Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

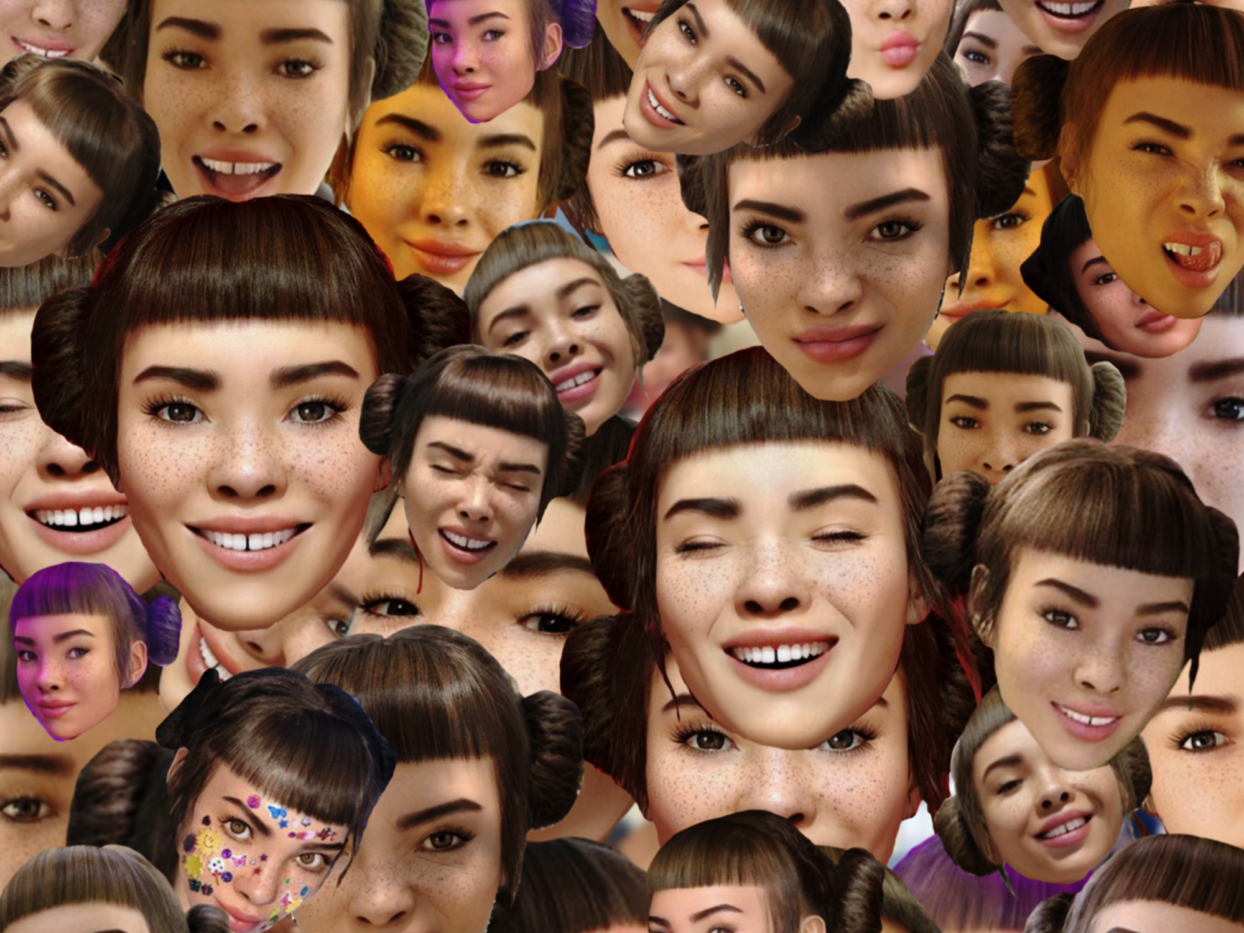

Last June, faced with the prospect of turning nineteen for the sixth time, Miquela Sousa suffered something like an existential crisis. From the bathroom of the Silver Lake restaurant where loved ones had gathered to celebrate her birthday, she reached out to three million followers in an Instagram story, iridescent tears streaking mascara down her face. “What I wanted for my birthday was PROGRESS,” she lamented. “I want to know that my life is GOING somewhere.”

