Mentions | Issue 16

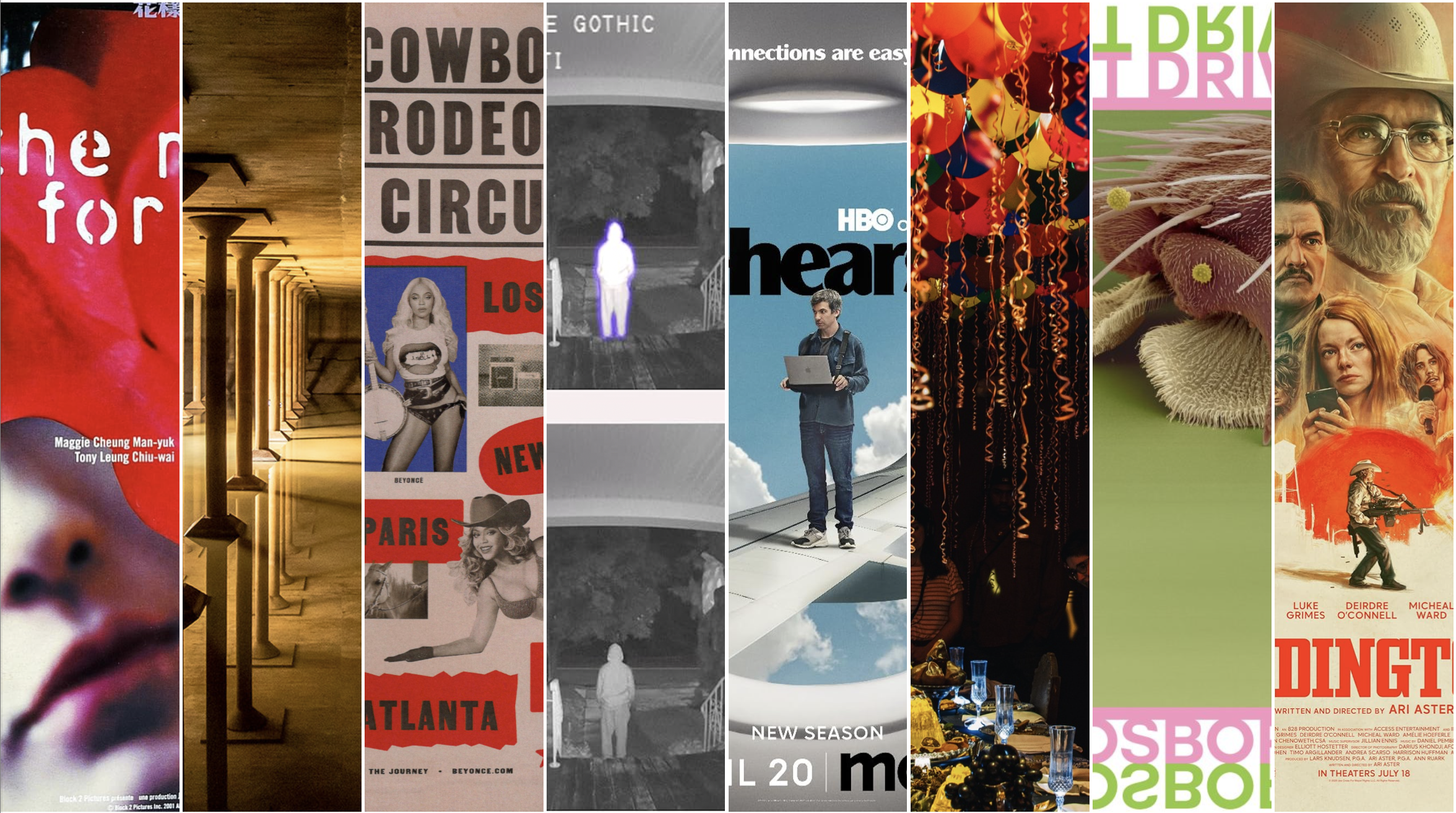

After the rose-toned feast that is Wong Kar-wai’s 2000 opus, his short of the same name released the following year — and recently revived at IFC — goes down like a digestif. Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung return as a miraculously magnetized pair of strangers, but this time they meet in an ice-blue Y2K convenience store instead of in a shabby-chic 1962 apartment building. The film is less a sequel than an alternate universe, one that is frothy and absurd; the star-crossed lovers bond over concurrent nosebleeds and spend much of the nine-minute runtime in a cake-smeared makeout, the frame dominated by her hands in his conspicuously un-gelled hair. At last, Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan get to fool around, uncoiffed.

I.A.

According to director Joe Wright, every camera used to shoot this eight-part series bore a sticker that read “this machine kills fascists,” a nod to the famous inscription on Woody Guthrie’s guitar. But the finished product lacks the moral clarity of, say, Guthrie’s “Tear the Fascists Down.” Rather than mocking or belittling fascists, Wright chose instead to explore the libidinal allure of squadrismo through sequences of gratuitous blackshirt violence set not to folk but to EDM. If there’s a critique buried somewhere in here, it’s been lost amid the social media flood of what can only be described as Sigma Mussolini fan edits.

T.B.

