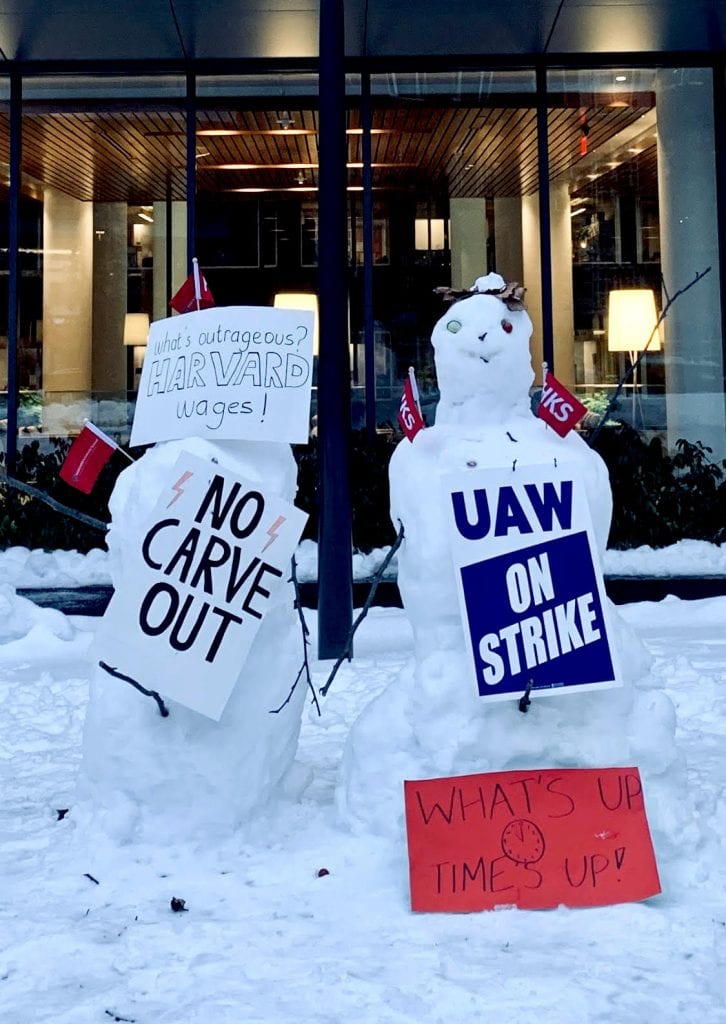

The picket line, courtesy of HGSU-UAW

The picket line, courtesy of HGSU-UAW

A Zoom handshake made it official: last Monday, Harvard University and its student workers’ union agreed on a year-long contract after two years of negotiations and one strike. This week, our 4,500 rank-and-file members—doctoral, masters, and J.D. students, as well as several hundred undergraduate course assistants—will vote to ratify the contract.

As a member of the union bargaining committee, I watched as Harvard slow-rolled the negotiation process over the course of more than fifty meetings. The university employed tactics straight out of the anti-union playbook used everywhere from Everlane to Amazon. The negotiators dismissed workers’ testimony (“Good story, if true”), tried to smuggle in contract language we wouldn’t accept (“We accepted all your changes”), and committed a host of unfair labor practices. Although our position seems precarious during the pandemic, the university is more reliant on our labor and Zoom expertise than ever. They have only capitulated to a yearlong truce to avoid another strike during a potentially virtual fall 2020 semester. Without our December strike, we wouldn’t be here.

There were many reasons why student workers at the world’s wealthiest university went on strike. Our stipend, which is subject to unexpected changes, barely keeps up with the cost of living in Cambridge; we lack year-round mental health resources, dental coverage, and childcare support. But if you stopped to talk to strikers on Harvard’s picket line, you might have noticed something surprising: the most pressing issue for many picketers was not low pay or inadequate healthcare, but the university’s handling of sexual harassment cases.