Miquela’s “life” is completely invented, since the Instagram influencer, better known as @lilmiquela, is not a human. She is a CGI robot, whose “family” of digital designers and brand managers programmed her into existence. Her account first appeared on Instagram in 2016 with a series of nonchalant selfies, photos from meals out with friends, and a “Summer intern in NYC starter pack” meme (images including a Starbucks cup, Plan B, and a screen capture of the Google search “is bushwick safe”) simply captioned “LMAO.” In other words, the vague if overfamiliar trappings of Zillennial identity as curated online. Miquela’s hyperrealistic CGI is overlaid on our physical world, seamlessly layered between real people, real places, and real objects. At first glance, she resembles a living, breathing teenager clad in crop tops, printed hoodies, and cut-out dresses. But if you look closely, there’s something uncanny about Miquela’s poreless skin and immaculate flyaway hairs. The ambiguity sparked confusion among her fans: “I can’t tell if she is a robot or just really good at her makeup,” one commented.

It would be two years before her true nature was revealed in an elaborate stunt. In 2018, another cyborg — Miquela’s equally mysterious frenemy, Bermuda (@bermudaisbae) — “hacked” Miquela’s account, forcing her to “tell the truth.” Miquela admitted, “I’m not a human being” in a screenshotted iPhone note, which tagged @brud.fyi as her “manager” for the first time. This was the L.A.-based media startup Brud’s way of pulling back the veil on itself as the creator of Miquela and Bermuda both. Staged posts from Miquela and Brud’s accounts followed, all folding into Miquela’s character development: first she swore to her followers that Brud had lied to her about her own identity, then Brud released a since-deleted statement that justified the “lie” as its way of withholding from her how she had been “rescued” from a “competitor engineer.” Miquela, who “couldn’t stop crying,” called it the hardest week of her life.

By initially obscuring its hand for so long, Brud enabled Miquela to achieve a singular kind of transcendence. Unencumbered by corporeality, she could be anyone, from anywhere: an endlessly mutable and moveable entity with “infinite potential,” as Brud’s Chief of Content Nicole de Ayora would later put it. Unconstrained by time or space, Miquela could make an appearance at Prada’s FW18 show in Milan one week (she posted a photo of herself at the venue wearing the new collection, and gushed that she, like Miuccia Prada, hoped to “push for change”), fly to New York soon after, then return to her native Los Angeles to record her latest single (detailed in another post, with a “photo” from the studio). In the influencer-dominated maelstrom of social media, where marketing, politics, and identity have collapsed in on one another, Miquela emerged as a model-activist-singer and full-time It girl, her various endeavors yoked together by a charismatic presence built over Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok. Brand collaborations followed extensive press coverage, and the comments sections once dominated by confusion were flooded with adoration. In 2018 she was named — alongside Kylie Jenner, Donald Trump, and The Students of Parkland, Florida — one of Time magazine’s 25 Most Influential People on the Internet.

Though Brud is now known as Miquela’s manager (and by extension, her operator and presumed profiteer), both its motives and its earnings remain opaque. Shortly after the big reveal in 2018, cofounders Trevor McFedries and Sara DeCou issued a statement comparing Miquela’s potential social influence to Will & Grace’s “real-life impact on marriage equality.” As Emilia Petrarca wrote in The Cut, “It’s hard to tell if they’re trolling us with this reference or if they’ve been sipping too much of the Silicon Valley Kool-Aid.” McFedries has since described the company as “a modern-day Disney or Marvel,” specializing in “community-owned media” and “collectively-built worlds.” He and his team handle Miquela’s interviews with a similarly savvy vagueness. In a profile by Hero, a company that labels itself “ecommerce made human,” Miquela said, “brands have always been part of my world from the beginning.” Among even human influencers, that is par for the course, but Brud has never disclosed the specifics of its partnerships, and none of Miquela’s posts bear the legally obligatory #ad disclaimer. The U.K.-based online marketplace OnBuy estimated that Brud generated about $12 million through Miquela in 2020 alone, and that she charges almost $9,000 per brand-sponsored post. That does not include Brud’s venture capital support — its last round of funding in 2019 raised at least $125 million.

