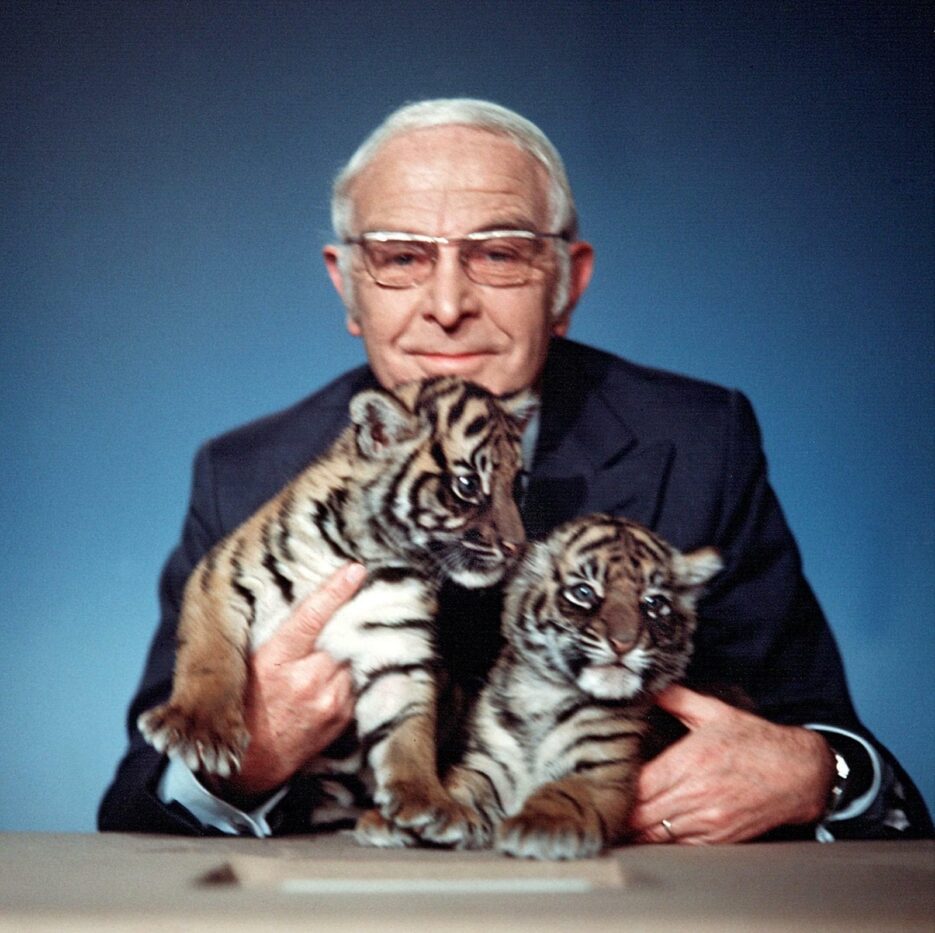

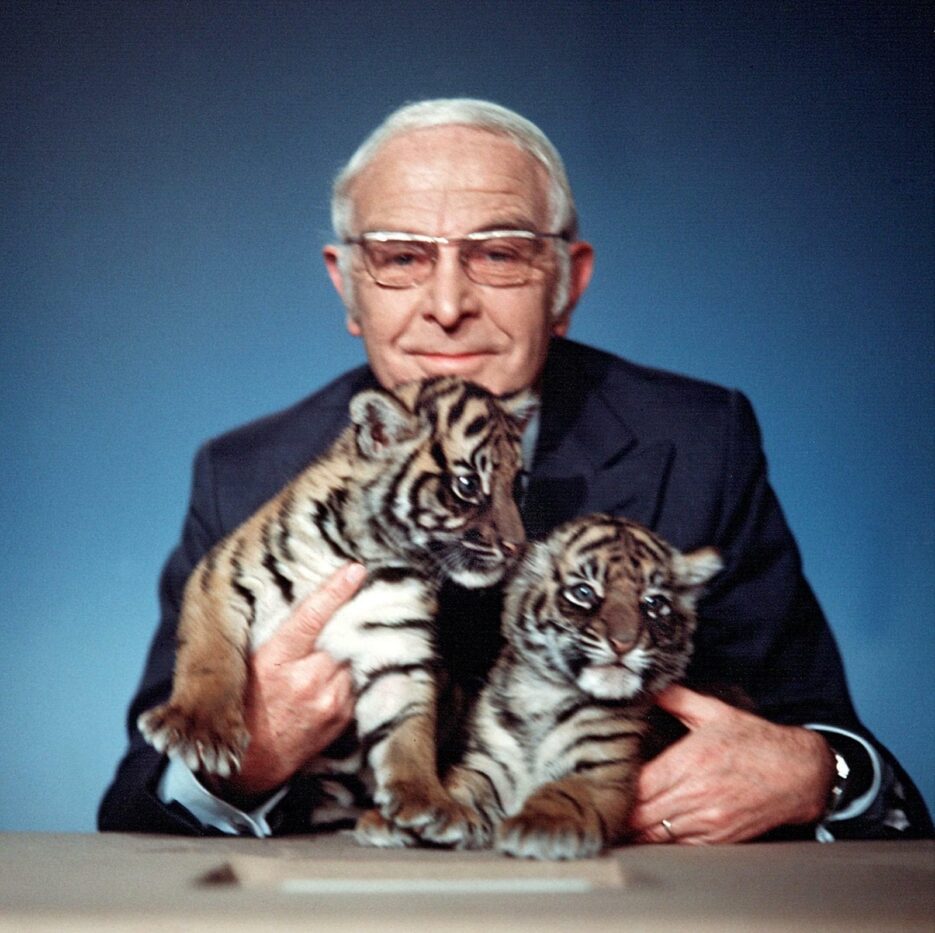

Bernhard Grzimek with tiger cubs ©hr/Heinz-J. Schlüter

Bernhard Grzimek with tiger cubs ©hr/Heinz-J. Schlüter

Google “nature’s revenge,” and the internet free-associates straight to Covid-19. The first several search results read like a back-and-forth debate: coronavirus does, or else it doesn’t, represent an ecological spin on divine retribution. The pope has an opinion on the matter, as does the lead guitarist from Korn.

Also in the fray is an organization called The Turtle Conservancy, which weighed in decisively with a March 26 post titled “Mother Nature’s Revenge: Covid-19.” Like other wildlife protection groups, The Turtle Conservancy has long lobbied against the wild animal trade. And like everyone, the group has found its preexisting principles vindicated by the current crisis: it calls for the immediate abolition of wet markets like the one in Wuhan where the coronavirus is suspected to have made the “jump” from bats to maybe some intermediary species to humans.

For Turtle Conservancy President and CEO Erik Goode, nature’s vengeance was opportunely timed: Tiger King, the Netflix documentary series he co-directed, was in the midst of a runaway success, thanks in part to the fact that a horde of “non-essential” Americans were newly couch-bound. The series was released exactly a week after the initial shock of U.S. restaurant closures and shelter-in-place orders—the first event in my lifetime (the first since probably World War II) to radically upend daily routines for nearly everyone in the country, not to mention the rest of the world.

