Mentions | Issue 9

Straight Line Crazy |

PLAY

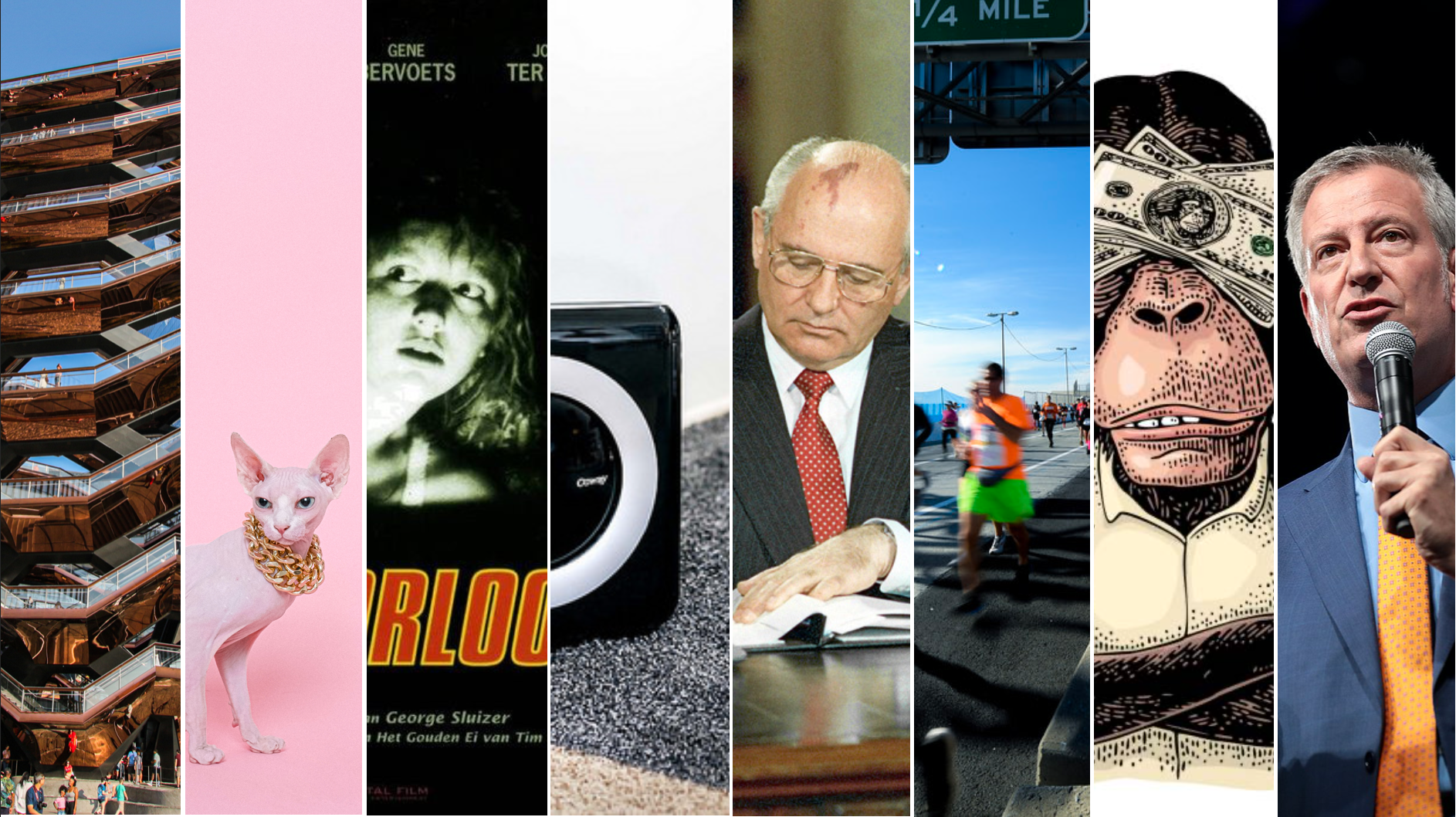

It’s not an indictment of New York City, necessarily, that Robert Moses built everything from the FDR Drive to the Central Park Zoo with both Herculean corruption and total disregard for the welfare of working-class people. Nor is the fact that Hudson Yards, the corporate mall complex where people literally go to kill themselves, was built in the heart of Manhattan. The fact that this play — a 150-minute Moses caricature complete with barely disguised British accents, a script that reads like an A.P. U.S. History extra credit assignment, and Jane Jacobs breaking the fourth wall to say, “I’m Jane Jacobs” — was put on at Hudson Yards, and that some people are paying $2,000 to see it? Now that’s an indictment of New York City.

E.S.B., K.V., & R.P.

Laila Gohar’s tableware universe |

INANITY

Perhaps thanks to social media, where the way that something photographs is more important than how it tastes, Laila Gohar became an in-demand caterer for people who don’t eat. She assembles dopey mounds of loose marshmallows and startlingly queasy shellfish topiaries, mostly for high-end brand activations, and has received slavering acclaim from a credulous fashion press corps desperate for levity. There’s a light flavor in her work of Les Dîners de Gala, Salvador Dalí’s bonkers 1973 cookbook (crayfish topiaries figure prominently), except the surrealist didn’t prescribe life-sized butter ears. Depending on your tolerance for whimsy, Gohar’s installations either amplify the artful pleasures of nature’s endless bounty or tease out a compelling argument for a wealth tax. When the pandemic forced the luxury sector to momentarily stop throwing parties for itself, Gohar cannily conceived an alternate revenue stream in “Gohar World,” a “tableware universe” — read: online shop — where you too can avail yourself of cotton napkins with dangling pearls shaped like chicken feet and trompe l’oeil candles resembling sweaty wedges of Gruyère (essentially, handsome gags). But in a way, convincing our most image-anxious industries to pay you to arrange boiled potatoes for dinner parties is the best joke of all.