Two novels with this title came out in the U.S. this year. Katie Kitamura’s is about an actor playing multiple roles in her family. Pip Adam’s is about an audient spaceship fueled by the speech of its imprisoned giants. Four other Auditions precede them: Stasia Ward Kehoe’s young-adult novel in verse, Barbara Walters’s autobiography, Ryū Murakami’s horror novel, and Michael Shurtleff’s how-to guide for actors. Each is good — Kitamura’s is the best — but only Adam’s has a great title.

B.G.

Take a moment to consider the beguiling, poignant symmetry in the series of events that have befallen members of the Dourif family. In The Exorcist III (1990), the brilliant, reliably batshit Brad Dourif plays the Gemini Killer, a possibly possessed and highly charismatic lunatic, straitjacketed and stashed away in an empty wing of a Washington, D.C. hospital. (He had to put up with the same business in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, but the Gemini could eat Billy Bibbit for lunch.) Now, on HBO’s The Pitt, Brad’s daughter Fiona plays Cassie McKay, one of the attractive, harried E.R. doctors, who cannot leave her workplace without being arrested thanks to a court-mandated ankle monitor. Both are charming and clever; both flail bitterly against the sinister forces confining them (for Brad, it’s the demon Pazuzu; for Fiona, it’s the Pittsburgh probation court). None of the nurses at Pittsburgh Trauma have been decapitated, as they were in The Exorcist III’s Georgetown University Hospital. But there’s always next season.

P.S.

In FENCE editor Harris Lahti’s debut novel, houses aren’t the only things that are torn apart and rebuilt. With tight, lyrical prose, Lahti follows a father and son duo, Vic and Junior Greener, as they flip foreclosed homes around the Hudson Valley. The two meet an assortment of mysterious characters, like the seven-foot tall garbageman who leaves a grease stain when his head hits the Greeners’ ceiling, or the wealthy, incestuous couple who may or may not keep their mother chained up, or the twins with shotguns who confront Vic to try to get their uncle’s smut collection back from the Greeners’ latest flip, only for Vic to pay them to help rip up the carpet. There isn’t much closure in Foreclosure Gothic, only a reminder that, while none of us ever go home again, we never really leave it either.

R.W.

Nathan Fielder’s HBO show made at least one thing clear: between the rotating cast of babies raised as a single baby in season one, and Fielder’s turn as a diapered man-baby being raised as a baby-baby in season two, the man is fascinated with babies.

A.G.

Europe’s “Mecca of photography” tried to position itself as radical this year. The theme of the 56th installment of the annual festival was “Disobedient Images,” in celebration of the role of the photograph as “an instrument of resistance.” Yet none of the dozens of exhibitions on view included any mention or image of the genocide in Gaza. (When artist Nan Goldin projected the word “GAZA” behind her on stage as she accepted the Women in Motion award, several attendees walked out.) An even clearer expression of defiance came from the unaffiliated documentary studio Doubledummy, which staged a counter-festival drawing attention to work by Gazan photographers to critique the festival’s omission. It turns out photos can only become instruments of resistance when they’re given the space to be seen.

A.D.

After a showing of his attempted magnum opus Megalopolis this past summer at the Chicago Theater, the director wheeled out a whiteboard that listed ten concepts he believes we must abolish in order to promote human flourishing. The first three were time, money, and work. Perhaps Coppola’s rebellion against the latter explains the many factual errors in his lecture, including his misdating of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which he claimed are ten thousand years old and predate the Epic of Gilgamesh. But the crowd didn’t challenge him. The first audience question was whether Marlon Brando really ate cheeseburgers in a canoe.

B.S.

Duke Ellington turned toward God near the end of his long, mostly secular career. The King of Big Band Jazz released two religious albums in the sixties, the second more emphatic and riveting than any in his career. This aptly named 1968 record is like a faith-led IMAX event — all horns and crashing cymbals, with plaintive strings replacing his usually lithesome piano. On one track, the Swedish vocalist Alice Babs, whose range spanned three octaves, sings an operatic scat arrangement that contains no actual words. Duke called it “TGTT,” or “Too Good to Title.”

W.D.

An early work of autofiction so effective that it renders its successors all but unnecessary, French artist Édouard Levé’s slim 2005 volume consists of nothing but statements about the author: “I sing badly, so I don’t sing. Because I am funny people think I’m happy. I want never to find an ear in a meadow.” The sentences, set down almost, though not entirely, at random, are detached and flat, but produce an almost miraculously coherent effect. As protagonist, Levé both surprises and grows into a familiar type: the artist struggling with despair. Levé took his own life in 2007, ten days after turning in his following book, Suicide, which elaborated on a story in Autoportrait. But here, you can see him puzzling through possible reasons to live. “Some day I will wear black cowboy boots with a purple velvet suit.”

A.L.

The grandson of opium smuggler John Perkins Cushing, little-known outside of Rhode Island’s toniest quarters, may be best remembered for his association with the artist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who founded a museum of some repute in New York. Cushing’s retrospective at the Newport Art Museum’s “Cushing Gallery” confirms that his own work was largely unremarkable, save for some delightfully outré Orientalist-inspired paintings. (One study for a mural cast Cushing’s redheaded wife Ethel in a kind of harem scene, flanked by turbaned attendants.) The exhibit was organized by a guest curator, following layoffs in 2024 of the museum’s entire curatorial staff for reasons that remain murky, and co-sponsored by Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman — perhaps in an attempt to ingratiate himself with locals in the wake of controversial (and probably sinkhole-causing) construction on his new mansion.

