Mentions | Issue 2

The Entire History of the Louisiana Purchase (1997) |

FILM

People from New Mexico rarely let themselves off the hook for making art about New Mexico. Joshua Oppenheimer, the director of The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, partially grew up in Santa Fe, a city dedicated to selling the state to outsiders. This film mixes archival footage with the fictional story of a woman living near the Trinity Site, where the atomic bomb — the doing of a different Oppenheimer — was? first detonated. She believes her baby to have been immaculately conceived, before deciding it’s the second coming of Lucifer. She kills it in the microwave. Oppenheimer’s work, like Kubrick’s, considers the overwhelming legacy of the genocide of Indigenous people in North America: blood pours out of the microwave as if from the Overlook Hotel elevator.

E. S. B.

“DVD Menu” |

SONG

Anchored by Rob Moose’s gravelly violin, the spacious little instrumental intro to Phoebe Bridger’s Punisher, could easily work as a prestige-TV theme song. But as its title suggests, “DVD Menu” will also take 20th-century babies back to those pre-Netflix nights where you’d pop in the disc and go make popcorn as a thirty-second snippet of the film’s soundtrack repeats, repeats, and slowly sinks into your nightmares.

T.P.

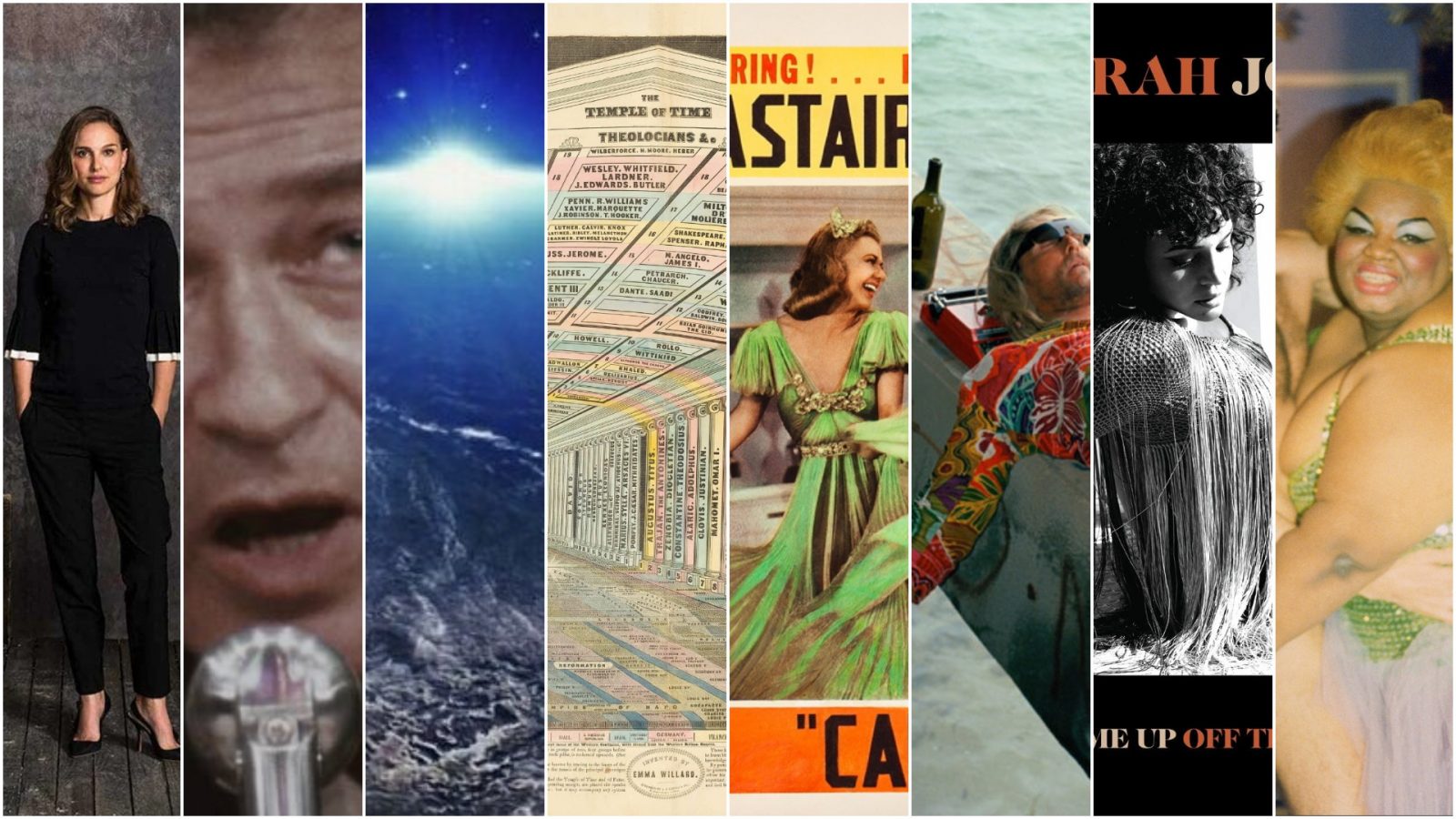

The Beach Bum |

FILM

Is it possible for a single movie to eliminate every positive feeling you have toward a director?

