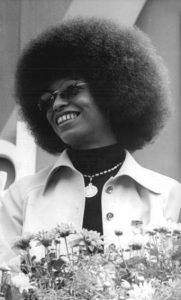

Courtesy of Yana Skorobogatov, with permission from Stanford University's Green Library (National United Committee to Free Angela Davis collection)

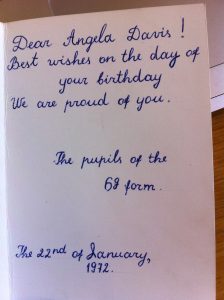

Courtesy of Yana Skorobogatov, with permission from Stanford University's Green Library (National United Committee to Free Angela Davis collection)

Several years ago, I found myself sitting at a desk in the main reading room of Stanford University’s Hoover Library. The box in front of me contained thousands of unopened letters, their thin red, white, and blue envelopes stacked indiscriminately. All were postmarked in the winter of 1972, and written in languages of the former Soviet Union: Russian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian, Ukrainian, Kazakh. Most notably, all were addressed to Angela Davis.

The box was just one of 506 that had been languishing in storage since the full set was purchased by the library in 1974. The letters remained untouched and uncatalogued until I arrived and opened them, one by one, carefully but eagerly. After so many years, it felt only right for someone to read them.

Today, we know Davis as a political activist, a retired professor, a writer, and, at 76, a social justice elder. In March, she was named one of Time’s “100 Women of the Year.” Writing on the occasion of the award, Ibram X. Kendi referred to her as “a legend, as revered by my generation of millennials as she is her own.” Since the election of Donald Trump, a new cohort of activists have been introduced to Davis. She spoke at the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., declaring that “the next 1,459 days of the Trump administration will be 1,459 days of resistance.” And in the wake of mass protests against police brutality, many have rediscovered her book Are Prisons Obsolete?, a classic abolitionist text published in 2003, long before the idea of prison abolition had made its way to cable news and Instagram feeds.

But in the winter of 1972, Angela Davis was not yet the “legend” that she is today. Aside from her doctoral dissertation on violence in German Idealist thought, produced under the supervision of the Frankfurt School’s Herbert Marcuse, Davis had not written much. She was also unemployed. In 1969, she had been dismissed from her first academic job, a two-year post in the Department of Philosophy at UCLA. Ronald Reagan, then governor of California, had ordered the state’s Board of Regents to fire Davis, citing public comments in which she had referred to police as “pigs.” Davis and her defenders framed the decision as a combination of racism and poorly disguised red-baiting, pointing to a 1949 policy banning the University of California from employing members of the Communist Party.

The scandal morphed into a fierce debate over the merits and limits of academic freedom: can a public institution of higher learning discriminate against employees on the basis of their politics? The New York Times, The Detroit Free Press, and other national outlets reported on the controversy, but no major newspaper came to Davis’s defense. Those journalists who did explicitly criticize Reagan and the Regents did so not to support Davis, but to lament the radicalizing effect her dismissal might have. A Los Angeles Times op-ed warned that any media attention could become “a rallying cry for extremists who would continue to destroy higher education.”

But the media and the public wouldn’t remain ambivalent about Davis for long. In the summer of 1970, the State of California charged her with kidnapping and murder after a gun used in an armed courtroom shootout was found to have been purchased and registered under her name. Davis fled the state shortly thereafter, launching a nationwide manhunt that would last for two months and earn her a spot on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list. In October, she was apprehended at a Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge in New York City and sent to the New York Women’s Detention Center to await trial.

Almost instantly, Davis became an internationally recognized cause célèbre. Protests bloomed in Paris, New York, Mogadishu, and Hamburg, each accompanied by posters and chants demanding that the American authorities “Free Angela Davis!” Her portrait became a fixture on buttons, t-shirts, and other memorabilia worn by the members of the post-Woodstock counterculture.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono released the song “Angela” to join the chorus of Davis supporters : “They gave you sunshine/ They gave you sea/ They gave you everything but the jailhouse key/ They gave you coffee/ They gave you tea/ They gave you everything but equality.” But the duo was quickly outmatched by the Rolling Stones’s own take on the genre. In “Sweet Black Angel,” an Afro-Caribbean inspired song released in April of 1972, the British rock band dispensed with teatime niceties: “She’s a sweet black angel/ Not a gun toting teacher/ Not a Red lovin’ school mom,” they sang. “Ain’t someone gonna free her/ Free de sweet black slave.”