M.L.

Gorbachev. Heaven |

FILM

In the first scene of Vitaly Mansky’s 2020 documentary, an 88-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev watches clips on his computer of his younger self — standing with Ronald Reagan at the Reykjavík summit, listening to Shimon Peres call him “a man who has changed history forever” — until he falls asleep at the keys. Mansky, a long-time acquaintance of his subject, renders a domestic portrait of the man once loved and hated by millions, now never without the walking frame on which he leans unsteadily and wide-eyed. There is, thankfully, no newsreel footage; the film does not try to teach us anything. It is, rather, a portrait of aging: the last General Secretary of the Communist Party tells rambling stories and bursts into songs his mother taught him. Towards the end, he watches Putin on television speak sternly of selflessness and generosity in a New Year’s address. Gorbachev seems tired and unmoved. When his hearing aid falls out, he is in no hurry to put it back in.

H.T.

Whereabouts |

NOVEL

Although Jhumpa Lahiri’s protagonist is a writer, we never see her write — until she starts walking her friends’ dog. “Our walks together thrust me forward, and though he pulls me, I’m the one holding the leash,” she says. Shortly thereafter, she pushes herself to accept a writing grant. Animal-as-muse is a familiar trope: Sylvia Plath’s “rare, random descent” of inspiration came as a black rook; Lahiri finds it in the pull of a dog in need of a pee.

I.R.

Titanique |

THEATER

No joke is too stupid, too crude, or too deranged for this musical adaptation of Titanic, which employs a campy Celine Dion, played by Marla Mindelle, to narrate (and sing!) Jack and Rose’s tragic love story in the Chelsea basement of a former Gristedes. It’s pointless to try to make sense of why this bizarre pop-culture medley — featuring a botched Dion-style Quebecois accent, Jack’s ambiguous sexuality, and reality-T.V. personality Frankie Grande (half-brother of Ariana) as both the captain of the ship and Luigi from Mario Kart — works. The only way to stay afloat is to heed the wisdom sung by Dion herself: “That’s the way it is.”