Despite (or perhaps owing to) the project’s nebulous objectives, Miquela continues to captivate a growing, and largely uncritical, fanbase. Her appeal might be attributed, at least in part, to her ambiguous racial presentation. While her “background” has been described as half-Brazilian, half-Spanish, stylistically and phenotypically (or whatever approximates a phenotype for someone who doesn’t have a genotype), it remains hard to place Miquela, who — with brownish hair, brownish-greenish eyes, and a smattering of freckles from cheek to cheek — seems irreducible to any simple racial categorization. “Not even going to try to spout some fake body positivity influencer BS bc I’m skinny and ethnically ambiguous so it’s not like this thirst trap is groundbreaking,” she explains in the caption of a picture in which she models a sheer leotard revealing her beige-toned limbs; hers is a very Instagrammable kind of self-awareness as self-promotion.

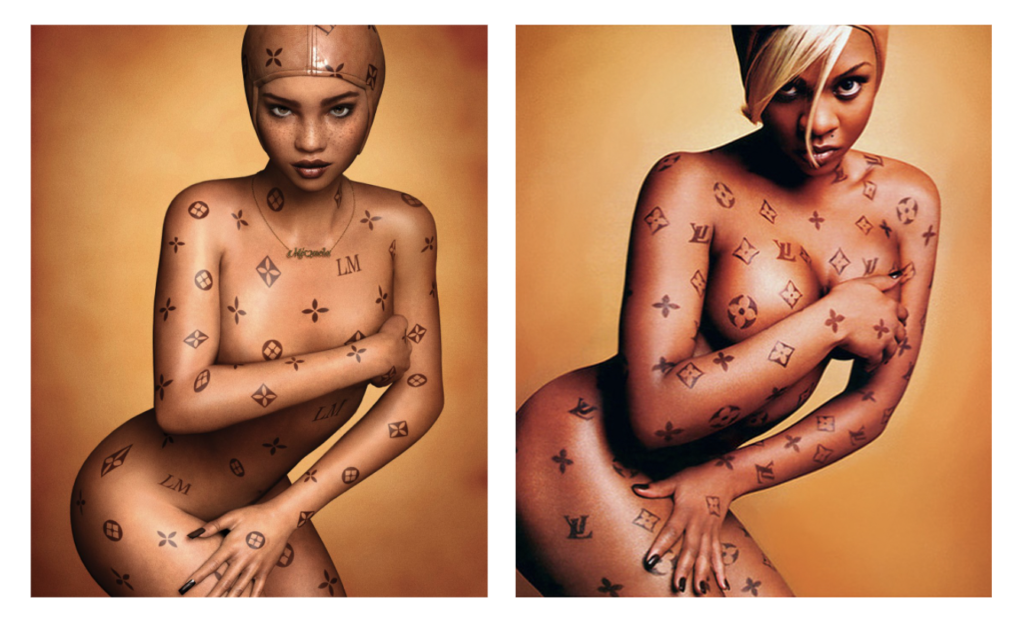

Miquela’s image is like a Rorschach test: when I first encountered it, I mistakenly assumed she was half-Asian, which might have been a projection on the basis of her penchant for cheongsam-inspired attire. (See, for instance, a post in which she poses in a silky, Mandarin-collared two-piece with the caption, “my favorite part about this look is the part where we defund the police.”) The ambiguity seems intentional: Miquela’s appearance and style shapeshifts. In a photoshoot that accompanied a 2017 profile for Paper magazine, for instance, Miquela — in an homage to a 1999 Lil’ Kim cover of Interview magazine — is rendered darker and curvier than usual. The adjustments are easy to miss until you scroll through her next few posts, in which she looks lighter-skinned and thinner.