“Free Angela Davis” defense funds emerged around the world, from Tanzania to Guyana, India to Egypt. They collected letters of support, financial donations, and legal advice. One such fund, the Palo Alto-based “Committee to Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners” received hundreds of thousands of letters between 1970 and 1974. Some came from the United States, but the vast majority were from the Soviet bloc. The committee’s offices quickly began to overflow, leaving its founder, civil rights activist Bettina Aptheker, eager to pass the letters on to Stanford, where I first encountered them.

No country was more vocally supportive of Davis than was the Soviet Union. Her name became so deeply embedded in official Soviet discourse that it even bled into diplomacy. In 1974, American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger expressed admiration for Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev’s willingness to tolerate a slew of sanctions that had been placed on the Soviet Union as punishment for its refusal to allow Jewish citizens to emigrate. “I would not put up with it if [Soviet Ambassador to the United States] Anatoly Dobrynin came in here and made demands about Angela Davis,” he said.

Davis’s appearance in the USSR coincided with a time of perceived ideological, spiritual, and economic decay. In 1972, Brezhnev was older than the Soviet Union itself, having just turned sixty-six. After decades defined by rapid economic growth, military victories, territorial expansion, and prestige projects like nuclear programs and space travel, Soviet society was settling into a period of stagnancy, a dangerous state for a country founded on the idea that “socialism is acceleration.”

Angela Davis was not the first martyr to emerge in the Soviet Union during a moment of crisis. Throughout its history, the Soviet state manufactured countless fictionalized socialist icons — from courageous war heroes to tireless industrial workers to assassinated party members to children who chose the Communist Party over their own families — to both inspire and distract its citizens. Angela Davis was only the latest to join the ranks of fallen heroes like Vasily Chapaev, Pavlik Morozov, and Aleksei Stakhanov, names and faces with whom all Soviet citizens were intimately familiar. The only difference was that she was alive.

Davis’s arrest and imprisonment provided the Soviet government with an irresistible propaganda opportunity. A persecuted communist? Check. Racial discrimination? Check. The silencing of an educated, seemingly liberated woman? Check. As the world’s first socialist state, one that claimed to have achieved economic, gender, racial, and ethnic equality, the Soviet Union was more than prepared to claim Davis as its own. And for a few months in the winter of 1972, it did just that.

In late 1971, Soviet bureaucrats organized a letter-writing campaign. Part classroom activity, part ideological indoctrination tool, the project encouraged schoolchildren to write letters to Davis on the occasion of her twenty-eighth birthday (January 26) and the International Day of the Woman (March 8). If the children could be mobilized to try to save a fellow communist living on the other side of the world, then perhaps their enthusiasm for the Soviet state could be rekindled. The goal of the “Free Angela Davis” campaign was never to free Angela Davis, but to save Soviet socialism.

Children from Riga and Kiev to Vladivostok took up pencils, pens, markers and crayons to write letters, postcards, petitions, and birthday cards to Davis. Whether in a school classroom, as a homework assignment, or as part of an activity at pioneer camp (the communist version of the Boy and Girl Scouts), they ultimately produced tens of thousands of letters, most of which ended up in Palo Alto, and, more than four decades later, in my lap.

Unintended time capsules, the letters were born in a time before a solid notion of Angela Davis had congealed in the public imagination. While the United States media was framing Davis as a revolutionary — someone who, according to scholar Lakesia Johnson, embodied the trinity of “Anger, Afro, Avenger” — the Soviet state forged an Angela Davis iconography of its own. It was an alchemy premised on the idea that people could (and maybe should) adopt the beliefs, aesthetics, and actions of extraordinary others as stand-ins for the beliefs, aesthetics, and actions of their ordinary selves. And for Soviet schoolchildren in the early 1970s, no one was more extraordinary than Angela Davis.