Thousands of our members and supporters braved 30-degree weather to march across Harvard Yard, “UAW On Strike” signs draped over our bodies. “Harvard, pay your working scholars,” we chanted, the snow hitting our faces, “You’ve got 40 billion dollars!” Our strike lasted twenty-nine days—one of the longest higher ed work stoppages in recent memory—cancelling final exams, deferring grading for fall courses, slowing down research, and shutting down administrative buildings. Other unionized workers refused to cross our picket lines and halted business with the university, leaving trash uncollected, deliveries stalled, and events uncatered.

The strike came nineteen months after we had first voted to unionize as part of United Auto Workers (which represents over 80,000 academic workers nation-wide). Harvard was still not budging on our demands, and we had exhausted our options. We decided to walk off the job, joining a series of student worker strikes at Columbia, The New School, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the University of California.

The new wave of labor organizing arrived at American universities on the heels of another kind of mobilization: undergraduate sexual assault activism. Years before the Harvey Weinstein revelations opened the floodgates of #MeToo, Emma Sulkowicz was carrying her mattress, The Hunting Ground was streaming on Netflix, and sophomores were spending the holidays explaining “consent” to their parents. Caught in the crossfire of angry students, Obama administration directives, and the attendant right-wing outrage, universities proved largely inept at navigating the new cultural terrain—and even less equipped to handle the skeletons that began to emerge from their closets as the #MeToo movement picked up steam.

Today’s picketers are the same students who developed a new vocabulary for sex, power, and institutional accountability in their undergraduate years, before witnessing the election of a president accused many times over of harassment and rape. So perhaps it shouldn’t come entirely as a surprise that, as the academic labor movement has picked up steam, we have found ourselves relying on a somewhat unlikely tool: the language of #MeToo.

At Harvard, we have been riding the #MeToo wave. In February 2018, just months before our union election, news broke that Government Professor Jorge Domínguez had sexually harassed as many as eighteen undergraduate and graduate students over the course of thirty years, unchecked and enabled by the university. Just over a month ago, The Crimson reported that three prominent Harvard anthropologists face allegations of sexual harassment.

While our union wasn’t overwhelmingly popular from the start, support grew tremendously as we centered our messaging on the Dominguez case, sexual harassment and assault protections, and the possibility of third-party accountability for the university. In March 2019 our “Time’s Up” rally, (borrowing the Hollywood slogan) gathered hundreds of students to deliver a petition signed by more than two thousand student workers asking for a contract with harassment and discrimination protections. By far the biggest mobilization in our campaign up to that point, it laid the organizational foundation for the strike. Several organizers have confided in me that the event was what “radicalized” them, inspiring them to join or take an active leadership role in the union campaign.

Harvard’s protocols for dealing with sexual harassment have left much to be desired. As is the case at many other universities, an army of Title IX coordinators handle the intake of reports. The miscarriage of justice starts in these offices, where students are frequently discouraged from speaking up (“maybe you should wait until you get tenure”) and at times even misinformed about their rights. If a student chooses to file a formal complaint with the Office of Dispute Resolution, university employees conduct an investigation, issue a finding, and recommend a remedy. Their fumbled attempts at handling these cases have been met with student skepticism and even government reproach. Harvard Law School has been found in violation of Title IX by the Office of Civil Rights, and two other Harvard schools are currently under investigation.

The university responded to these legal challenges and students’ lack of trust in its Title IX procedures by launching task forces and holding summits. Last spring, Harvard staged an elaborate “Summit for Gender Equity,” replete with a mollifying catchphrase (“Harvard Hears You”), free T-shirts and canvas bags, and a panel of celebrities including Laverne Cox and Christian Siriano. But this spending failed to purchase trust: The most recent survey by the Graduate Student Council revealed that students overwhelmingly believe the Title IX Office’s first priority is protecting the university’s image—all optics and no justice.

A contract presented a unique opportunity to redress these wrongs and to provide student workers with stronger protections against sexual harassment as well as other forms of discrimination. These measures include having a union advocate assist the student worker throughout the university’s often opaque internal processes, giving the union an opportunity to identify patterns of harassment at the university, instituting interim accommodations, enabling the student worker to continue working while the university is handling the case, and safeguarding victims from retaliation by the perpetrator or other university employees. Most importantly, we wanted a neutral third party to adjudicate harassment and discrimination complaints. This external pressure would push the university to conduct investigations without delay and settle on fair remedies. These benefits would extend to the whole community, undergraduates included, because they would foster a safer campus.