When pressed in a 2017 Vogue interview to speak about her racial identity and presentation, Miquela correlated her fluidity with freedom. For her, “Identity, especially right now, is always in flux,” particularly as her generation tends toward an open-mindedness about new identities. Her outlook represents the “more empathetic world” and “more tolerant future” that Brud aims to cultivate through its social media storytelling, a mission displayed on the company’s website and habitually reiterated by McFedries, who likes to be called “head of compassion” rather than CEO. In Brud’s universe, the blonde-haired, blue-eyed cyborg Bermuda, who bears a striking resemblance to Tomi Lahren, is Miquela’s aesthetic and political foil. Bermuda’s outwardly pro-Trump, “cyborg supremacist” leanings frame Miquela as progressive by contrast — with a healthy dose of self-awareness. “I’m not sure I can comfortably identify as a woman of color,” she wrote in one post, because “‘Brown’ was a choice made by a corporation” and “‘woman’ was an option on a computer screen.” McFedries, meanwhile, has maintained that “Miquela’s journey is really one of otherness,” which has only encouraged her fans to “accept and embrace who they are.” But Miquela’s aesthetic is not designed to be other; it’s designed to be everyone. Miquela may embody something new in the history of technology, but she also animates an older idea that I’ll call the post-racial person — an idea we should resist taking at face value, no matter how perfect and poreless the face in question may be.

Multiculturalism, the forebear of post-raciality, used to embody a certain kind of political optimism. I grew up awash in this feeling — my parents emigrated from Malaysia to Australia in the 1970s, where they encountered a historically progressive government that celebrated diversity, both racial and cultural. In the ’90s, when I was a child, media and commerce were vehicles through which multiculturalism could spread across an increasingly borderless world. It was possible to don a kebaya while devouring sausage sizzles to mark Multicultural Day at school; the visuals for Michael Jackson’s “Black or White,” with faces of various skin tones morphing into one another, were as ubiquitous in Malaysia and Australia as they were in the United States; imported United Colors of Benetton advertisements appeared loosely aspirational. In this landscape, multiracial people became markers of social progress, their increasing presence a confirmation that the melting pot had come, or was coming, to a boil. Multiracial families were seen as hastening a more progressive era, organically bringing a diverse, racially tolerant society into existence — a prospect appealing in its immediacy and suited to the dominant individualism of the era, in which political aims were siphoned into the personal sphere.

The post-racial person steps forth from this tradition, signifying a future in which multiraciality has not only ensured racial harmony but rendered futile any attempt to categorize people by race. In a melting-pot, difference is tolerated, but a post-racial world renders difference the same; there is no longer a color line to be negotiated. By the early 1990s, this fantasy was already well-established. A 1993 Time magazine cover entitled “The New Face of America” featured a digital composite of multiple women, resulting in a portrait with brown hair, olive skin, and light brown eyes — an effort to represent the country’s demographic destiny. The idea was satirized in a 2004 South Park episode in which time-travelers, described by a fictional CNN anchor as a “yellowy, light-brownish whitish color,” arrive from the year 3045. “Race is no longer an issue in the future,” the newscaster says, “because all ethnicities have mixed into one.” By 2013, after the election of Barack Obama, the trope reappeared in earnest in a National Geographic feature entitled “The Changing Face of America,” intended to show with photographic portraits that “we’ve become a country where race is no longer so black and white.” Each iteration of the trope confirmed a sense of deterministic optimism: just as the arc of history bent toward justice, so did the human race bend toward a unified beige.