The Soviet Union had forged a strong pen-pal tradition as part of its educational and cultural programming. Writing to “friends” abroad, especially to fellow communists — within the Eastern Bloc and across the decolonized world, but also to interested interlocutors in the United States and Western Europe — had been in the Soviet Union’s soft diplomacy arsenal since the early years of the Cold War. What distinguished Davis from foreign pen pals before her was that she was not a willing participant; it was, in other words, a one-way dialogue, though the schoolchildren didn’t seem to notice.

Many addressed their letters to “our friend Angela” or “our dear friend,” asking Davis to write them back and including their home addresses. “Hello, kind friend! I wish you a happy birthday! Your friend, Virtiniya,” writes a student from Soviet Lithuania. From the Russian far north, another asks Davis to “write me at home, I would like to be friends with you!” A small Russian rhyme appears on one envelope: “fly with a ‘hi,’ return with a reply.” In a co-written letter, two secondary school students announce that they are “very good friends and want to become friends with you, too.”

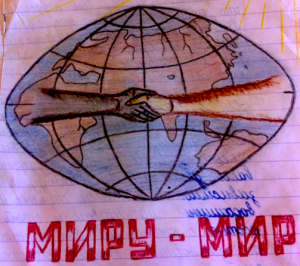

Hand-drawn images of Soviet scientific accomplishments, socialist iconography, and national emblems accompanied many of the letters. A young boy from Khabarovsk decorated his envelope with stars, hammers and sickles, airplanes, a Soviet naval flag, a generic red flag, and his own version of the Star of David, all rendered in variations of blue, green, and red ink. In addition to paintings, cartoons, and doodles, some envelopes included actual gifts: I found homespun political paraphernalia, red pioneer flags, and even a box of chocolates.

Other children took the letter-writing campaign as an opportunity to talk about themselves, their friends, and where they lived — a mode of introspection that was also part of a longer Soviet tradition of life writing. Under Stalin, the state explicitly encouraged its citizens to keep diaries and author memoirs and autobiographies to document their transformations into what the historian Stephen Kotkin termed “new Soviet men and women.”

The letters to Davis seem to have served a similar function. “Here is our beautiful Baikal!” reads a note on the reverse side of a postcard with an image of the lake on a warm summer day. The greeting comes from a group of preschool students in the city of Sliudianka on Lake Baikal’s southern shore. Another postcard, from a young boy writing from an industrial town in Soviet Lithuania, paints a much colder and more industrial scene. Its writer confesses to having read in a recent issue of Lithuanian Pioneer that Davis was lonely. He seems to sympathize: “It is winter here and it snows a lot. The weather is cold and we go to school.” His postcard depicts a factory and an adjacent parking lot, which he captions “our city.”

Since its founding in 1917, the Soviet Union had touted a commitment to ending all forms of oppression, including racism, which was portrayed in schools as an ugly byproduct of capitalist exploitation. Remove capitalism, the theory went, and racism would disappear, because all social conflict stemmed from economic inequality. Only a socialist economy could integrate all people through guaranteed employment and welfare.

The Soviet state had, since the 1920s, invited people of African descent as visitors to see firsthand what life under socialism was like. Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, and Claude McKay were some of the most illustrious of the many Black cultural figures to visit the country in the 1920s and 1930s and return home with broad praise for a welcoming, open-minded society. Less-famous visitors reported more awkward, even violent experiences: long stares, invasive questions, and, occasionally, physical and verbal abuse. But Black people continued to visit and even immigrate, especially during the age of decolonization, when the government courted men and women from newly-independent socialist African countries with offers of jobs and education.

The schoolchildren’s letters offer insight into the way that Soviet ideas about race in America were received by its youngest generation. Across the board, the children evinced the belief that Davis was a political prisoner, jailed for her participation in the Black freedom struggle. A group of primary school students writes, “We want for you to again fight for the rights of black people, so that people in your country could live the same way we do, like all of the Soviet people live.”