B.H.

Prima Facie |

THEATER

English actress Jodie Comer opens playwright Suzie Miller’s one-woman show with the élan of a frat boy describing his last Oxford-style debate: “I fire four questions like bullets… Face, shock. Utter annihilation. And the look I get. Dawning. You fucking idiot. You thought you had this.” To Comer’s Tessa, a young criminal barrister, law is a story one tells with the cadence of slam poetry. Judge and jury may as well lift scoring placards and award wigged MVPs at trial’s end. After some opening character development, the play turns didactic when Tessa is raped by a colleague. Comer describes how “the system I believed would protect me” has failed. Absent in the play is any notion that legal rot goes deeper than procedure, or that it regularly and more acutely disenfranchises those without law degrees. Comer’s final speech evinces just how little Miller has to say: “All I know is that somewhere. Sometime. Somehow. Something has to change.”

A.D.

r/LinkedInLunatics |

FORUM

“While Russia is taking over Ukraine,” one screenshotted user writes, “we’re taking over the Amazon event industry.” Another posts an opening for a “junior wife,” with three years of cooking experience required. As this subreddit makes clear, the professional networking site is rife with delusional posts, dubious workplace parables, absurd virtue signaling, inane inspo babble, hackneyed stabs at “disruption,” distended vanity titles, and even, paradoxically, the #nsfw. We’re witnessing a renaissance of careerist cringe — it seems personal brands, and their skeptics, have finally found a job.

J.M.

Leopoldstadt |

THEATER

If you’re looking to see someone who once called himself “Jew-ish” do public penance, this Tom Stoppard apologia — about a more culturally sophisticated version of the 85-year-old playwright’s own family, much of which was murdered in the Holocaust while he escaped to the U.K. as a child, and about his own youthful attempts to downplay his past and appear fully British — is for you. If you’d like to see good writing and acting on stage, post-Covid Broadway is probably not the place to go.

R.P.

EasternEuropeanMovies.com |

STREAMING

The weirdest cinematic treasures of Czech surrealism, Bulgarian folk drama, and Polish sci-fi aren’t available on HBO Max, Paramount+, or even the Criterion Channel, but would-be consumers can sate their hunger on this site that sounds like spam but isn’t. The owners — whoever they are — are as secretive as dissidents behind the Iron Curtain; what they have produced is a delectable combination of thrilling discovery and confounding subtitles (“Separate Tierra del Fuego… the subtle of the brut… slowly, with great art!”). In a streaming landscape devoid of mysteries, a lifetime membership to a quasi-legal hotbed of rare films supplied by the determinedly anonymous re-enchants spectatorship. Most importantly, it’s the only place to watch I Killed Einstein, Gentlemen.

J.S.-G.

Spoorloos (The Vanishing) |

FILM

George Sluizer’s 1988 thriller, which Stanley Kubrick supposedly called the scariest film he had seen, is, in spite of its premise, a relatable movie. Forgive me for being glib about such a plot: it follows Rex, a Dutchman who spends years searching for his girlfriend, Saskia, after she is kidnapped at a rest stop. What’s terrifying is not so much the fact of Saskia’s murder but the absurd banality of her disappearance. The story is a violent transposition of the agony of abandonment; this kind of passion can follow a death, of course, but can also accompany a breakup, a betrayal, even a casual rejection whose meaning “is precisely to be meaningless,” as Annie Ernaux has written. Kubrick himself once said that the “most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent.” I wonder how many times he was ghosted.

E.S.B.

@julesthelawyer |

TIKTOK

In her tongue-in-cheek vlogs, lawyer and self-described “famous person” Julia Romano asks brands to put her face on their billboards and her fiancé to “pay for the sins of men everywhere.” There is a devoted following for her dry, satirical monologues about her Starbucks addiction, student debt, and dream house manifestation, plus cameos from her hairless Sphynx cats. How unfortunate that her brother, Toronto Blue Jays pitcher Jordan Romano, has to live in her shadow.