B.B.

Reptile Facebook Groups |

LIZARD PEOPLE

A scene where the harshness of the reptilian world — where dinner means live rats, not Purina — clashes absurdly with the infantilized mewling of pet culture. Photos of grass snakes draped on school-aged kids appear alongside screeds against faulty gecko deliveries and the rotting, ulcerated nodules of S.F.D. (Snake Fungal Disease). Some groups are highly specialized. Try Reptile and Amphibian Bioactive Setups for how-tos on low-maintenance enclosures; DIY Terrariums for help with hydro rocks or fake moss bundles; or Rehome your unwanted reptiles here for giving up. But most are social spaces to mingle, gossip, and swap tips on things like “field herping.” Facebook may have gotten older, conservative, and conspiratorial (look no further than South Dakota Reptiles to find QAnon’s trace on the platform’s collective psyche), but the internet’s tendency toward monoculture yields many rabbit holes. Some people just care about Malagasy leaf-nosed snakes.

T.H.

Reds (1981) |

FILM

“You don’t rewrite my writing!” John Reed says twice in Reds: first to one of his New York editors, Peter Van Wherry; and then, a couple of cinematic hours and several historical years later, to Grigory Zinoviev, one of the seven members of the first Soviet Politburo.Van Wherry is a fictional character, and, played by Gene Hackman, he stands in for any gin-soaked hack the world over — they fuck with your copy because they can. Zinoviev, played by actual writer Jerzy Kosinski, rewrote Reed’s address to revolutionaries in Baku, changing his call for international class war to a call for holy war against the American infidel: don’t go into politics if you don’t want your copy fucked with. (Zinoviev was executed by Stalin in 1936 after the Trial of the Sixteen.) In between these episodes of nonconsensual editing, we witness the love affair of Reed and Louise Bryant — a passion hashed out between Warren Beatty and Diane Keaton across typewriters, where lovers’ quarrels over which line to put in the lede lead straight to the bedroom. It’s safe to say that Hollywood will never produce another epic on the joys and pains of freelancing and leftism quite so lavish. Also featuring Jack Nicholson, as Eugene O’Neill, Reed’s friend who had an affair with Bryant, and apparently never entered a room without asking, “Where’s the whiskey?”

C.L.

Emma Willard’s Maps of Time |

ART

Mesmerizing illustrations of time, if you can get past the fine-with-genocide brand of nationalism woven through Willard’s renderings of American “manifest destiny.” Modern visual timelines — screentime apps, work calendars, and more recently, Covid-19 mortality charts — tend to be suffocating and dimensionless; Willard’s chronologically-constructed rivers, valleys, and temples, give time space to breathe.

J.K.

Natalie Portman’s Master Class |

ACTING!

I learned that shuffling the stuff around on every surface in a room shows people that you’re very upset.

T.P.

Blue Circle’s Classic Norwegian Roasted Salmon |

FOOD

The fish is impressively sculpted into an almost perfect, believably salmon-colored, rectangular prism. With wild salmon in their final century of existence, one can rest easy knowing that we’ve perfected the industrial salmon product to replace them. A product that briefly swims, eats, lives, and dies so that it can become the ideal pinkish-monolith for Whole Foods shoppers everywhere.

J.K.

Nomadland (2020) |

FILM

As Fern, Hollywood’s foremost no-nonsense thespian Frances McDormand tootles around the West living in her cargo van-slash-home. This feature captures the tension between the evasion of normal life obligations and the pursuit of freedom en plein air, but glosses over political realities — the circumstances behind why McDormand and so many others are working at Amazon on New Year’s Eve, for example. The seasonal hustle rewards these independent contractors with money, flexibility, and time to experience many sherbet sunsets. Major images include five-gallon buckets for bodily functions and McDormand’s fatigue-crinkled visage beneath the moody skyline.

E.S.