Thirty-four million households would likely not have tuned in, on that particular week, for an earnest exposé on the mistreatment of tigers in the roadside zoos that dot the Southern landscape. But Tiger King is not particularly conservation-minded. It features a sex cult, a presidential run, and multiple murder schemes. Despite a few perfunctory nods toward the inhumane treatment of wild animals in American captivity, the show is less about cruelty to tigers than the bizarre human social formations occasioned by cruelty to tigers.

From the first episode, the series sets up a showdown between bad-boy animal abuser Joe Exotic and too-righteous animal rights activist Carole Baskin. Both keep tigers on similarly named properties, and though hers is nonprofit and his anything but, Tiger King establishes a moral equivalency between tiger conservationists and tiger collectors. In the show’s bleak worldview, there are no healthy relationships to wild animals. Only obsession, sublimation, exploitation. What compels these eccentrics? the show wants you to ask. What are they projecting onto the tigers? Why, deep down, do they care so much about these animals?

Tiger King premiered in a time of cultural consolidation: everyone was having the same conversations, reading the same news updates. Ninety-two percent of U.S. adults reported following coronavirus news “very closely” at the end of March. By coincidence, we were watching the show at the same time we were researching wet markets and sharing photos of wild animals intruding on urban spaces—but Tiger King was being used to escape, not to think through, the crisis.