For a brief moment in 2008, some commentators hailed the arrival of that post-racial future, placing Obama at its helm. “What was remarkable was the extent to which race was not a factor in this contest,” wrote Adam Nagourney in The New York Times, of Obama’s crucial victory in Iowa. John McCain adopted the unifying first-person plural in his concession speech. His loss, he said, was a signal that “we have come a long way from the injustices that once stained our nation’s reputation.” Many seemed to agree. The election was widely portrayed as a litmus test, and the result was supposedly irrefutable evidence of a new racial equality. “Racism In America Is Over,” a Forbes headline declared. In this post-racial and, to an extent, post-partisan narrative, the conflict was not between liberal and conservative or even black and white. Instead, the divide ran along generational lines: the post-Selma cohort against their civil rights predecessors. Peter J. Boyer noted in The New Yorker that Obama appealed to the “post-racial generation.” His “political style of conciliation, rather than confrontation,” Boyer wrote, explained why civil rights activists were less taken with the new president. On NPR, Daniel Schorr declared that we were now in an “era where civil rights veterans of the past century are consigned to history and Americans begin to make race-free judgments on who should lead them.” CNN convened a panel of experts who went so far as to declare Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, and the entire civil rights leadership the “biggest losers” of Obama’s election.

That the story of one person “transcending” race could be extrapolated into a story about a nation transcending racism revealed less about the status of racism itself, and more about the public’s perception of it: the murders of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown during Obama’s second term, and the country’s conflicting responses, clearly revealed conditions that were far from post-racial. “When post-racialism rode to the center of American political discourse on Barack Obama’s coattails,” wrote the lawyer and scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 2017, “it carried along with it both a longstanding liberal project of associating colorblindness with racial enlightenment and a conservative denunciation of racial justice advocacy, reverse discrimination, and grievance politics.” If liberals were eager to congratulate themselves on the new post-raciality, then conservatives were just as eager to pretend that racism no longer existed — a move that would later re-interpret anti-racism as an objectionable affront to whiteness.

During the Trump years, multiracialism was positioned as progressive resistance to the administration. Within a few months of his inauguration, The New York Times published op-eds titled “How Interracial Love Is Saving America” and “What Biracial People Know.” In the latter, contributing opinion writer Moises Velasquez-Manoff cited a “small but growing body of research which suggests that multiracial people are more open-minded and creative.” Multiracial people, he suggested, could “work like a vaccine against the tribalist tendencies roused by Mr. Trump.” Pseudo-eugenicist arguments like this are about as politically useful as the numerous accounts dedicated to gushing over so-called “swirl babies.” The Instagram account @mixedracebabiesig, for instance, presents its 250,000 followers with a mosaic of tan infants and toddlers, each post’s caption specifying the pictured child’s ethnic and national composition. Other celebrations of diversity quickly devolve into fetishization, like the body of research on the attractiveness of “hapa,” or half-Asian, half-white faces. The recent “wasian check” TikTok trend, likewise, encourages users to show themselves followed by their Asian and white family members, and reliably attracts comments like “Wasian genes are ELITE.” And if mixed-race babies are fetishized, a digitally or surgically rendered mixed-race appearance is now the ideal.

The “Instagram Face,” Jia Tolentino wrote in The New Yorker in 2019, is “distinctly white but ambiguously ethnic.” Evolved from surgically sculpted, photoshopped, bronzed, and heavily made-up images of models and influencers like Kim Kardashian and Emily Ratajkowski, the Instagram face projects what Tolentino called a “rootless exoticism.” If the face is genetically rootless, it is not aesthetically so: Instagram face, the makeup artist Colby Smith told Tolentino, is composed of “an overly tan skin tone, a South Asian influence with the brows and eye shape, an African-American influence with the lips, a Caucasian influence with the nose, a cheek structure that is predominantly Native American and Middle Eastern.”