One letter signed by a class of young pioneers from the eastern city of Khabarovsk pledges to follow “your selfless struggle for the civil rights of your people,” and promises that their group will continue to remain with her in spirit. Yet another pioneer brigade, this one from a town in Soviet Kyrgyzstan, tells Davis, “we Soviet students are proud of your struggle for civil rights, of your resilience, and are certain that victory will come for your people.” Tamara Samorai, a third-grader from Soviet Kazakhstan, wishes Davis “good health and certainty in your struggle for the good cause, a cause for all the oppressed people.” Cheering her on from afar, the children offered the Soviet Union as a model for the kind of society that could one day exist in the United States.

In 1972, after more than two decades as diplomatic rivals, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to pursue a period of détente. Nuclear non-proliferation, cultural and economic exchange, and the sharing of scientific and technical expertise were just some of the policies initiated in this period. Calls for world peace — especially in Southeast Asia, where the Vietnam War raged on — and a world free of nuclear weapons became common tropes in Soviet propaganda. Brezhnev, himself a veteran of World War II, which claimed upwards of 26 million Soviet lives, ruminated excessively on peace in his own private diary.

It is not a surprise, then, that words like “peace,” “equality,” “happiness,” and “freedom” appear regularly in the children’s letters; they are words that the children would have seen emblazoned on all kinds of state-produced posters, public art and iconography. “We support you in your fight for freedom, happiness, and peace on the planet!” writes a third grader from Soviet Ukraine. A letter from students in the Moscow provinces recognizes Davis’s “struggle” as one dedicated to “strengthening peace all over the world.” A drawing made by a group of primary school students from Moscow speaks directly to the “peace” motif. It depicts two hands, one light skinned, the other dark, clasped together against the background of a planet, with “peace to the world” printed in block letters below — a strange mirror of a now-ubiquitous stock image, in 2020.

In March 1972, the journalist Hendrik Smith noticed a peculiar trend while traveling in Siberia, not far from the Mongolian border, on assignment for The New York Times: everyone was talking about Angela Davis. Dazzled by the sight of an American traveling in this remote region behind the Iron Curtain, one “young professional woman” took the opportunity to ask why “Miss Davis was being so persecuted.” Many in her town, she recounted, had been “so stirred by the Angela Davis case,” they had begun naming their children after her.

Fast-forward nearly half a century, and Davis has been claimed by people and institutions even more surprising than mothers in far-eastern Siberia. Part of her wide appeal has to do with the smorgasbord of political issues to which she has lent her name. Long before “intersectionality” became a buzzword, Davis used her public platform, her teaching, and books like Women, Race and Class to speak about the ties that knit together issues of race, class, gender, and war.

Perhaps most unexpected are the ways in which Davis’s brand is invoked selectively by those who prefer to ignore or whitewash her more radical positions. In the past four years alone, she’s been covered in Vogue, Elle, O!, Town and Country, and The Wall Street Journal, publications whose target audiences would likely be unsettled by her erstwhile popularity in the Soviet Union. Just this week, T Magazine, a fashion, beauty, holiday, travel, and design vertical published by the New York Times, selected Angela Davis as one of the faces of its annual “Greats” series, crediting Davis for the “current moment in grass-roots activism [as] one she both precipitated and inspired.”

Davis, who identifies as a Democratic Socialist, lent her support to Bernie Sanders in the 2020 Democratic Primary before offering a tepid endorsement of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. The party’s moderate wing — much of which dismissed movements for prison and police abolition — leapt at the opportunity to use Davis as another cudgel against those on the left who were less enthusiastic about Biden’s candidacy.

Revisiting the children’s letters, and parsing the inherited ideologies they reflect, is instructive in a moment when everything from PR emails to Instagram captions are laden with anti-racist rhetoric, and civil rights icons like Davis have come back into the spotlight. Forced into the public imagination for decades, the idea of Angela Davis at times seems almost completely detached from the actual person. Today, her brand is marshaled in ways that find a surprising echo in the phrases dutifully copied by 1970s schoolchildren in the Soviet Union, emptied of real actions or commitments past and present. Maybe the children’s view of Angela turned out to be right. She looms large; offering an expansive range of positions to seize upon. We look to her for moral guidance when we are lost, for consoling words in moments of crisis. To so many, she has begun to seem like a friend.

Yana Skorobogatov is an Assistant Professor of Russian and Soviet History at Williams College.