Critics, perhaps desperate for an object of analysis less demoralizing than the crumbling of the federal bureaucracy, pounced on Tiger King. Did the show do enough for conservation? Was it sexist, sensationalist, or unfair? Yet in all the piles of analysis heaped on this not particularly interesting cultural object, no one seemed to notice the blinkered psychology at play: as Americans sequestered themselves from a viral pathology unleashed because humans got too close to wild animals, over ten percent of the American population chose to distract themselves with a trashy docu-series that pathologizes the desire to be close to wild animals.

The wet markets, it turns out, are only a proximate cause, a result less of “exotic cultural practices” than political economy. As industrialized farming pushed small-scale Chinese pork, beef, and poultry farmers into the wild game business, deforestation simultaneously moved virus-harboring bats closer to human populations. What causes deforestation is the same thing that causes industrialized farming—a villain larger and harder to blame than Joe Exotic or Carole Baskin, because it’s always just outside the frame.

Tiger King was treated as a departure from the noble legacy of conservation movies, “the product of a quickly changing film industry in which the lines between documentary and fiction are blurring,” per The New York Times. Erik Goode and his co-director Rebecca Chaikin, it seemed, had not only skewed some facts but also manipulated Baskin into participating by telling her they were going to make a documentary amplifying her cause—abolition of roadside zoos, regulation of the domestic tiger trade—and instead made fun of her clothes and more than implied she had put her husband’s body through a meat grinder before feeding it to tigers.

But blurring the lines between fiction and reality in documentary is as old as documentary itself. From the emergence of the form, documentaries have sought out and fictionalized the most extreme points of contact between “humanity” and “the wild,” not only reflecting back but actively promoting a set of myths that license oppression, extractivism, mass eviction; the histories of documentary, exploitation, and wilderness conservation are darkly intertwined. Transporting us to the wilderness and confronting us with the violence of the unindustrialized world, the past century of documentary output is an archive of fears about human dominion over nature—the sneaking sense that we’ve gone too far, controlled too much, and that the wild might, at some point, bite back.

According to industry lore, the term “documentary” entered the English lexicon to describe the films Robert Flaherty was already shooting in the most remote locations he could access. His first, Nanook of the North (1922), depicts the life of a family of Inuits struggling to survive in the barren, icy landscape of the Belcher Islands in Northern Canada. An early title card sums up Flaherty’s cartoonish primitivism: “here, utterly dependent upon animal life, which is their sole source of food, live the most cheerful people in all the world.” An igloo is constructed, a walrus hunted; the film was a critical and commercial hit, launching the thirty-eight-year-old Flaherty into a vaunted career as chronicler of human subsistence on inhospitable terrain at the peripheries of the “civilized world.” He shot Moana (1926) in Samoa, and Man of Aran (1934) on an island off the coast of Ireland, where, in the film’s climax, the title character embarks on a perilous shark-fishing expedition.

Even then, Flaherty was accused of romanticizing. Ivor Montagu, writing in the New Statesman and Nation, argued that “Flaherty is busy turning reality into romance.” In Cinema Quarterly, Ralph Bond likewise dismissed Flaherty as a “romantic idealist striving to escape the stern and brutal realities of life, seeking ever to discover some backwater of civilisation untouched by the problems and evils affecting the greater world outside.”

By the time Flaherty made his documentaries, the walrus and shark hunts he depicted were obsolete: he had to bring in outside consultants to teach his subjects how to catch their prey. Not particularly wedded to the facts, Flaherty often centered his films around “families,” which he tended to construct out of unrelated locals he happened to find attractive. A woman who played one of Nanook’s wives soon became pregnant with Flaherty’s child. In Man of Aran, he cast Maggie and Michael Dirrane as mother and son, relegating Stephen Dirrane to the role of Canoeman #2 so that the title character could be played by a taller, more chiseled blacksmith—a man who, because history is stranger than fiction, went by the name of “Tiger” King.

Flaherty wasn’t interested in depicting reality. Nor was he advocating for the reversal of industrialization, or even for the industrialized world to leave his subjects’ cultures alone. He was trying to show a way of life that was forever destroyed, lost to history and to capital. He was creating—and reinforcing—a myth.

Besides, Flaherty was in no position to protest development. He had only made it up to the Belcher Islands and started filming because, like his father before him, he was a prospector. He was surveying for mineable ore.