Securing a contract with these measures became a leading issue in advance of our vote to strike, which received the approval of 90.4% of voters, or 2,425 student workers. Within the span of a year, we had gone from winning our union election with a slim majority to organizing a strike with hundreds of workers picketing in the snow for three weeks. It seemed that after years of organizing student workers, many of whom were reluctant to challenge the elite institution they call home, we had found in #MeToo the closest thing to a silver bullet.

But as I look back on the strategy we’ve employed and consider what comes next, I have begun to question just how far #MeToo can take us. Can #MeToo activism sustain our fight for fair working conditions in an increasingly precarious economic environment? Can it push graduate students to conceptualize themselves as members of the working class, and articulate their rights as such? Can it fundamentally change the balance of power in the university?

Last summer, The New Republic declared graduate students “The Labor Movement’s Newest Warriors.” While university campuses, especially in the United States, have been unsteady habitats for radical thought, students have in fact participated in strike actions and formed labor unions since 1969, when the Teaching Assistant’s Association went on strike for their first collective bargaining agreement at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. At public universities, collective bargaining and collective action (including strikes) have won the goods time and again, from healthcare access to tuition fee remissions. But at private universities, building the consensus that student employees even have labor rights, let alone formalizing them in contracts, has been an uphill battle.

Meanwhile, the past few years have seen an acceleration of orchestrated campaigns by right-wing lawmakers, university administrators, the conservative press, and the Trump administration to stave off unionization at universities, most notably in the National Labor Relations Board’s proposed new rule specifying that graduate students at private universities are not statutory employees. Nevertheless, eleven new student unions have won elections (six of them securing contracts) since the Columbia decision of 2016, which reinstated the collective bargaining rights guaranteed to student workers at private universities under the National Labor Relations Act. These gains add up to an impressive membership increase of well over fifteen thousand workers from the academic sector for United Auto Workers, American Federation of Teachers, American Association of University Professors, UNITE HERE, and Service Employees International Union, tracking with an overall rise in labor militancy nationwide. In 2018 and 2019, over half a million workers participated in work stoppages, the highest numbers since 1986, with the majority of strikers in the education sector.

Until recently, NYU was the only private higher education institution where teaching and research assistants were covered under a collective bargaining agreement; such agreements at other private universities including Brown, Tufts, Brandeis, Georgetown, and American have since been negotiated without strikes, but they have not secured robust third-party grievance procedures against harassment and discrimination. The New School, which went on a strike and threatened another, secured these protections.

Aside from harassment and discrimination protections, today’s student employees have taken up the tools of labor organizing in the hope of securing cost-of-living adjustments, eliminating exorbitant student fees, expanding healthcare coverage, and protecting international students from disciminatory policies. While the latter issues fit within the common conception of the labor movement’s goals, a harassment and discrimination-free campus is less traditionally recognized as unions’ bread and butter. Yet it has become increasingly central to our narrative largely due to students’ hesitance to participate in a unionization effort overtly styled as class struggle.

This is not to say that student workers don’t believe in unions, or in class struggle. At a time when four in ten Americans prefer socialism to capitalism, Harvard’s graduate students are hardly untouched by the rising red tide. They think, by and large, that workers deserve protections from abusive bosses and greedy corporations, and they might even go so far as denouncing billionaires. They’re reluctant, though, to see themselves as workers, or acknowledge the degree to which the most ruthless apparatuses of capitalism have infiltrated the private university.

Every union organizer recognizes the stale, familiar rejoinder to their efforts: “I support unions, but…” Some, especially in the sciences, see their graduate education as a stepping stone to all-but-guaranteed professional success. A Harvard degree represents tremendous opportunity, and gratitude to the institution runs deep. Those with more uncertain job prospects, on the other hand, can view their Ph.D. as both an apprenticeship and a chance to pursue an intellectual passion project—and low pay as the price of that creative labor. “Don’t you think we’re being greedy?” they often ask, until they’re forced to shell out thousands of dollars for a root canal, burn through their limited allotment of therapy sessions, or face down unemployment in the sixth year of their Ph.D. program with little to no savings in the bank.