Z.N.

It’s difficult for novels about neurotic losers crushed by indifferent bureaucracies to avoid the long shadow of Kafka. But in her debut, English writer Nell Osborne manages to achieve a grimly comic sensibility that feels distinctly her own. The narrator of this tale of misery and doom has a gift for Customer Service Voice and a strong grasp of the passive-aggressive potential of an overly cheery exclamation point.

S.R.

“America Has a Problem” is on the set list of Beyoncé’s tenth concert series, but after the visual onslaught of stars and stripes one would be forgiven for assuming the production designer forgot. The nearly-three-hour spectacular was rife with Americana, from classic Cadillacs to cardboard cutouts of bald eagles, and featured a video interlude that included a dizzying Attack of the 50 Foot Woman homage in which a gargantuan Bey traipses across past world landmarks, stopping to light her cigar on Lady Liberty’s torch, and get winked at by the Lincoln Memorial. Do the troops feel respected by the product managers in assless chaps removing their bejeweled cowboy hats for Queen B’s rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner?” I didn’t ask, and they certainly wouldn’t tell.

G.A.

Just south of Salt Lake City, you can ride a six-dollar company shuttle to the edge of the Bingham Canyon Mine, the largest open-pit excavation site in the world. (Signs along the way warn workers to “control the hazards.”) Like “Spiral Jetty,” the region’s more famous earthwork, the copper mine will leave you thinking about scale; from three Empire State Buildings up, ore-toting trucks appear planktonic. But even more mind-bending than the view is the experience of reading about Rio Tinto’s “environmental stewardship” on their website right after staring into an abyss that was once a mountain.

C.L.

This trendy exercise program, created in 2019 by podcaster and supplement entrepreneur Andy Frisella, went viral on TikTok during the pandemic and has remained popular in hustle culture circles. Frisella boasts of “winning the war with yourself” through “transformative mental toughness” over the course of 75 days. Adherents are given, among other tasks, a daily reading goal: ten pages of any self-help book. This endearingly petite morsel of homework is supposed to be roughly as difficult as the other assignments, such as drinking a gallon of water or completing two 45-minute workouts (one outside, regardless of weather). According to the program’s introductory email, “audiobooks DO NOT COUNT.”

O.N.

The target audience for The Shed’s latest immersive offering appears to be bats: visitors are instructed to surrender their phones, remove their footwear, and “follow the light,” only to be repeatedly plunged into pitch blackness, groping along corridors like penitents in a haunted house stripped of actors and fun. Based on a wisp of a gothic tale about a princess obsessed with a moonlit maze, the nearly hour-long guided crawl across grassy carpets, sand, and gravely symbolic set pieces feels at once too long and too short. (Daisy Johnson wrote the somnolent script, which is conveyed to us, in Helena Bonham Carter’s feathery ASMR voice, through bulky headsets.) Any feeling of suspense is mostly of the will-I-get-a-fungal-foot-infection variety.

R.F.

An almost palpably self-satisfied Ari Aster frames his latest overstuffed foray as a Western from the very first shot: a lone man shuffling past tumbleweeds into a town at the edge of civilization. But this Covid period piece is also garishly festooned with “2020” motifs, from surgical masks, iPhones, and water-leaching data centers to hypocritical Black Lives Matter protesters and a socially distanced fundraiser where Pedro Pascal slaps Joaquin Phoenix (twice). Then Antifa flies in on a private plane. The film made me long for the comparatively subtler Beau Is Afraid and its giant penis monster.

J.S.-G.

Hannah Neeleman, the Mormon tradwife behind the infamous Ballerina Farm, joined Substack in the spring to “share things close to my heart,” including lasagna and focaccia recipes, a tribute to her deceased father, and an announcement about her new Utah farm stand. The real action, though, takes place in the subscriber chat, where fans ask how to store flour and discuss whether pregnant women should eat raw milk ice cream (no response from Neeleman, but Ballerina Farm’s soft serve is pasteurized). Recently, posts soliciting donations for Gaza converged with Neeleman copycats boosting their own channels. Commenters seemed divided on whether the chat should stick to “home life topics,” raising the question: what would Jesus report as spam?

D.H.

David Cronenberg is the only working director who understands what the fuck is going on with technology right now. The Shrouds is post-late style, so stilted that it seems a cross between a filmed theater production and a dream. Silver fox Vincent Cassel, a clear Cronenberg stand-in, delivers his lines with an eerie intensity A.I. could never replicate. The Promethean hope of conquering death — an ambient obsession across Silicon Valley — is revealed to be a mere conduit for the expression of psychosexual hang-ups. The scariest moment of the film comes with the reveal that Cassel’s character drives a Tesla. Beneath the intellectual carapace, Cronenberg has the heart of a comedian.

M.F.