Around the beginning of the pandemic, I was sent the link to a YouTube video documenting a wet market supposedly in Wuhan. It shows a series of wild animals I couldn’t identify impaled on thick skewers. Dogs sit in cages, a massive snake is chopped up on a butcher’s table, and the rib cage of something larger sits on display as shoppers mill about. The wet market is an easy target, I think, because it’s so visual; it allows you to see—or think you’re seeing—an origin story for coronavirus with your own eyes.

That story goes like this: A virus had developed over some indeterminate amount of time, mutating and circulating among horseshoe bats. But the virus was contained, sealed off from human populations, until it hitched a ride to a wet market in Wuhan, where wild animals like bats and pangolins are bought and sold as food. There, the virus had no trouble finding its first human host, and then its second, advancing onward to the city, the province, the country, the world.

This chain of events is accurate, but it’s incomplete, eliding the complex international system whose invisible hand is present in every link. An interconnected world creates the capacity for diseases that might have been localized epidemics to rise to the status of pandemic. Meanwhile, global capitalism has exponentially increased the opportunities for pathogens to spread to humans, even before they can hop on an airplane. Industrialized agriculture, as Rob Wallace has written, breeds disease by homogenizing the gene pool and placing domesticated animals in close proximity, where viruses can spread to genetically similar, equally vulnerable, victims.

At the same time, deforestation worldwide causes habitat loss, which displaces bats and other virus-harboring species. Research has shown that the greatest opportunities for “spillover” are in the places where primate habitats have been depleted. The wildlife trade may hasten these interactions, with millions of animals and hundreds of species trafficked every day. But according to several studies, a virus is likeliest to make the inter-species “jump” in a place where environmental change like deforestation has pushed wild animals closer to large human populations. In recent years, viruses have surfaced in “developing nations” not because they’re insufficiently “developed”—maintaining low standards of hygiene or eating the wrong kinds of animals—but because they’re in the process of development itself.

Avian flu and SARS emerged from Guangdong Province, which became extremely dense with contact between humans and wild animals due to a fast-growing manufacturing sector. The Nipah virus has been traced to bats that, dislodged from their habitats, left saliva in fruit on a pig farm in Malaysia, which belongs to a region that has lost 30% of its forest over the past forty years. In West Africa, the latest Ebola epidemic was likely spread to humans by still more bats whose homes were destroyed for the production of palm oil. Coronavirus fits the pattern: as Wuhan became a manufacturing center, the population sprawled into the forest. Edged out of livestock farming by industrialized agriculture, locals began to hunt and raise wild animals like bats and civets, encouraged by the Chinese government.

The global north has largely displaced the toll of mass-production to the global south, where it mines, pollutes, and chops down trees with impunity. The environmental and health impacts are, in the short term, offloaded. But the effects of CO2 emissions don’t remain in the global south—and neither does a virus like Covid-19.

Capitalism, the theorist Jason Moore writes, “is not an economic system; it is not a social system; it is a way of organizing nature.” A third of the land on Earth is now used for agriculture, and tropical forests are being destroyed at record rates. 83% of wild mammals and 80% of marine mammals have vanished over the course of human history. Today, livestock and humans together account for 96% of the biomass of mammals on Earth. Wild animals make up the remaining 4%. Yet the more we attempt total dominion, reorganizing the animal world to suit our economy, the more clear it becomes that our attempts are self-defeating: that 4% still has the ability to tank the global economy and inflict mass death, largely due to the unintended consequences of human intervention.

The view of nature as external and unlimited—the view that enables rampant deforestation—also gives rise to a catastrophist myth of human history. In Moore’s telling: “Capitalism—or if one prefers, modernity of industrial civilization—emerged out of Nature. It drew wealth from Nature. It disrupted, degraded, or defiled Nature. And now, or sometime very soon, Nature will exact its revenge.”

Back in college, I shot a very amateur student documentary at a five-star safari game reserve in South Africa. I knew from the outset it was an ill-advised, over-ambitious project, but I’d convinced my university to pay for my airfare and the reserve to give me access, so I went. The reserve’s management had gotten it into their heads that my film department’s end-of-semester screening would be a useful marketing opportunity. They sent me on daily game drives, where white rangers, with the help of Shangaan trackers, zipped us around to the locations where we could observe and photograph the Big Five: lion, elephant, leopard, rhinoceros, buffalo. The reserve wanted me to film the animals, the charming guides, the lush amenities; I had other ideas. I was a young-looking twenty-one-year-old with too many pounds of borrowed film equipment and politics I couldn’t fully articulate. Over the walkie talkie system, I could tell that the Shangaan adjective applied to “baby elephant” and “lion cub” was being used to refer to me: “baby filmmaker.” This was embarrassing, but it also meant I wasn’t seen as a threat.