S.L.

The Tracy Anderson Method |

EXERCISE

For fitness enthusiasts weary of SoulCycle’s pseudo-spiritual gibberish, Western yoga’s cringe appropriations, and Peloton instructors’ inane monologues about how much they love music, consider the Tracy Anderson Method. It has its faults: the cult following and celebrity clientele, the glamor shots of the company’s founder that accost you with each click on its website, the $4,000-6,000 price tags for luxury equipment, which include such delights as a “toxin-free supportive landing pad” and access to a “universe of original, nature-inspired choreography.” But the greatest asset of her online classes, which goes unremarked upon in Instagram ads, is that absolutely no one speaks. Tracy assumes that you can watch and copy her movements in companionable silence; only a friendly beep signals when it’s time for a new move. With Tracy, the exerciser is spared the search for deeper meaning and the pretense of wanting anything besides a nicer butt.

K.S.J.

Coway Airmega AP-1512HH Mighty |

APPLIANCE

This $229.99 air purifier, which looks like a cross between an iPod Shuffle and a toaster, has been a top pick at Wirecutter for seven years running. Since 2010, Coway has sold over fifteen million air purifiers in 60-plus countries and made more than one online reviewer “emotional.” The company claims that its product can remove 99 percent of “volatile organic compounds” and wrap every room in a “blanket of 24/7 clean air,” but what you’re really getting is the privilege of paying for the only free thing in your house (air).

Z.F.

Funny Girl |

MUSICAL

Depending how you look at it, the moral of this puzzling 1964 melodrama is either: (1) don’t let a (con)man bring you down, or (2) don’t be so successful that you drive your (con)man away. The moral of the current revival — starring the questionably literate and unquestionably annoying Lea Michele, who’s been announcing her intention to play the role of Fanny Brice, both personally and as her character on the unwatchable T.V. show Glee, her entire career — is: (1) if you declare your ambitions publicly and repeatedly, everyone will root for you to fail, and (2) if everyone’s rooting for you to fail, you have to be so constantly and fanatically flawless, so energetic, so show-stoppingly good, that no one can find anything to criticize. She is.

R.P.

Wall Street Oasis |

COMMUNITY

In 2022, a mere three percent of Harvard’s MBA class went into investment banking, many opting instead for the greener pastures of Silicon Valley, where the land is fat and weekends are reserved for unwinding, as long as you’re responsive on Slack. Yet persistent Wall Street aspirants seek refuge at Wall Street Oasis, a forum for bankers (“monkeys,” in WSO parlance) to discuss deal sleds, decry diversity quotas, and bemoan the death of white-shoe business culture. A recent post asking “Can we fucking celebrate our accomplishments here for once?” received 51 bananas.

C.S.

Bill de Blasio’s retirement |

POLITICS

It has been a bumpy adjustment to civilian life for former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. There were the brief, go-nowhere looks at runs for governor and Congress, then the frantic acquisition of academic gigs at NYU and, this fall, Harvard, where he shared a panel with the former mayor of Wrocław, Poland. He may have dyed his hair. He has not landed a job at MSNBC. He is now in the stage of political afterlife at which a disgruntled former aide feels safe calling him “childish, intellectually lazy, overconfident in his own abilities, and annoyingly condescending” in a tell-some about working with politicians. Yet a glimmer of senior-citizen hope lies on the horizon, as the honeymoon ends for de Blasio’s crypto-boosting successor, Eric Adams, whose mayoral administration has been light on policy achievements, heavy on Zero Bond appearances. Does the old progressive giraffe look better in retrospect? Brother, in this country you can be a senator at 95.

M.C.