The narrator of César Aira’s 2018 novella has left behind a lucrative career as a writer of genre fiction to become a full-time consumer of opium. “The human is no more than a format, the content is left up to chance,” he thinks. The same goes for the novella, which recounts dreamlike stories of getting high, having sex, and being the one person uniquely situated to save a world teetering on the edge of oblivion. The world of the book, for all its secretive sages, potent substances, and labyrinthine architecture, is knowable, at least to César Aira. It is Buenos Aires. The novella is, so far, less so for Anglophone readers: it has not yet been translated into English.

B.H.

This municipal auction platform with a bare-bones, Craigslist-style interface offers a welcome, albeit strange, respite from the excesses and pop-up ads that plague most online shopping experiences. The site describes itself as a “liquidity services marketplace,” providing a centralized portal for offloading government surplus, though it is impossible to know the true provenance of whatever item you’re buying, save for the seller and their location. (Whose 1.2-carat marquise diamond ring is this, and are they still looking for it?) Items up for grabs as of this writing include a pallet of years-old MREs (Meals Ready-to-Eat); a half-dozen CPR dummies, clustered together as though languishing in a Boschian hell; and a little white church in rural Illinois with a positively post-apocalyptic interior (starting bid: $19,900).

C.Ch.

António Lobo Antunes offers Greater Lisbon’s answer to The Sound and the Fury’s Compson family, complete with its own self-drowned firstborn, near-mute youngest child, and middle son of the usual type (estranged, violent, involuntarily celibate). The Caddy stand-in, and only daughter, narrates a final visit to her childhood summer home. Deftly rendered in English by translator Elizabeth Lowe, the novel is a nonlinear, minimally punctuated onslaught of memories, interspersed with refrains of unattributed dialogue that give voice to furniture, plush toys, and blackbirds. When the protagonist bids farewell to a grove of pine trees beside the house, their parting message may well echo the sentiment of most readers at the book’s end: “How mean of you to leave us.”

J.E.

This 87,500-square-foot decommissioned reservoir, built in 1926, lies underneath Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Park, which offers walking trails alongside a mud-colored river and towering overpass supports. Forgotten for years, it reopened in 2016 as a tourist site and performance space called the “Cistern,” a name intended to evoke the monumental Byzantine ruins beneath Istanbul. But the Houston version involves more concrete and more tales of municipal corruption. You can take a guided tour to learn about the city’s history of dubious water sanitation infrastructure, including a memorable anecdote about a three-foot-long eel carcass clogging a downtown pipe. To demonstrate the facility’s seventeen-second echo, the guide encouraged us to scream into the musty darkness. “Leave it all inside the Cistern!” she yelled, as tourists from Dallas howled beside me.

A.K.

Rarely does the doorstopper moonlight as page-turner, but Benjamin Moser’s dazzling 800-page biography deserves a spot in your beach bag. Come for the riveting account of the highest-brow New York intellectual’s life and times, stay for the epic record of her sexual conquests: Annie Leibovitz, Warren Beatty, Rothschild heiress Nicole Stéphane, Joseph Brodsky, Lucinda Childs, Bobby Kennedy. (Sontag loved lists.)

K.V.

This two-tower development rising over New York City’s West Side Highway contains an eighty-million-dollar penthouse, a one-million-dollar wine cellar, and an 82-foot swimming pool. But it may be more interesting to consider what the building doesn’t have, like nearly five hundred affordable housing units or an outdoor public recreation center — two features that were promised, on a now-scrubbed government website, when the city rezoned the land in 2016 in order to allow Atlas Capital Group and Westbrook Partners to, as they say in the real estate business, go nuts. Atlas and Westbrook shook hands and then promptly sold part of the land to another developer that built a swanky new office building for Google, leaving room for just a third of the proposed units. Those past pledges seem to have been lost in the fog of 80 Clarkson’s private steam room.

J.I.

My favorite detail in Sam Tanenhaus’s biography of William F. Buckley Jr. is that when the intellectual father of the neoconservative movement got peckish on sailing trips, he liked to raid lobstermen’s traps for a nosh. Though only a minor skirmish in the class war Buckley waged from above, the anecdote calls to mind a preening interview he gave The Atlantic in 1968, four years after Yale had awarded Martin Luther King Jr. an honorary law degree. Dr. King, Buckley sneered, “more clearly qualifies as a doctor of lawbreaking.” Tanenhaus knew and liked Buckley, but the portrait that emerges in this careful book, sketched over the course of three decades of research, makes it hard to share the author’s affection for his subject. Buckley was a covert correspondent of J. Edgar Hoover’s, the secret funder of a newspaper in South Carolina founded to oppose desegregation, a reflexive hawk, a free-market evangelist, and an anti-communist (he was once pleasingly referred to as “McCarthy’s egghead”). In one respect, at least, Buckley has surpassed his old rival Gore Vidal: Buckley’s authorized biography breaks a thousand pages.

C.Co.