When asked, I’d explain that my film’s focus was the relationship between the local community and the reserve. The management was only too happy to show off: they let me film the “community tour” in which they bussed their guests to a nearby village to see the locals sing, dance, and throw the bones. Each tour included a visit to the elementary school, where students were pulled out of class to perform “If You’re Happy and You Know It” and hug their visitors.

The management was especially eager for me to film their anti-poaching efforts. As they saw it, they were engaged in a war against rhino poachers—local villagers recruited to sneak into the reserve and kill rhinos for their horns, which were sent to East Asia and sold on the black market. The management invited me along to the local middle school, where they held a presentation in which they tried blackmailing the students; there would be “no jobs and no money” if the children failed to inform on the poachers, they claimed. In the car ride back to the reserve, the presenters congratulated one another on what they saw as the important public service they had performed. So entrenched was their notion of poaching as an absolute evil, it did not occur to them that I might see things differently.

The students, in fact, were the children and grandchildren of people who had been dispossessed as recently as the 1970s, when the last of the reserve’s inhabitants were forcibly removed to create marketable “wilderness.” Relocated to new, ugly villages on the periphery, the Shangaan community was now impoverished, dependent on luxury resorts for employment as cooks, maids, and game trackers. Joe, the only Black ranger on the reserve, told me he could still remember watching his father, a cattle farmer, hunt a giraffe with a spear. He remembered, too, the bloody relocation, which resulted in decades of poverty.

The story is the same everywhere: A population lives alongside plants and animals within an expanse of land, hunting and farming sustainably. Colonizers move in, prizing the land for its “megafauna”—large, charismatic species like elephants, rhinos, and tigers. Trophy hunts ensue. Over time, maybe especially as the megafauna face extinction, the former colonizers (now only economically in control) pick up a conservationist vocabulary.

At this point, wilderness advocates flip the logic of the trophy hunt, swapping out rifles for cameras and criminalizing poaching. The population, meanwhile, is expelled and rendered reliant on an increasingly systematized tourism industry. The international wilderness movement has created millions of what Mark Dowie calls “conservation refugees.” As indigenous delegates said at the Fifth World Parks Congress in 2003, “First we were dispossessed in the name of kings and emperors, later in the name of state development, and now in the name of conservation.”

In 2003, eight thousand tribal people and low-caste farmers in the Indian state Madhya Pradesh were uprooted for the construction of a home for six imported lions. Two years later, the organization Project Tiger evicted several other communities to build new sanctuaries around the country. Despite its international acclaim, the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha wrote in the 1990s, Project Tiger “sharply posits the interests of the tiger against those of poor peasants living in and around the reserve.” That injustice, for Guha, is inherent to the wilderness movement, which around the world manages “a direct transfer of resources from the poor to the rich.” Wilderness conservationists do not aim to revise extractivist practices or reimagine a post-industrial relationship to land. Instead, Guha shows, they select picturesque vacation spots to serve as “a temporary antidote to modern civilization.”

The national park is a 19th century invention—a reaction to rapid industrialization. John Muir, founder of the wilderness movement and the Sierra Club, saw nature as a necessary foil to modern urban life. He instructed his followers to “break clear away, once in a while, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean.” On his first visit to California in 1868, Muir wrote that the indigenous people he encountered were, by contrast, “unclean” and had “no place in the landscape.” In his campaign to designate Yosemite a national park, Muir aimed to preserve the area for future tourists, not for the inhabitants who already lived there. In the early years of the park’s formal existence, Miwok Indians were put on display in public performances of traditional practices like basket weaving and acorn grinding. From 1916 to 1924, Yosemite even held an “Indian field day” for tourists. Later, when residence in the park was ruled contingent on employment, the Miwok became dependent on the Park Service for jobs.

Indigenous relocations had yet to trouble the national conscience. In the 1930s, the Works Project Administration put out a series of moralistic education films, including one about sustainable farming. The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) explains that though “The Great Plains seemed inexhaustible,” over-plowing had led to the Dust Bowl. The film’s privileging of land over indigenous people is hardly subtle: “By 1880 we had cleared the Indian, and with him, the buffalo, from the Great Plains, and established the last frontier,” the narrator intones. “A half million square miles of natural range.”