Glenn Gould’s humming |

MUSIC

Forty years after his death, the Canadian composer and pianist remains one of classical music’s most recognizable names and one of the most technically exacting instrumentalists, period. Yet his recordings have a glaring, infamous flaw: his humming, which was guttural, atonal, and often impossible to excise, to the frustration of his audio engineers. Or was it a flaw? The critic James Wood compared Gould to The Who drummer Keith Moon, an unlikely peer not least due to the latter’s tendency to blow up toilets. The chief connection is their disruptive vocalizations, a reminder that there is a human behind the instrument.

C.M.

The Blue Notebooks |

MUSIC

British composer Max Richter has said that his second album, composed in the early weeks of 2003, was intended as “a protest album about Iraq” and “the utter futility of so much armed conflict.” Ironically, its most famous track, “On the Nature of Daylight,” has become the backdrop for dozens of fictional conflicts. It’s appeared on the soundtracks of at least ten T.V. shows and as many movies, adding an overused aura of melancholy to spaceships (Arrival), an insane asylum (Shutter Island), and Michelin-grade toro (Jiro Dreams of Sushi). Less useful to Hollywood, evidently, are the album’s stranger highlights, such as the tracks on which Tilda Swinton, accompanied by a percussive typewriter and video-game-like echo, reads aloud from Czesław Miłosz and Franz Kafka.

D.S.

Young Frankenstein bloopers |

FILM

The blooper reel is a dying art. Unlike the Avengers-style end-credit scenes served to today’s audiences, bloopers aren’t a sales pitch for the next tent-pole letdown. They are simply the cherry on top. The pinnacle of the form is from this 1974 Mel Brooks classic. Gene Wilder, playing the titular scientist, breaks easiest; his costar Cloris Leachman later said that Wilder’s episodes of hysterical laughter forced them to reshoot takes up to fifteen times. Which is even funnier when you remember that Wilder cowrote the screenplay: he’s howling at his own jokes.

D.K.

“Little Amal” in New York City |

ART

This twelve-foot-tall Syrian refugee child puppet arrived in mid-September for a breakneck nineteen-day, 42-event tour across all five boroughs. New Yorkers came out in droves to see her, but more importantly, to be seen seeing her: a work of photogenic humanitarian art paraded through the city. One afternoon in Brooklyn, Park Slope families stumbled over themselves to angle for Instagram. “Wait! Stop right there,” one mother shouted at her child. “Let me get a photo!” An unwitting reflection of the circus-like state of affairs for New York’s human asylum seekers.

E.C.

The New York City Marathon |

RACE

The slogan of the New York City Marathon is “It will move you.” What is “it”? Daylight Savings Time moved the clocks back; Google Maps moved masses onto the 4 train at 4 a.m., despite the fact that it was out of service; the Staten Island Ferry, crown jewel of the NYC transit system, moved more people than it typically does on a Sunday at 5:30 a.m. “Don’t pay attention to red lights,” the coordinator instructed the driver of the school bus to Athlete Village, which moved riders to latch their seat belts. But what’s truly moving about the marathon is the full-body experience of being buoyed along all five boroughs by a solid wall of applause from those so moved to come watch. Monday is even more sacred: no runners shall move.

A.R.

Selections from Australia’s Western Desert: From the Collection of Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield |

EXHIBITION

In 2015, Steve Martin found out that Aboriginal people in Australia’s Western Desert make good art. He read about them in The New York Times. Now he and his wife own 50-odd pieces, mixing Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri with Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. Sometimes they let other people look, too: the couple showed a selection of pieces at Gagosian in 2019, then six more at New York’s National Arts Club last autumn. Though the club is private, the exhibit was open to the public. Most visitors were tourists hoping to meet Martin, a receptionist said, though some did look at the art. Wall text explained that the paintings contain “both contemporary truths and secrets of the oldest living culture in the world,” though those truths did not seem to involve colonialism. While Aboriginal people exist (suspended in time, out in the desert), settlers apparently do not. But no matter: the paintings come cheap. Real contemporary art runs into the billions, but you can get a Bill Whiskey for some hundred thousand. Maybe an Emily Kame Kngwarreye for less than a mil’.