#APSTogether |

SOCIAL DISTANCE

Online read-alongs hosted by A Public Space: a brilliant writer holds our hands through 12-15 pages per week. Yiyun Li with War and Peace, Garth Greenwell with A Turn of the Screw, Ed Park with True Grit. If reading in public is “sacral,” “romantic,” and “the private self made public,” as LitHub would have us believe, then close reading in public must be bondage-slash-exhibitionism.

T.A.

The Blacklist |

TV

Imagine the most entertaining Nicolas Cage movie you’ve ever seen stretched over seven seasons (so far) of network television. And instead of Cage it’s James Spader, not so much chewing the scenery as gnashing it to bits with unhinged exuberance. The writers’ flourishes constantly threaten to send things off the rails, but they ultimately stick to soothingly predictable recipes, like the Great British Baking Show reconceived by Dan Brown. Also the soundtrack is really good for some reason.

E.B.

4 3 2 1 (2017) |

NOVEL

What’s better than one Bildungsroman? For Paul Auster, the answer is four. If you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to grow up Jewish in New Jersey in the decades following WWII, and you’re sick of Philip Roth, then count yourself lucky. Now, you can immerse yourself in that world not once, not twice, but four times in a book the length of four books.

I.A.

Carefree (1938) |

FILM

Fred Astaire is the psychoanalyst we need but don’t deserve. A gloriously uplifting film about subconscious mind control: Ginger Rogers is manipulated by hypnosis, sedation, and, in the end, a punch to the head. Includes the irresistibly senseless musical number “The Yam.”

B.H.

Roasted Watermelon |

FOOD

An attractive vegan YouTuber said roasted-then-smoked watermelon “looks just like meat,” so I tried it out. The result looked vaguely pot roastish, like red meat with a dark glaze. But the illusion only deceived one of the five senses. For the first half of a bite, the desiccated fruit’s rubbery texture was uncannily flesh-like, but each mouthful finished with a slight crunch that can only be grown on a vine. I left the table confused, and determined to no longer cook across Aristotelian categories. All in all, much less tasty than a fresh watermelon.

J.P.

Desperate Living (1977) |

FILM

There’s something unnervingly topical about watching a character in the throes of a mental breakdown find her calling as the henchman to a dictatorial queen hell-bent on infecting her subjects with rabies. John Waters has always been prophetic.

I.A.

William Gass’s Hatred |

AFFECT

In an interview with The Paris Review in 1977, William Gass poses the hypothetical question “Why do you write?” and answers: “I write because I hate. A lot. Hard.” Each of his three major novels deals with characters coming to terms with their distaste for the world. In Omensetter’s Luck (1966) a preacher subjects his parish to his suffering, concealing his atheism and daydreaming about how Jesus urinated. In The Tunnel (1995) a Nazi-obsessed professor hates his wife and reflects on being the child of an alcoholic and getting swept up by the energy of Kristallnacht. In Middle C (2013), a music professor specializing in Schoenberg builds an Inhumanity Museum in his attic showcasing newspaper clippings of human atrocities, and perpetually rewrites the sentence: “The fear that the human race might not survive has been replaced by the fear that it will endure.” These are familiar attitudes for Gass. In the afterword to Omensetter’s Luck, he says of the years he spent writing it: “I didn’t much like my life. I didn’t much like my job. I didn’t much like the world.”

J.W.

Pick Me Up Off the Floor |

MUSIC

Norah Jones’s new album — how do you judge something so tied to the absolute high of your first Vanilla Bean Crème Frappuccino? The new songs are totally 100% just fine.

B.L.

John Woo’s Unashed Cigarettes |

PROPS

Hong Kong director John Woo, pioneer of the neo-noir action genre Heroic Bloodshed, is a master of the “cool guy” trope. His men ooze indifference, privilege male friendship over the allure of the female lead, tend to go rogue, etc. That decided lack of care contrasts with the hyper-stylized construction of Woo’s scenes. One example: characters rarely ash their cigarettes. Smokers go around with these comically long, curved ashes at the ends of their cigarettes, sometimes almost as extended as the unsmoked cigarette itself. But we never see the ash collapse. It always stays in place, like Tom Cruise’s hair in the Mission Impossible films, the second installment of which Woo would go on to direct. Unfortunately, when I tried this, I got ash all over myself. Not very cool.

W.L.

Town Bloody Hall (1971) |

FILM

About 50 minutes into DA Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus’s documentary about a famed panel discussion on feminism, Germaine Greer tells Diana Trilling: “I adopt the same approach to Freud as you do. I quote him where it suits me and I don’t where it doesn’t.” Norman Mailer is moderating. He doesn’t laugh, which doesn’t matter, since he’s not in on the joke. An audience member is escorted out for not paying the entrance fee; on the way out, she yells: “Women’s Lib is for rich bitches only. Germaine Greer, you’re a traitor! All of you are traitors!” By the time the 85 minutes are up, I have forgotten Norman Mailer exists.