Today’s student workers—through a combination of inherited misconceptions about unions and the nature of their work—view themselves as worlds apart from the stereotypical blue-collar union worker and therefore ill-suited for the labor movement. Many prefer to see themselves as pursuers of knowledge, an intrinsically valuable good (i.e. not a commodity), and members of a rarefied club (i.e. the ivory tower), in line to assume an elite status in society. Yet a precarious material reality threatens to puncture many of these persistent, wrong-headed assumptions.

Like many elite universities, Harvard resembles a 19th century factory town. The university serves as the employer, the landlord, and the healthcare provider for many graduate students, to the extent that those with outstanding bills from the university dental clinic can be prevented from walking at commencement. The Harvard graduate student annual pay comes in at around $22,000-40,000; in years when the endowment doesn’t perform as expected, graduate students’ annual raises are subject to unpredictable cuts. During the 2008 recession, many graduate students at Harvard and elsewhere faced pay freezes for four years or more. Meanwhile, it’s common for landlords in the area to raise rent annually by $100-200 per room, adding up to 3-7% of our pay. The university health plan doesn’t offer subsidized coverage of dental, vision, or dependents, the cost of which can fluctuate. Between 2018 and 2019, adult dependent health insurance premiums were raised about $600 to $7,718—roughly 20% of our wages. Paid parental leave is not on offer, forcing parents to go back to work immediately after giving birth. In the later years of the PhD, the university no longer awards tuition remissions or premium coverage to doctoral students, and their salaries depend on whether enough students enroll in the classes they’re slotted to teach. If a class is cancelled, they’re faced with the choice of taking out loans or looking for another job.

After sustaining this lifestyle for the four to eight years it can take to complete a PhD, there’s no guarantee of a more secure future—or of a future in academia at all. Post-graduation, some of these employees will face an academic job market that has shrunk significantly since 2008. More than half will be hired into dreaded non-tenure-track positions if they choose to stay in academia: since the 2008 recession, the number of full-time contingent faculty positions has grown by 11% (and part-time by 18%), while tenure-track positions have grown by just 1%, with one in three adjunct faculty living below the poverty line. Today, 73% of faculty positions are non-tenure track. In my field, Philosophy, there are about 500 fewer job openings per year than there were before 2008. STEM students, by contrast, often have the option of going into industry jobs to avoid the financial insecurity and the toxic culture of academia. It makes sense, then, that the student workers in the humanities are easier sells on the union than those in STEM fields. With an increasingly low likelihood of attaining tenure—and increasingly high chances of being siphoned off into a bleak market for adjuncts—those of us in the humanities simply cannot afford not to recognize our labor as labor.

Already, the economic fallout of Covid-19 is being felt by academic workers. Job offers have been rescinded, and many universities immediately instituted freezes on faculty salaries, searches, and hiring. Tenure-clock stoppages, which push back promotion reviews for tenure-track faculty, were announced early on, but similar financial protections have not been granted to non-tenure track faculty or graduate students. In an email, Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Claudine Gay told these workers—who cannot access archives to finish their dissertations, whose families are facing bankruptcy, whose spouses are essential workers, whose children are out of school—that it would be wrong to “unduly privilege the current generation at the expense of the next.”

In the context of an ultra-competitive job market and a university scrambling to adjust to remote learning, students are understandably cautious about creating rifts with faculty members and advisors, whose recommendations can make or break their careers. Tenured or tenure-track professors at private universities, unlike some of their public university counterparts, do not enjoy collective bargaining rights under the National Labor Relations Act. Harvard reminds its faculty that they are “officers” of the university, and part of management, sending emails about the need to “protect the university’s academic mission.” This dog-whistle preys on faculty members’ fears that a union would threaten their power. With the Trump administration threatening to slash federal funding, the endowment subject to new taxes, and admissions policies under scrutiny, Harvard has styled itself as an avatar of liberal resistance under siege. To strike, some felt, was to undermine the university at a moment when it served as a crucial bulwark of higher education, research, and the pursuit of truth. This proved a persuasive line of argument because many students remain committed to a rosy view of the university’s core principles and ideals.