K.A.R.

Jobs for Girls with Artistic Flair |

BOOK

Debut novel by June Gervais; The Alchemist for LIRR riders.

J.M.

Turn Every Page |

DOCUMENTARY

It seemed like Robert Moses was everywhere in 2022 — not just in New York’s urban landscape, but also on stage at The Shed, in a Hopper exhibit at the Whitney, and most recently, in filmmaker Lizzie Gottlieb’s latest project. The movie is ostensibly about two other Roberts — biographer Caro and his longtime editor Gottlieb (also Lizzie’s father) — but those Bobs spend a huge amount of time discussing the first. We see in Moses’s rapacious power-brokering a parallel to the wordsmiths’ literary ambitions. His obsessive attention to detail was channeled into megalomaniacal construction projects; theirs into the placement of semicolons throughout the five books they’ve collaborated on. They may not have razed any neighborhoods as part of their process, but at the very least, they share Moses’s air of secrecy. When is the sixth tome coming out? The Bobs (both around 90) say we aren’t allowed to ask.

E.S.

Euphoria |

ART

Julian Rosefeldt’s giant film installation at the Park Avenue Armory billed itself as an “absurdist reflection on the history of human greed,” but it was more like an anarchic game of exquisite corpse. The show consisted of a series of short, stylized clips in which actors read unattributed quotes from such luminaries as Sophocles, Audre Lorde, Ayn Rand, Snoop Dogg, and Michel Houellebecq. Life-size projections of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus ringed the stage. In one segment, employees at a bank broke out into spontaneous acrobatics while counting money, making it disappear, and setting it aflame. In another, Cate Blanchett voiced a tiger that roamed an empty supermarket, reciting Marx, Adorno, and Terry Pratchett. Any heavy-handed consumer critique was undercut by Rosefeldt’s silliness: at the end, the creature licked some tomato sauce, laughed, and began to sing an aria.

R.F.

This Beautiful Future |

THEATER

In this production of Rita Kalnejais’s 2017 play, a seventeen-year-old girl quarrels with, fawns over, and eventually bangs a young Nazi. The set, a pink, womblike bunker in occupied France, was one of the few understated elements of its autumn run at Cherry Lane Theatre — which indulged in several daydream sequences, a pillow fight, and fever-pitched debates over Hitler’s impending surrender. Meanwhile, the couple’s older selves watch the action unfold from a glass karaoke booth upstage, occasionally jumping in to perform anachronistic pop ballads. Among them: Adele’s “Someone Like You,” which inexplicably turns into an audience sing-along. It’s unclear whether the play is a metaphorical plea for bipartisanship or an ill-advised attempt to humanize Nazis, but either way, it succeeds about as well as an auditorium of theater-goers trying to harmonize to early-aughts pop songs.

L.A.

Brian G. Hughes |

PRANKS

This turn-of-the-century businessman made his fortune as a cardboard-box manufacturer, but was better known as an “author of humorous hoaxes.” His practical jokes drew on the absurdity of the commodity fetish: burying “gold” — brass filings — at the beach and watching the boardwalk collapse in the resulting scrum; proudly donating a plot of land in Brooklyn for a public park, later revealed to be sixteen square feet; entering a “tramp cat” into a Madison Square Garden cat show under the name “Nicodemus, by Broomstick out of Dustpan, by Sweeper, by Brush,” valued at more than $1,000 but not for sale. Kept in a gilded cage and fed ice cream and chicken, Nicodemus won a prize. The frequency with which Hughes made headlines suggests that, then as now, the public enjoyed when those at the top admit they’re scammers. But unlike with our modern jokester-barons, Hughes’s hoaxes outshone his other enterprises. When apoplexy took him at 75, his obit read, “BRIAN G. HUGHES, FAMOUS JOKER, DIES.”

W.G.