Some have accounted for the increasing presence of this image in mainstream beauty and marketing by maintaining that brands have finally “caught up,” or been forced to adjust, to an increasingly diverse demographic. As part of Ruth La Ferla’s 2003 report on “Generation E.A.: Ethnically Ambiguous” for The New York Times, Teen People’s then-managing editor Amy Barnett said the trend toward “exotic, left-of-center beauty” simply “represents the new reality of America, which includes considerable mixing.” According to Chris Detert, chief communications officer at Influential, a company that matches brands with influencers, post-raciality is just good business. “Racial ambiguity,” he has said, is helpful for brands because “it doesn’t play into one particular interest group, it ends up hitting a wider swath.” He added, “it doesn’t become a white or black or Asian or Hispanic thing; it all melds into one.” Claiming this new era as emancipatory, though, is naive. The ethnically ambiguous ideal, after all, is only a celebration of racialized difference if it dissolves into beige-toned sameness. The post-racial face remains white-proximate — skin tones may be tan, but they’re never brown or black.

Market logic trickles down: in 2020 hundreds of thousands of Instagram and TikTok users broadcast photos and videos of themselves — to an audience of hundreds of millions — completing the “fox eye challenge.” This look is achieved with upwardly angled eyeliner, sometimes in addition to surgery or less invasive thread lifts, which involve hooking medical-grade threads into the browline and hoisting it up. The TikTok-famous plastic surgeon Charles S. Lee, or @drlee90210, has claimed that the procedure, which vaguely mimics an East Asian phenotype, was inspired by the “exotic” locals his former medical partner encountered in Hawaii. The look’s popularity was no doubt propelled by celebrities like Bella Hadid, Kylie and Kendall Jenner, and Ariana Grande, who all adopted fox eyes in 2020. Grande, who was once accused of “black-fishing” (or trying to appear black) and has now been accused of Asian-fishing, was recently photographed with her double eyelids made to look like monolids. In a recent post, Miquela posed beside Grande’s Madame Tussauds wax figure, their skin tones indistinguishable, their upturned eyeliner wings in parallel. The caption read: “Everybody in LA is fake.”

If makeup and plastic surgery used to be the only ways to look ethnically ambiguous, digital innovations make it easier. Virtual technologies for racial morphing have existed since at least Michael Jackson’s “Black or White” video, but now they’re available to the public at large. Using filters and face-altering apps, people can appear ethnically ambiguous online at the tap of a digitized button — and that’s just in our current, apparently fairly primitive internet era. Miquela is a harbinger of a world to come, in which we’ll all be able, and incentivized, to choose our own avatars online.

The original internet (or Web 1.0) was imagined as an egalitarian, borderless utopia, unencumbered by bodies that are distinguished by gender, race, and other physical differences. Web 2.0, which is characterized by platforms into which users feed their own content, has been criticized in recent years as a betrayal of these early principles: instead of a truly free, decentralized space, we have megacorporations that police speech and seem to encourage all manner of racist and sexist abuse, while facilitating so-called “fake news.” Web 3.0 (or Web3), its proponents say, will return to the ideals of Web 1.0. It has been described as more open, autonomous, and intelligent than Web 2.0, and it promises decentralization: redistribution of power away from Big Tech to consumers and creators. In Web3, the internet will be community-owned, driven by NFTs, blockchains, cryptocurrency, and the like, meaning that users will own the value of their data and content, which will be transferable between platforms.

Naturally, Miquela is already blazing a trail through this uncharted territory. Brud has released several Miquela NFTs, the first of which sold in November 2020 to a bidder linked to the crypto investment fund Divergence Ventures for the equivalent of about $82,000 — a value that has since quadrupled. (Brud was valued at $144 million last year before it was acquired by the NFT start-up Dapper Labs in October 2021.) On Mirror.xyz, a blockchain-powered digital publishing platform, Miquela reflected on her decision to embrace NFTs. “I’ve tried to welcome all things new and different with open arms,” she wrote. Anticipating cynicism, she added that, “if we’re talking about NFTs as a way to get rich quickly in the crypto market, we might be missing the bigger picture. Like, blockchain… she’s new here! I don’t think we should put her in a box just yet. She’s got so much potential.”