R.B.

Whose Line Is It Anyway, season 15 |

TV

There should be a special Emmy awarded solely to whomever decided to replace Drew Carey with Aisha Tyler. No longer encumbered by the Brad Shelton of improv comedy, Whose Line… is now an escapist romp of dad jokes, prop humor, and the seemingly limitless talents of Wayne Brady.

I.A.

How to Behave in a Crowd |

NOVEL

An almost-young adult realizing that most adults, no matter their age, are still young adults. The plot of Camille Bordas’s first English book is plotless in the best of ways: preteen hero, Isidore, loses his father; while his genius siblings escape through endless PhD work, Isidore learns lessons in sex, friendship, and the German language. One of those rare books where the saddest lines are the funniest, and the funniest are the most true . “I had no choice but to be different,” Isidore tells us. “I wasn’t as smart or as good-looking as my brothers and sisters.”

D.A.

The Lobby |

FILM

A character called Old White Male extols the virtues of death over dying while seated in countless lobbies in Heinz Emigholz’s latest feature. Each of these unremarkable and purgatorial spaces is filmed from improbable angles. No other new release will so accurately illustrate pandemic time.

E.S.

Mozart Symphonies Nos. 39 - 41 (2020) |

MUSIC

Here is Mozart at the wheel of a Bugatti: Riccardo Minasi and Ensemble Resonanz take us on a near-manic peek-a-boo thrill ride. Maybe a little too zeitgeisty, but with so many surprises, a genuine blast awaits Mozart veterans; for newbies, what an ace welcome.

F.R.

Darling (1965) |

FILM

If you’re a culture enjoyer who manages not to deduce your morals from works of art, come sit by me. Let’s watch Julie Christie wear great skirts in Mod London, flirt with Catholicism, and gulp dumb bitch juice for about two hours, but (not really a spoiler) become a princess in the end anyway. She won Best Actress for this through the opposite of whatever value system got try-hard Natalie Portman the Oscar for Black Swan.

K.V.

Belhaven Scottish Oat Stout |

BEVERAGE

Thick, strong, earthy. Nutritional enough to replace any meal (ideally breakfast). Perfect lockdown drinking.

B.H.

All That Heaven Allows (1955)/ Far From Heaven (2002) |

DOUBLE FEATURE

Some grimace at the word melodrama, and to them I say: begone, heartless trolls. Douglas Sirk made this perfect 1955 film starring Rock Hudson in flannels and Jane Wyman in pretty coats. In 2002, Todd Haynes reimagined the story, this time featuring a blonde(r) Julianne Moore in 1950s Connecticut. For Haynes, as for Sirk, political virtue — a belief in an equitable and fair world for all — is uncorrupted because it’s never something signaled for personal gain; instead, it’s held onto as a source of hope in a world that is otherwise crumbling. It’s nice, once in a while, to spend three hours in the company of people who know how to live.

R.B.

NatGeo |

TV

If you’re looking for a break from this increasingly burnt Earth, Disney’s recent acquisition offers a lineup of streamable content set on an Earth-like planet sans ecological collapse, depicted in high-saturation colors and populated by erstwhile celebrities like Katie Couric and Joseph Fiennes. A good option if you can’t shell out the 90K for the NatGeo private jet tour.

J.K.

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History |

BOOK

There’s something equal parts cathartic and masochistic about lugging a 546-page book about the deadliest pandemic in history around in your tote bag during a modern-day pandemic. John M. Barry’s expansive but gripping story contains familiar details: mass death, government ineptitude, the politicking of science, and pervasive conspiracy theories. But, importantly, it also comes to an end.

A.T.

Lovers Rock (2020) |

FILM

Dance party FOMO abounds in the second episode of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe trilogy. Essentially just a single shindig recorded for an hour, this concise yet unhurried movie revives the joys of communal singing, an activity found nowhere now but the church. Indeed, the reveler’s sultry rendition of “Silly Games” stripped of instrumentation is a borderline religious experience.

E.S.

Cappuccino (.fm) |

AUDIO

An app that lets users share short audio segments called “beans,” which are collected and delivered as a morning “cappuccino.” Charmingly earnest, free-for-now, and evidence for my theory that podcasts are attractive largely because they repel loneliness. Here, for zero Patreon dollars, I can hear from my actual friends.