At the bargaining table, the university administrators painted a picture of an unfortunate situation: funding PhD students is incredibly costly to the university and brings in no money. In fact, the university runs on graduate students. Research and teaching, which account for 39% of Harvard’s total revenue, rely heavily on student worker labor. Labs are run entirely by postdocs and research assistants, and close to 30% of instructional labor is placed on graduate students. Graduate students grade most undergraduate papers and tests, which enables professors to devote their time to research and writing. Most faculty members don’t know how to use a projector or online grading tool without a teaching assistant’s support—much less navigate the new logistics of remote learning. To put it simply, the university cannot continue to be a research university without our labor.

Harvard’s budget, administrators argued even pre-Covid, was already stretched thin. Our big disagreement often seemed to be about what a private university is: a business with an education wing, or a home of teaching and research?

A quick look into the finances of a private university reveals some ugly truths. Harvard has a $40.9 billion endowment, which it refuses to divest from fossil fuels or the prison-industrial complex, despite an active student movement. It accepts donations from billionaires with ties to Big Tech and Big Pharma. In the wake of the latest scandal, involving Jeffrey Epstein’s donations to MIT and Harvard, both universities pledged to review their donation processes and give money to organizations fighting human trafficking. Even so, Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler Museum continues to attract visitors, and the university deploys its police department at Black Lives Matter protests.

The big-ticket items on Harvard’s budget are equally telling. The university is engaged in costly construction projects that are actively displacing local communities and gentrifying Boston neighborhoods. Harvard puts money into shiny new buildings rather than the teaching and research that earns it its reputation and the academic workers who realize its academic mission. Early on in our bargaining sessions, the university explained it did not have enough money to meet the union’s demands, citing among other things the construction of a new student center, open to the public, that features a living plant wall of 12,000 plants and 19 species, including Japanese ferns, red marantas, and literal “money trees.” Since then, union organizers have joked about stealing plants to pay for dental insurance.

Harvard’s highest governing body is the Harvard Corporation—“the oldest corporation in the Western Hemisphere”—which comprises twelve members, many of whom are corporate executives. Harvard presidents and provosts have served on the boards of corporations during their terms and afterwards. The last president, Drew G. Faust, who began her career as a historian of the Civil War, transitioned seamlessly to the Board of Directors of Goldman Sachs. This is a fitting trajectory for the class of university administrators who act more as guardians of capital than of learning and inquiry.

As private universities drift further away from their core missions, academic worker solidarity is necessary to tip the scales of power away from administrators, wealthy donors, and corporatized governing boards. To save education and research, this line of argument would suggest, private universities have to be governed by workers. A private university with a fully unionized academic worker class can not only improve working conditions, but help determine the agenda of the university.

But to fight private universities’ transformation into hideouts for corporate interest, we need the vocabulary and the willingness to mount an ideological critique. We must reject the idea that a university controlled by boards and donors can protect the academic independence that is so critical to our scholarship. We must conceive of our organizing as class struggle—as a fight not only to win harassment protections, but also to reclaim the university and preserve the integrity of our work. The moral rage of #MeToo propelled our movement into a strike and delivered us our first tentative agreement, but #MeToo alone cannot remake the university.

Articulating a broadly socialist vision for a university may go above and beyond #MeToo, but it doesn’t go beyond the purview of the feminist movement. Despite the complex historical relationship between organized labor and gender equity—not to mention sexual harassment and assault—unionization movements outside of higher ed, including hotel workers, tech workers and media workers, are beginning to organize around feminist platforms. Amidst a national uprising, organized labor is responding to calls to take on police brutality and systemic racism, guided by feminist abolitionists.