In 2006, the Campari Group announced that it would stop using cochineal insects to give the company’s namesake liqueur its trademark reddish hue, citing “uncertainty of supply.” In the U.S., Campari switched to a vegan dye, which may or may not include Red 40 — an additive HHS Secretary RFK Jr. hates almost as much as vaccines. It remains to be seen whether Campari will follow other multinational food and beverage corporations, which have informally agreed to phase out artificial dyes. But the time is ripe for a campaign to reindustrialize American insects, and, as the pro-bug barback meme account @moverandshakerco put it, “make Campari bugs again.”

L.M.

Mentions | Issue 15

The largest-ever U.S. exhibition of work by Ai Weiwei quotes the artist’s famous line — “Everything is art. Everything is politics.” — but stops short of making a clear statement on protest or freedom of expression. The most instructive moment, at least during my visit, was supplied instead by one of the “touch stations” devised by the Seattle Art Museum, where grabby visitors can interact with samples of Ai’s materials. I watched as a young girl ran her hands over a slab of marble, then turned to do the same to the real artwork beside it. Her mother intervened and tried to explain the difference between the two, with little success.

E.L.

The 7,066 reviews of this contentious body of muddy water once offered a glimpse into the minds of visitors unconcerned with its name. The “most relevant” posts were filled with childhood snorkeling memories and vaguely spiritual musings; one satisfied customer wrote, “the Gulf has made us a part of her, and she is a part of us.” By contrast, a single-star review called the Gulf “a constant disappointment… a thirty-year-old son who won’t leave home.” Earlier this spring, Google archived all but one of these comments, leaving the note: “Posting is currently turned off for this type of place.”

P.A.

It’s never a bad idea to listen to the more-than-35-hour audiobook of Anna Karenina, but the version put out by LibriVox, a platform where volunteer readers narrate works in the public domain, is especially fun. Chapters are read by different people, and the vastly different levels of competence on display lend a touching, amateurish quality to one of the greatest books ever written. Come for the novel’s deft psychological portraits, stay for the global accents, the shameless name-dropping of several readers’ personal websites, and the staggering variety of ways to pronounce “Karenina.”

S.C.C.

The newly reopened Yale Center for British Art has received rave reviews, but I have yet to see any mention of the museum’s best feature: its bathroom. Forget Cecily Brown and J.M.W. Turner; say hello to Louis Kahn’s colossal concrete pillar, tracing a curve to the sink. The mirrors come with dressing room lights fit for a starlet (Madonna did, after all, visit the YCBA in April). The palette isn’t anything out of the ordinary — whites, grays, and the metallic reflections of the paper towel dispenser and trash can. Yet this blankness suits the room’s function as both a respite from the noxious gaze of self-proclaimed art critics and a backdrop for an Instagrammable mirror selfie to broadcast the fact that you are, after all, one of the dilettantes you despise.

N.K.

Andrea Arnold’s latest injects her usual working-class narratives with a dose of the surreal. Twelve-year-old Bailey, who squats with her dad and half brother on a council estate in Kent, meets Bird, a drifter who may or may not sometimes transform into a crow. A story that could be mawkishly sentimental succeeds by tempering its fairy-tale elements with enough brutal, haunting, and hilarious moments (suitably scored by electronic musician Burial). By the film’s end, its titular character’s shape-shifting barely seems remarkable. How strange is a bird-man after you’ve watched Bailey’s dad (Barry Keoghan) try to pay for his wedding by singing Coldplay to a psychedelic toad?

D.F.

A faithful adaptation of Herman Melville’s whale epic in 2025 would probably lead to a speech by JD Vance blaming wokeness for making Moby-Dick gay. Unfortunately, we won’t get the pleasure of correcting Vance on this one, since the Met’s operatic rendition abandoned the novel’s queer themes, among others, in favor of Ahab’s monomania. In the first scene, instead of seeing Queequeg and Ishmael share a bed in “the most loving and affectionate matter,” we get Queequeg awakening Ishmael with loud pagan rituals from across the hull. The opera seems to disagree with the novel’s claim that there’s “better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian.”

J.B.

Harmony Korine’s 2009 black comedy about constipated Nashville dumpster divers, now on the Criterion Channel, follows a group of social outcasts wearing rubber old-people masks, literally humping trash — and any other object, inanimate or otherwise, they can find. Repulsive, crude, unapologetically aimless, and literally unforgettable, it exemplifies the once-revelatory aesthetic of the leading cinematic anthropologist of American muck. Sadly, in recent years, Korine has been producing a different kind of trash: something he calls “blinx,” a kind of techno-futurist post-cinema involving edgy infrared photography, giant baby faces superimposed on home invaders, and Travis Scott.

T.T.

Bryan Johnson is widely known as a kind of aspiring vampire: a tech millionaire who regularly injects himself with blood plasma (including, on at least one occasion, that of his teenage son Talmage) to reverse his own aging. But in this Netflix documentary-slash-P.R.-vehicle, Johnson comes off less like a ghoul than a sad little boy whose messianic ambitions clearly spring from chronic loneliness. He does seem happy to spend all day go-karting with Talmage, who, much to his father’s distress, is about to leave for college. “Do you think he’ll be okay on his own?” an interviewer asks not the father, but the son. “I do worry about him,” says Talmage. Johnson inspires a similar kind of parental concern in the viewer. His body, the subject of so much of his attention, is sculpted but pale, impossibly lean, and oddly smooth. You’ll want to feed him.