Sometime between the New Deal and the Great Society, liberals softened their rhetoric, but their politics of dispossession remained largely unchanged. The 1964 Wilderness Act defined “wilderness” as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” By 1969, the last settlement in Yosemite had been evacuated and razed. Even before then, most of the major parks (Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Mesa Verde, Mount Rainier, Zion, Glacier, Everglades, Olympic) had already been cleared of their indigenous populations.

“Wilderness,” even by the legal definition, is a chimera: the fiction that nature could exist outside history, that human impact on the animal and plant world could be contained or undone. Yet “wilderness,” an American export, soon caught on around the world—first in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, and then in the African colonies. In 1925, Albert Park was founded in the Belgian Congo as a reserve for both wildlife and pygmy hunter-gatherers. Between the late-thirties and the mid-fifties, the park’s eighty-five thousand inhabitants were evicted, prosecuted as poachers when they dared to return. In South Africa, Paul Kruger resolved to fence in an expanse “where nature could remain unspoilt as the Creator made it.” Today, Kruger National Park is headquartered in a place called Skukuza, named after a Shangaan moniker given to the warden of the first nature reserve in the area. “Skukuza” is a verb that means “to sweep away”—a reference to the forced relocation of the Shangaan.

In Tanzania, meanwhile, the Serengeti was first placed under protection by the British colonial administration in 1921 in response to a shortage of lions due to trophy hunting. An official national park was only established in 1951, under pressure from the Fauna Preservation Society (nicknamed the “Penitent Butcher’s Society”). By 1959, the Maasai people were evacuated from the park, and it became a world-famous safari destination—a development thanks, in no small part, to the intervention of a documentary filmmaker.

A former veterinarian in the Wehrmacht and director of the Frankfurt Zoological Gardens, Bernhard Grzimek turned to filmmaking relatively late in life when he assisted Leni Riefenstahl with the animal scenes in Tiefland (Lowlands, 1954). The two had been introduced in 1940 and became close friends.

Riefenstahl was the doyenne of Nazi cinema and a romantic—mountain metaphors feature heavily in her work. Film scholars have speculated that she was influenced by Man of Aran, which screened at the 1934 Venice Film Festival and won the Mussolini Cup, the top prize for a foreign film. (Riefenstahl would go on to win the same award in 1948.) Grzimek, in turn, borrowed heavily from Riefenstahl, copying motifs shot-for-shot from her propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935) in the nature documentaries he made two decades later.

In 1954, Grzimek and his son Michael traveled to the Belgian Congo to shoot No Room for Wild Animals (Keine Platz fur Tiere), which was intended to alert viewers to the problems of overpopulation, deforestation, and hunting. The film won two Golden Bears at the 1956 Berlinale, after which the British Government invited Grzimek to make a version about the Serengeti. The result was Serengeti darf nicht sterben (Serengeti Shall Not Die), which took home the Oscar in 1960.

In her later years, Riefenstahl followed Grzimek to Africa, where she shot the photography collection The Last of the Nuba (1973). She had been inspired, she claimed, by Green Hills of Africa, Ernest Hemingway’s account of a safari in which he kills a rhino. Susan Sontag reviewed The Last of the Nuba in a piece called “Fascinating Fascism” for the New York Review of Books. The collection, she wrote, “is about a primitivist ideal: a portrait of people subsisting untouched by ‘civilization,’ in a pure harmony with their environment.” While most viewers, Sontag thought, would interpret Riefenstahl’s photos as just “one more lament for vanishing primitives,” in fact they were “continuous with her Nazi work.”

It should not have come as a surprise that “blood and soil” fascism entailed a commitment to preserving the soil. The Third Reich was the first government to pass a law protecting the environment, and Hitler intended to ban slaughterhouses after the war. Not only was Riefenstahl’s romantic view of nature and of “primitives” consistent with Nazi ideology, Grzimek’s conservationism was less a departure from his wartime past than his allies in the wilderness movement might have liked to admit.

