hear the hesitation. You could hear with some of them that they were very close to tears. You could hear the breathing, the faster breathing. They were terrified. What I would do is I would say: Breathe. Right now, where you are, you are safe.”

All three understood their work to fall somewhere between spiritualism and self-help (and possibly, some skeptics might add, a touch of scam). Allan said his sixth sense manifests as an affinity for story-telling, spinning a narrative about a dead person’s life and what comes after it, stitched together by personal details like birthdays, names, and how they died. Mitleid operates more like an executive recruiter — which, incidentally, she also used to be. “Now, I’m not a fortune teller. I am an intuitive consultant,” she said.” I search for your opportunities and how to grab them: here’s the tough stuff; here’s how to get through it or around it; here’s your toolbox — go rock n’ roll.” Clients needed to understand that they had choices, she said, that the pandemic was “not the end of the world,” so much as “basically Mother Nature marching us into the corner and giving us a time out because we were not listening.”

The last time a deadly global pandemic sent the world inside for a year, Americans were just emerging from a decades-long spike in occultist curiosity. The combined death toll of world war and influenza renewed interest in the waning Spiritualist movement of the 1890s, specifically in communing with the dead. A New York Sun headline from 1920 summed up the spirit: “Riddle of Life Hereafter Draws World’s Attention.” Newspapers serially published books like “Life After Death: Do The Dead Communicate With the Living?” Ouija board sales took off. Longtime mystic sympathizer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle became a dedicated ghost hunter following his son’s death in combat. (Perhaps because of the war, the most vocal ghosts then seemed to be men: “The female spirits, if there are such,” one Hartford Courant article grumbled, are “as dumb as oysters, which, it will be conceded, is a great departure from their earthly habit.”) The results of conjuring ghosts were at once comforting and impotent, a reporter at the New York Tribune surmised. “They tell us that dying is not a painful process,” he wrote, conceding some adjustment to the post-corporeal realm was inevitable. “Finally,” he added, “they all say that in no circumstances would they come back.”

—Tarpley Hitt, writer and editor at The Drift