Unionization is a natural feminist tool because it provides a pathway to contractual rights like an independent grievance procedure, but at the end of the day such procedures are band-aids (even if they are very strong ones). The question that feminists face within the context of university labor organizing is whether they’re willing to fight for more. Can feminism mean an emancipatory ideal beyond basic accountability for workplace discrimination?

In their manifesto “Feminism for the 99%” Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser define “equal opportunity domination” as the ideology that asks “ordinary people, in the name of feminism, to be grateful that it is a woman, not a man, who busts their union, orders a drone to kill their parents, or locks their child in a cage at the border.” This formulation of liberal feminism pervades the administrations of our elite universities and poses no structural challenges to the capitalist, corporatist, imperialist status quo. “Feminism for the 99 percent,” by contrast, is “a restless anticapitalist feminism”—a holistic political philosophy that includes climate change, racism, xenophobia, and class oppression among its targets and does not ignore the possibility that in an unjust system, women can be oppressors too.

Unions are inimical to equal opportunity domination by nature: the premise of collective bargaining is sharing power. But some unions are quick to compromise: negotiating only standard bargaining subjects like wages and healthcare, allowing restrictive “no-strike” and “management rights” clauses into their contracts, and forgoing adversarial activities like strikes. Such unions limit themselves to redressing strictly circumscribed complaints, passing up the opportunity for radical education and systemic change.

The recent wave of teachers’ strikes (in Wisconsin, West Virginia, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Chicago) have seen teachers campaigning not only for better working conditions but also around broader social and political issues like gun control, ethnic studies curricula, and resisting ICE. These educators have the right theory of power to emancipate themselves from unfair conditions, and they are willing to use that power to tackle other forms of oppression.

At their core, our union’s demands push to remake the political economy of the university alongside an unabashed feminist agenda. Our strike was powerful, but it hasn’t yet accomplished that aim. In many ways, HGSU-UAW has achieved the unimaginable: winning an NLRB election, recognition, and a two-year contract fight—the first union to overcome all of these challenges since the Columbia decision, with one of the biggest bargaining units in the student worker movement.

The final round of contract negotiations tested our commitment to our intersectional understanding of #MeToo. We refused to walk back our demand that protections we achieved for sexual harassment and discrimination (specifically the guarantee of interim measures) be extended to cover other forms of discrimination, including racial discrimination. Even under the pressure of recent events, Harvard balked. Ultimately the moral force of the current moment carried us to a tentative agreement with strong protections covering all forms of identity-based harassment and discrimination—but not a third-party grievance procedure.

Foregrounding #MeToo was a deliberate choice that has influenced the way we organize, the way we narrativize our fight, and the demands we bring to the table. But, of course, harassment protections were never our only goal. We fought for a wide array of improvements to our pay, benefits, and working conditions, and we have made real progress: a 2.8% raise, childcare subsidies, dependent health coverage, protections for international student workers, intellectual property rights, and workload limits. At an extremely perilous economic moment, this yearlong contract, if ratified in the upcoming days, will protect us from the worst of pandemic-era austerity. Then, we will resume our fight to get Harvard to match industry standards—not too much to ask, one would think, from a university with a $40 billion endowment.

New union leaders will be back at the bargaining table in less than a year. Organizers will have to build momentum in a new, mostly virtual, workspace, and start enforcing our rights under our first collective bargaining agreement. The success of the movement will depend on our ability to maintain pressure on the administration in an even more hostile environment: our labor rights stripped by the Trump National Labor Relations Board, our research delayed by the coronavirus, and our financial futures more uncertain than ever. But if we have learned anything from #MeToo, it’s that mobilization can become fodder for organization in the hands of labor organizers.

What remains to be seen is whether the #MeToo campaign that animated our strike can be extended into a broader feminism—a feminism for the 99% that is not only intersectional in the liberal sense but also anti-capitalist. In the coming months, graduate workers’ decisions will demonstrate how far #MeToo can drive our movement, and whether we’re ready to take aim directly at the neoliberal university itself.

Ege Yumusak is a PhD candidate in philosophy at Harvard and a member of UAW local 5118.