Grzimek espoused, to put it mildly, less than humanitarian views of the relative worth of animals and indigenous people. “A National Park,” he wrote, “must remain a primordial wilderness to be effective. No men, not even native ones, should live inside its borders.” In the film and the accompanying book version of Serengeti Shall Not Die, Grzimek casts the presence of Maasai cattle farmers in the region as a menace to its wild animals. He made no bones about what he wanted (and what, indeed, transpired): mass eviction.

Often credited with popularizing African wilderness conservation in the American collective consciousness, Grzimek is also cited as one of the founders of modern nature tourism. On his television show, Ein Platz fur Tiere (A Place for the Animals), he essentially bluffed the photo safari into existence, at least among a German audience. The show was a prime venue for proselytizing—in a typical scene, Grzimek addresses the camera from behind a desk on which a cheetah is stretched out, devouring raw meat—and Grzimek knew how to manipulate his fans. Concerned that newly decolonized African nations were insufficiently committed to animal conservation, Grzimek thought an influx of money from tourists might provide the right incentive. He directed his thirty-five million viewers to book cheap three-week safaris where they could photograph the animals he featured on the show. No such package deal was yet on offer, which was the idea: Grzimek’s fanbase called up all the German travel agencies, which rushed to meet the demand.

In the years since, the safari has grown more and more deeply entrenched in the economies of African nations, much along the lines Grzimek intended. So accepted has Grzimek’s logic become that a relatively new documentary could uncritically reproduce it and be met with critical acclaim. Virunga (2014) stars a team of (exclusively black) rangers, led by the (white, PhD’ed) Park Director Emmanuel de Merode in Virunga National Park. Together, the dedicated team fights to protect a small group of lovingly-shot gorillas under attack from poachers, local militias, and a British company aiming to drill for oil in the park.

“It is thanks to the animals, especially these gorillas, that our forest continues to be protected,” a ranger explains in a talking-head interview. “Tourism brings in money to help us sustain the conservation of nature.” Another adds, “Virunga National Park is really important because it contributes to the development of our country.” The justice of this arrangement, whereby human wellbeing is made contingent on the preservation of novelty animals that can attract tourists, is unquestioned: the gorillas’ continued existence is posited as a de facto good. The sacrifice of the one hundred and thirty rangers who have died defending Virunga is likewise portrayed as both worthy and worthwhile.

As several villains (both white contractors of the oil company and Black militia members) point out, de Merode is a member of the Belgian royal family. The accusation is cast as an attempt to undermine conservation efforts, but it’s telling. What the film does not reveal is that “Virunga” is only a less colonial-sounding title for Albert Park—named after King Albert of Belgium and cleared of its indigenous inhabitants. The colonial reasoning that threads just beneath the surface of the film did not appear to disturb conservationists or the popular press: Virunga was released to universal praise.

Today, Virunga National Park is in jeopardy. In April, twelve more rangers were murdered in an ambush by a rebel group. The park has lost so much tourism revenue due to Covid-19 that Virunga producer Leonardo DiCaprio has publicly pledged two million dollars to keep it afloat. Beyond Virunga, far from providing a reprieve from human interference, Covid-19 further endangers wild animals: due to park closures worldwide, poaching is on the rise. Rhino horns, meanwhile, have been marketed in China and Laos as a coronavirus cure.

Earlier this month, the Sierra Club published a notice about the impact of park closures on wild animals: “The Demise of Safari Travel Could Hammer African Conservation.” Readers, the piece begins, will understand how crucial it is to protect the animals from the economic repercussions of Covid-19 “If you’ve ever watched a wildlife documentary.”

“Nature is healing. We are the virus.” The Twitter thread went, appropriately, viral in mid-March, just three days before Tiger King premiered. In my first week of social distancing, I started seeing news of the supposedly drunk elephants in Hubei province and the dolphins in Venice—posted by the most reliable purveyors of fake news on my various timelines.

These clumsy efforts were soon supplanted by real news: coyotes in San Francisco, goats in Wales, wild boar in Barcelona. One op-ed asked us, on the basis of these anecdotal animal incursions, to “rethink our relationship to wildness.” Another reflected that, traveling to Yosemite during the pandemic, you might think you were “transported… to a previous era, before millions of people started motoring into the valley every year, or to a possible future one, where the artifacts of civilization remain, with fewer humans in the mix.” There was a pervasive sense that the pandemic was allowing us to see what the world would be like without humans, as if we could ever erase our geological and environmental mark.