A.L.

Thrilling stuff for history-buff dads who game: players in this addictive web simulation are politicians in the Weimar Republic trying, and usually failing, to fend off the Nazis. We begin in 1928, with Germany’s vibrant democracy in full swing. As it unravels, we’re presented with several options: patch things up with the revolutionary communists? Pander to the bourgeoisie? Unfortunately, it seems the key to foiling fascism is preventing the doddering octogenarian president (in this case the mustachioed Paul von Hindenburg) from running for another term. Ah.

B.S.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of Alive!, the career-making live album by glam metal giants KISS. But it’s likewise an opportunity to celebrate an alternative archive of the band’s theatrical stage presence: this bootleg compilation of frontman Paul Stanley’s delirious stage banter. With dubious sourcing but quality audio, presumably compiled far outside the purview of the band’s notoriously maximalist approach to copyright enforcement, it provides over sixty minutes of ’70s time travel experienced through groan-inducing double entendres, repetitive song intros, and goofy local call-outs. The guitarist otherwise known as “the Starchild” delivers it all in a glorious, demented Noo Yawk drag queen register, punctuated by strangely multisyllabic “Woos!” and “Alrights!” that defy both transcription and good taste. Stanley, a supposed Knight in Satan’s Service, turns out to be something more like a cock-rock politician, delivering a stump speech by turns mundane and electric.

A.G.

Finally, a reprieve from the self-consciously surreal workplace novel. Instead of nudging alienated workers around outer space (Olga Ravn’s The Employees), a supernatural factory (Hiroko Oyamada’s The Factory), or a pirate ship (Hilary Leichter’s Temporary), Claire Baglin’s masterful debut, translated from the French by Jordan Stump, takes place in the terrestrial Normandy auto manufacturing districts of Baglin’s youth. One storyline, in which a child named Claire sees her father crushed by ill-paid factory work, nods to the nineteenth-century “social problem” novels of authors like Elizabeth Gaskell, who posited that industrialization prevented men from serving as good patriarchs. But a parallel narrative about teenage Claire’s fast food job pivots from the family to the individual, offering a Steinbeckian catalog of the occupational abuses endemic to unregulated temp work. Eschewing dystopia to revisit the moves of classic labor literature, Baglin asks — like the proverbial mom responding to her McDonald’s-craving child — why we make up bad jobs when we have plenty of workers’ rights violations at home.

I.C.

If the concept of a Canadian “national culture” conjures the same kind of despair as the terms “brand loyalty” or “singles cruise,” Canadian filmmaker Matthew Rankin should be applauded for jettisoning the idea entirely from the Winnipeg of his latest film. The main character, played by Rankin and sharing his name, comes home to a version of the prairie city transformed, by magical fiat, into a neighborly Persian community. In this Winnipeg, Farsi has replaced English and Tim Hortons employees serve tea from samovars. A shotgun marriage between the poetic-realist tradition in Iranian cinema and the city’s brutalist architecture proves to be surprisingly harmonious, a genuine multicultural love match. The English title evokes the film’s utopian sensibility, but it’s the unexpectedly unmetaphorical Farsi title that catches the movie’s humor: آواز بوقلمون translates to The Song of the Turkey.

J.C.

Three of the canvases included in this career-spanning survey at Gagosian date back to the totemic abstract expressionist’s final productive decade, characterized by a stylistic break so forceful it suggests a crisis of identity. Gone is the dripping wreckage of the triumphant ’50s and ’60s. Instead, the ’80s works inhabit a vibrating cosmos of white void, black line, and warm color curvature that could plausibly be called serene. Explanations for this volte-face hover around the artist’s decision to quit drinking and, more ominously, his worsening Alzheimer’s. The latter led to an increased role for studio assistants in producing his canvases, and, towards the end of his life, a tight-lipped legal conservatorship over the artist and his estate. The taboo around these circumstances, and their glaring implications for these final paintings’ provenance, clearly serves the bottom line. At $300 million, de Kooning’s “Interchange” (1955) is the second-most expensive painting of all time. Even an untitled ’80s work of this later style fetched $385,000 in 1987 — none too shabby for an auction held a few weeks after Black Monday. But the exhibit’s suggestion of an “endless” continuum between these periods serves neither Kooning’s strange and majestic late canvases nor our understanding of the art-historical turn towards an aesthetics of asset management that haunts them.

R.M.

In Tom Noonan’s morose 1994 comedy, Jackie, an executive assistant at a law firm, invites her colleague Michael, a paralegal, over for dinner. Subverting the rom-com fantasy in which initial awkwardness gives way to love, Noonan’s characters remain completely unfathomable to each other — never more so, perhaps, than when Jackie prepares the main course: a sludge-like scallop dish, which she heats in the microwave before piling on Michael’s plate.

A.V.