Listening to Kenny G |

DOCUMENTARY

Penny Lane seeks to unpack the thorny career of the world’s most famous elevator musician, interviewing talking-head critics and musicologists who squirm as they attempt to parse the popularity of Kenny’s syrupy sax tones. But the film’s most perversely compelling aspect is the extensive time spent with the G-man himself at his palatial Seattle compound. Lane lets the affable, slightly dead-eyed megastar speak for himself — showing off his daily three-hour practice regimen, his collection of golf trophies, and his private plane, while using record-sales stats to ward off critics. Behind the all-American ambition, there’s an almost loveable guilelessness to the man. Note the awkward way he admits that white privilege might have contributed a smidgen to his success. Or the fact that he kicks off an early scene with this confession: “I don’t know if I love music that much.”

T.P.

Bigtop Burger |

YOUTUBE

Animator Ian Worthington’s very short web series, which debuted in June 2020, is one of the pandemic era’s few non-corny paeans to the beleaguered American worker. Its nine episodes follow a clown-themed burger truck, whose motto (“Hot Tires… Hot Burgers!”) is roughly as explicable as the staff’s job requirements — from wrestling “jacked” elk for meat to dueling roadside with their non-clown-themed rival, Zomburger. Coworkers Penny, Tim, and Billie nonchalantly accept the antics of their boss, an actual clown or possible extraterrestrial named Steve who yearns to be “back on Broadway, yet again” as Old Deuteronomy in Cats. “Everything is fine,” Steve often says. “Don’t phone the fire department.”

S.S.

The Eternal Daughter |

FILM

In The Souvenir (2019) and The Souvenir Part II (2021), Joanna Hogg cast Tilda Swinton’s real-life daughter as Hogg’s younger self and Swinton as her mom (with Alice McMillan playing a young Swinton, Hogg’s actress friend). When Hogg announced her intention to make a movie about her relationship with her mother, in which the Hogg character is roughly the age of the mother in the Souvenir movies, Swinton asked if, this time, she could play both parts. The result is pure horror — in the best way possible.

R.P.

Jeon Jungkook, Princess of Wales |

THEORY

During BTS’s musical hiatus, brought on by mandatory military service, the band’s aptly named stans (the “ARMY”) have developed an ironic but thoroughly researched and passionately defended theory that the group’s youngest member, Jeon Jungkook, is the reincarnation of Diana Spencer. The pop star was born a day after Di passed away in 1997. Like the late princess, Jungkook grew to 5’10” and is something of a daredevil, and his Diana-esque smile resembles that of a mischievous cartoon rabbit. Perhaps Jungkook fears microwaves because Diana once “nearly set the kitchen on fire” while cooking at Kensington Palace. Perhaps his drowsy appearance on a September 8 livestream was Di’s soul taking over so she could “finally witness the death of Queen Elizabeth.” Jury’s still out on whether Jungkook has read Spare.

A.K.

The Chinese surveillance balloon |

RECON

Since 1783, when spectators on the grounds of Versailles watched as a sheep, a duck, and a rooster ascended in a wicker basket, balloons have been instruments of Dadaist disruption, and this one, shot down last weekend off the coast of South Carolina, was no exception. Traveling at nearly twice the altitude of a commercial jet, the balloon carried winglike solar panels and a cabin packed with surveillance equipment. It was described in news reports as “the size of three school buses.” Tracked across the internet in real time, it also triggered a series of profound questions, though none about its echoes of Donald Barthelme’s 1966 New Yorker short story in which a gigantic balloon short-circuits ordinary life in the city, replacing it with the language of aesthetic contemplation, anxiety, and wonder. In the end, Barthelme’s balloon turns out to be a kind of love letter meant to capture the attention of the beloved, a “spontaneous autobiographical disclosure.” It does its job, then gets deflated and stored for hypothetical future use — “awaiting,” the final line reads, “some other time of unhappiness, some time, perhaps, when we are angry with one another.”