In the meantime, “Nature is healing” became a meme. It was ironically applied to everything from a classic Windows desktop background to a still of Joe Exotic being attacked by a tiger. The original tweets were subject to heady analysis, labelled “ecofascism”—the ideology that human life ought to be sacrificed, via authoritarian measures, for the holistic good of “nature.” Historically, ecofascism emerged from Nazism, and has since been associated with the Unabomber and the El Paso shooter. “The positive ideal that we propose is Nature,” the Unabomber wrote in his manifesto. “That is, WILD nature: those aspects of the functioning of the Earth and its living things that are independent of human management and free of human interference and control.”

This part of the manifesto, at least, is not so far removed from the delusions voiced by Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man (2005), one of several recent documentaries that explicitly thematize a revenge of the natural world. Chronicling his life on videotape, Treadwell moved to Alaska’s Katmai National Park to live among bears. After he was—inevitably—eaten, his footage made its way to Werner Herzog, who edited it down and compiled it into a film. Treadwell, Herzog claims in his narration, is “fighting civilization itself. It is the same civilization that cast Thoreau out of Walden and sent John Muir into the wild.” But Treadwell’s Thoreauvian fantasy is deflated by Sven Haakanson Jr., the director of the nearby Alutiiq Museum. “If I look at it from my culture,” Haakanson tells Herzog in an interview, “Timothy Treadwell crossed a boundary that we have lived with for four thousand years.” Nature is violent, Herzog theorizes, and profoundly indifferent to human life. In the end, Grizzly Man posits an explicit moral: don’t assume nature to be a conservationist playground; leave wild animals alone.

It was equally difficult to miss the allegorical overtones in Leviathan (2014), Lucien Castaing-Talyor and Verena Paravel’s film documenting the drama of a commercial fishing vessel’s fight against rough waters. Blood laps up against the Go Pros they attach to various parts of the ship. We’re plunged violently underwater, seagulls cawing overhead. Leviathan, according to the New York Times, can “be read as an environmental parable in which the sea threatens to exact its revenge on humanity.” Or as James Franco put it in a baffling review in Vice: “This is life. Man versus nature. Man’s machines. Man’s mastery of the planet. Man’s ushering in of the apocalypse.”

Last year’s Honeyland is another self-conscious parable for ecological catastrophe. The film follows Macedonian beekeeper Hatidze, who cultivates her bees according to traditional, sustainable methods. But soon, nomads settle in and disrupt her delicate system, earning immediate profit but long-term calamity: all the bees, including Hatidze’s, die. “Hatidze’s story is a microcosm for a wider idea of how closely intertwined nature and humanity are,” Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov write in their director’s statement, “and how much we stand to lose if we ignore this fundamental connection.” Of course, to craft that microcosm, the directors could not strictly adhere to the facts. Hatidze’s story appears to take place over a single year, but it was constructed out of over four hundred hours of footage shot over three consecutive years. As Kotevska said in an interview, “In any reality, if you stay long enough, it becomes a great fiction.”

Ours is a culture that likes to fantasize about its own demise, and our cinematic output can serve as an index of contemporary anxieties. So pervasive is the notion that humanity has intruded too far into the wild that it’s easy, almost automatic, to read a revenge narrative into Covid-19. If the pandemic represents some kind of opportunity to reorient our thinking about nature and humans, civilization and the wild, we seem capable only of reinscribing the same old fatalistic mythologies. Inured to the fact that our impact on the planet cannot be sustained, we are content to contemplate our impending demise. It’s easier to entertain ourselves with eschatology than to dismantle the global system that animates it—the system that displaces entire peoples to monetize certain wild animals while displacing other wild animals in the demolition of the environment; the system that, when the immediate risk of the pandemic has subsided, will press onward to climate cataclysm.

Much the same way that fascist nature documentarians reproduced a politics in their own image, Tiger King’s tabloid intervention is suited to our age of distraction. Asked to pardon Joe Exotic for the attempted murder of Carole Baskin, Trump has said he’ll consider it—all but erasing the supposed issue (the welfare of wild animals) in service of sustaining the drama. Wilderness has always been a nonsensical idea, its conservation frequently a cynical project—and in Tiger King, that project finds an equally cynical vessel. Besides, it turns out the #1 threat to tigers is not roadside zoos: it’s deforestation.

Rebecca Panovka is an editor at The Drift.