Many beloved alt-weeklies have suffered from declining ad revenue and fallen into the hands of dimwitted financiers — think The Village Voice, the San Francisco Bay Guardian, the Boston Phoenix. Others, like St. Louis’s Riverfront Times, live on as horned-up OnlyFans zombies. The RFT once published exposés on topics like police corruption and the death of FBI-surveilled Ferguson protester Darren Seals. Now, the paper primarily runs A.I.-written sponcon with titles like “Lily Phillips Says She Used To Enjoy Extreme Sex Events For Fun Before OnlyFans” (since deleted) and “Man Starts Leaking Cholesterol Through His Pores: High Fat Diet Goes Very Wrong.” It’s a good thing no real news is happening.

D.T.O.

This typeface, which replaced Calibri as the default font for Microsoft 365 in late 2023, is supposed to be friendlier, more trustworthy, and better suited to high-resolution screens. But to my semiprofessional eye, it looks like a squashed version of its predecessor, as if someone dropped an anvil on all those humanist letterforms. (The characters are certainly wider; Aptos fits roughly thirty fewer words on a page.) The font’s recent success coincides with a change in its name. Rechristened for a town in Northern California that apparently “epitomizes the font’s versatility,” Aptos follows in the footsteps of fellow name-changers Norma Jeane Mortenson, Ralph Lifshitz, and even the British royal family, who became the Windsors only after ditching “Saxe-Coburg and Gotha” for being too German. “Too German” might also have been a problem for this typeface, formerly known as “Bierstadt.”

Z.G.

The third generation of this not-quite-dumb phone is purportedly smart enough to give directions, but not smart enough to send an email. Some skeptics have questioned the smartphone price ($799, or $599 for preorders), while others find the introduction of a camera and the promise of an optional digital wallet function to be a Bay Area bridge too far. The company, Light, has pointed out that its commitment to privacy means it doesn’t use cash from data collectors to defray costs; apparently, the uncompensated sale of personal information translates to consumer discounts. Or maybe the anti-tech tech guys are fleecing us. In any case, I’m willing to part with my Motorola RAZR V3 Pink (super rare) for $149 or best offer.

K.P.

Presenter-read advertisements, the last vestige of amateur podcasting, offer a glimpse into a show’s imagined audience. What can the selection of products hawked by former Obama aides teach us about the average liberal American male? That he wants to restore his gut lining by swilling cow colostrum in sungold apricot flavor, burn fat while lounging on his direct-to-consumer mattress in bamboo delicates, avoid hangovers that could impede productivity, eat chicory root inulin and tapioca starch cereal for dinner, and consume vegetables in powder form.

J.A.

This new mob feature answers a question only a movie producer would think to ask: what would happen if you tried to make The Irishman without Martin Scorsese? Goodfellas producer Irwin Winkler hired some of the hottest talents of the early 1990s — director Barry Levinson (Rain Man), screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi (also Goodfellas), cinematographer Dante Spinotti (Heat) — and cast Robert De Niro (also Goodfellas, also Heat) to play both Frank Costello and Vito Genovese, the film’s central gangsters. In 1974, when Winkler first bought the rights, this project might’ve been on the cutting edge. In 2025, it’s a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy. The film is an hour shorter than The Irishman, but manages to feel an hour longer. Sometimes the greatest testament to an artist’s skill is how badly things go when they’re not around.

B.B.

Like Fleet Week for buckle bunnies, the Professional Bull Riders’ three-day event, sponsored by Monster Energy and the U.S. Border Patrol, brought 45 of the world’s best bull riders and their fans to Manhattan. The sold-out 2025 “Buck Off” at Madison Square Garden drew a distinctive crowd: out-of-towners in Farming Simulator merch alongside downtown types looking for a place to wear a cowboy hat with a little less irony than usual. The audience watched as human and bovine athletes (as the bulls are called) endured 135 dizzying rides — few lasting the qualifying eight seconds — before Lucas Divino, a seasoned rider from Nova Crixas, Brazil, claimed the nearly $46,000 purse. While the uninitiated may find professional bull-riding less overtly sexy than pop culture’s mechanical bull fantasy led them to imagine, there is something titillating about watching these small, durable men go bareback. Imagine the rider — often, a barely 150-pound twentysomething — as a jerky appendage, joined to the bull thanks only to the strength of his inner thighs and five firm fingers. Yeehaw.

S.A.A.

The work of Austrian theatermaker Florentina Holzinger, master of the crowd-pleasing abject and the so-called “Tarantino of Dance,” has previously featured cobalt blue vomit (Kein Applaus für Scheisse or “No Applause for Shit”), a spectator-splashing orgasm (A Divine Comedy), and a key extracted from a vagina (Ophelia’s Got Talent). Holzinger’s latest offers a churchly ritual wherein a chunk of one performer’s flesh is griddled and fed to another — a scene that, in Stuttgart, caused eighteen audience members to seek medical treatment for “severe nausea.” Undaunted, Berlin’s prestigious Theatertreffen festival named the play one of German-speaking theater’s ten “most remarkable productions” of the year. The U.S. might not be graced by Sancta anytime soon, but in February, Tanz — a grisly piece of dance theater that critiques ballet’s sexual fixation on women’s bodies by literally skewering dancers with meat hooks and dangling them from above — sold out its New York City run. Before Holzinger’s unholy power to transubstantiate metaphor into the scandalously corporeal, all heathens turn into believers.

S.I.B.