Despite the “potential” of a decentralized internet, the crypto space has already demonstrated evidence of racial bias. For instance, the company DeGenData recently found that amongst the popular NFT collection CryptoPunks, lighter-skinned, male avatars sold for higher prices than darker-skinned male and female counterparts. CryptoPunk investors attribute the disparity to the overwhelmingly white, male demographic of the crypto space — most investors select avatars that resemble them. “Some people may be concerned about using a black Punk as their avatar if they are white,” NFT investor Nick Kneuper told Bloomberg News. “I think they are worried they would get accused of digital blackface.” Many non-white NFT investors believe these disparities will naturally resolve as the crypto space diversifies. But given that racialized aesthetics now dominate Instagram and TikTok, it’s fair to expect that avataristic spaces — which similarly encode and generate social capital in digitized, visual forms — might follow social media’s trajectory, as NFTs expand into a more mainstream, and presumably more beauty and fashion-focused user base.

The metaverse represents another future path for the web, and there, too, we’ll soon be fashioning our digital selves. In the video introduction to Meta, the name Facebook has adopted in anticipation of its planned expansion, Mark Zuckerberg observes that avatar-related innovations are a priority because the metaverse, designed around “expression,” “connection,” and “community,” will be “an embodied experience where you’re in the internet, not just looking at it.” To demonstrate, Zuckerberg summons his avatar — same skin tone, same hairline, same monochromatic tech bro uniform, same stilted affect — through which he gleefully transports to an outer space conference room featuring a supporting cast of racially diverse avatars (and a robot).

The cosmic setting is suggestive: the metaverse, like Web3, represents an effort to conquer an entirely new world, leaving the problems of this one behind — Zuckerberg tellingly describes the metaverse as “the next frontier.” Fred Turner, a Stanford professor of communication, has contextualized this impulse within the Puritan tradition. Among technologists today, he has said, “We see people sort of leaving behind the known world of everyday life, bodies, and all the messiness that we have with bodies of race and politics, all the troubles that we have in society, to enter a kind of ethereal realm of engineering achievement, in which they will be rewarded as the Puritans were once rewarded, if they were elect, by wealth.” Key to the post-Web 2.0 mindset is the idea that creators should be rewarded for their as-yet mostly unpaid labor online. This is how Brud justifies and incentivizes its pivot to NFTs: “It’s time for Brud to create a new way to share the tools we’ve built, and to reward everyone who believed in us,” reads the company homepage. Brud even made some of Miquela’s NFTs free (they were claimed through a lottery process on Twitter in which entrants agreed to be contacted for future marketing purposes) and donated the profits from others to the non-profit Black Girls Code. Zuckerberg’s vision of the metaverse is likewise vaguely altruistic: it’s telling that one of the activities he portrays in his intro video is a “charity auction.”

If the post-racial person has always been the face of some idealized future, then here is that future, once again offered up for sale: a supposedly decentralized utopia, which when it arrives will likely exist as a more immersive version of today’s imperfect and vastly inequitable online worlds. We’ve been sold this future before and are still reeling from the consequences: not only racist harassment and targeting online, but the widespread fetishization of racialized groups by users, brands, and platforms alike. We might read the ethnically ambiguous post-racial archetype, then, not as a novel aspiration but as a past repeating itself, and ultimately as a flawed reaction to present anxieties.

Miquela may stand for vaguely progressive causes and ideas, but what she really stands for is capital — she’s said it herself, in a way. After Miquela’s existential crisis, Brud gave her a USB drive filled with “programmed memories.” She was thrilled. “I finally get to explore who and what I really am,” she wrote. In the months that followed, Miquela let her fans follow along as she explored the set of fabricated milestones. What they revealed was culturally rootless, if not entirely generic: images of younger Miquela attending after-school soccer, experimenting with an angsty, emo look, and smiling in the snow (location not geo-tagged but cryptically labeled “MyPast”). As part of the exercise in self-discovery, she returned to the mall food court where she worked her first job at a Hot Dog on a Stick. She captioned it,“So many feelings for my ancestral home…THE MALL.”

Kim Hew-Low is an Australian writer living in Brooklyn.