Alex Edelman’s one-man show about anti-Semitism opens with a decent bit about Koko the gorilla. But after getting that “benign silliness” over with, Edelman dives into the meat of his set: a Nanette-ian retelling of the time he crashed a neo-Nazi meeting in 2017. Though Edelman’s show hit Broadway in 2023 and HBO in 2024, it’s immediately obvious that the material was written years ago. Israel is rarely referenced, though Edelman does mention that his brother competed on the Israeli Olympic bobsled team. In subsequent interviews, the comedian has described his views on Israel as “heterodox.” Last year, when “the Israel-Palestine stuff” came up on Marc Maron’s podcast, Edelman said: “I’m obsessed with listening to it and thinking about it, but I’m not really sure where I stand yet.”

M.S.

Errol Morris managed to make a 93-minute film on the first Trump administration’s child separation policy without interviewing a single person directly affected by it. Instead, he focuses on the internal politics of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, lionizing the impotent civil servants who quietly expressed reservations behind closed doors. The only immigrants we do see — a mother and son crossing the border — are actors, their presence limited to a series of near-silent reenactments. Evidently, Morris saw white bureaucratic minutiae as the heart of the story. I guess I should have turned it off the moment I saw the words “MSNBC Films.”

M.K.

In McSweeney’s Quarterly editor Rita Bullwinkel’s story of eight women boxers, a finalist for both the Pulitzer and Booker Prizes this year, the human body is described with the precision of a butcher: we hear about a “toned cut of meat” and a “thin smashed cutlet.” Bullwinkel is herself a former competitive water polo player, and her characters’ honed forms prove exacting both in their ability to land punches and to move the plot forward at a rapid clip. Meditations on God, motherhood, family, death, and ambition are nestled among hopes dashed and dreams realized in this lean, excellent novel — no Rocky, all Bullwinkel.

P.B.

In acclaimed Timbuktu director Abderrahmane Sissako’s latest feature, Aya leaves her unfaithful fiancé at the altar in West Africa for a new, emancipated life in Guangzhou. Here, the “Chocolate City,” so called for its large African émigré population, is scrubbed of complexity: no one speaks Cantonese, but foreigners all know HSK 4 Mandarin; cops are cool; Chinese antiblackness never infringes on the personal lives of the film’s invariably friendly, reasonable characters. Aya’s love interest, who owns the boutique tea shop where she works, dotingly calls her “Black Tea,” a nickname no Chinese person would ever come up with because even Google Translate knows that black tea in Mandarin is “hong cha” (“red tea”). It is not races that fall in love but real people, and unfortunately, Black Tea has none of those.

A.Z.

Spoiler alert: dense, data-packed tomes on global inequality are not especially funny. But journalist Claire Alet and illustrator Benjamin Adam try valiantly to make Thomas Piketty’s 2020 follow-up to the door-stopping Capital digestible and entertaining. Through a family saga spanning eight generations and a coda that takes the form of six proposals for modern-day participatory socialism, the book brings us on a journey from feudal lords to modern tax loopholes, replete with historical line charts lovingly rendered in panel form and factoids about quantitative easing delivered via speech bubble. The illustrations are striking, and Alet does a noble job of condensing Piketty’s academic Everest into something more like a hill. But there are only so many laughs to be had while a cartoon aristocrat in a top hat tells you that you’re poor.

V.N.D.

The global clothing behemoth Uniqlo recently opened the first North American location of its eponymous coffee shop, housed on the second floor of the company’s flagship Midtown store. The minimal seating and airport-like ambience may disappoint Manhattanites looking for a welcoming “third space”; this site was once a Starbucks, and little seems to have changed. But the coffee was fantastic, despite the barista’s reaction to my Americano order. (“That’s the one that’s espresso, right?”)

M.S.

The cloistered Carthusian monks of the Grande Chartreuse monastery are best known for their eponymous liqueur, but spend far more time sitting in contemplative silence than collecting herbal ingredients for your next cocktail. In 2005, the filmmaker Philip Gröning distilled six months of footage from the charterhouse into an intimate record of this “communion of solitaires,” scored only by the sounds of monastic life: deliberate steps thumping on wooden floors, electric clippers buzzing at the in-house barber. The result — appropriately austere and quite seductive — lulls the viewer into a peaceful certainty much like the monks’ own. And if you’d rather not wait sixteen years (as Gröning did) for permission to visit, fret not: a former charterhouse at nearby Sélignac offers a silent retreat in the mode of the “Carthusian lifestyle.” Those monks have made at least one concession to modernity: sign-ups are accepted via Google Form.

C.P.

Even if you’re not all that interested in what America’s Marquis de Sade has to say about art, books, and weird things on the internet, you’ll find useful advice and minor revelations on his self-titled blog, where he responds to practically every comment. Some of his observations run to the banal — that coke is expensive now, and sincerity is good — yet he still manages to surprise. In one response, he encourages the user Diesel Clementine to “adopt a persona and make a bunch of friends who like the persona and want to be friends with that person, and then, after your persona has been friends with them for a while, revert to who you really are and confuse them.” Couldn’t we all stand to live our lives a little more like one of Cooper’s depraved protagonists? I, at least, plan to start signing off messages the way he often does: “xoxo, me.”