Illustration by Emma Kumer

Illustration by Emma Kumer

“Harriet Tubman was born a slave, and her story could have ended there. Instead, she persisted, escaping from slavery and becoming the most famous ‘conductor’ on the Underground Railroad,” begins the first section of Chelsea Clinton’s baffling 2017 children’s book, She Persisted: 13 American Women Who Changed the World, illustrated by Alexandra Boiger. True to its subtitle, the book marches on through thirteen stories of women persisting. Helen Keller persisted, by learning to read and write. Nellie Bly, told by a male colleague that working women were a “monstrosity,” persisted to become a working woman anyway. Sally Ride persisted to overcome stereotypes about women in STEM to travel to space. Ruby Bridges persisted when she attended kindergarten despite threats on her life from segregationists. Oprah Winfrey persisted by rising from humble origins to media superstardom. In case you managed to miss the message, it appears in bold, colorful letters in every woman’s story: “She persisted.”

This phrase, if you have managed to attain blissful amnesia about the immediate aftermath of Trump’s election, is drawn from something Mitch McConnell said about Elizabeth Warren, after the Senate voted to stop her from speaking during Jeff Sessions’s confirmation hearings. “She was warned. She was given an explanation,” McConnell said. “Nevertheless, she persisted.” This became an immediate feminist rallying cry, and was printed on bags, posters, pins, and t-shirts. In 2018, it was adopted as the “theme” of Women’s History Month (which, you might argue, already has a theme). Clinton notes in the dedication that she was “inspired by Senator Elizabeth Warren,” though Warren is not one of the book’s thirteen women who persisted.

This contemporary quote is an ill-considered retroactive framing device for a book about thirteen American women who lived during different times and under wildly different circumstances. There is an obvious flattening that occurs here: Winfrey’s persistence looked nothing like Bridges’s, or for that matter, Bly’s. Clinton applies a one-size-fits-all pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps narrative to multiple women’s stories in a way that ranges from tedious to outrageous; to suggest that Harriet Tubman’s story “could have ended there” if not for her persistence is to imply that people who were enslaved had individual responsibility to free themselves. Through grit and determination, the book suggests, any woman can succeed at any set of challenges! (And, it is careful to imply in some stories, pull other women up with them.) Reading She Persisted, one might get the impression that the experience of American womanhood over the course of the last 200 years has resembled that of doing an obstacle course — and winning.

She Persisted, whose original list price was $17.99, has sold nearly 450,000 copies and spent 47 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Unsurprisingly, it spawned sequels. There is now She Persisted Around the World, featuring a grab-bag of international women that includes J.K. Rowling, Malala Yousafzai, and nineteenth-century New Zealand suffragist Kate Sheppard. There is also She Persisted in Sports, about American Olympians who “changed the game.” It has even become a kind of franchise: there’s a series of chapter book biographies written by other authors that are sold under the She Persisted heading. (Clinton writes the intros.)

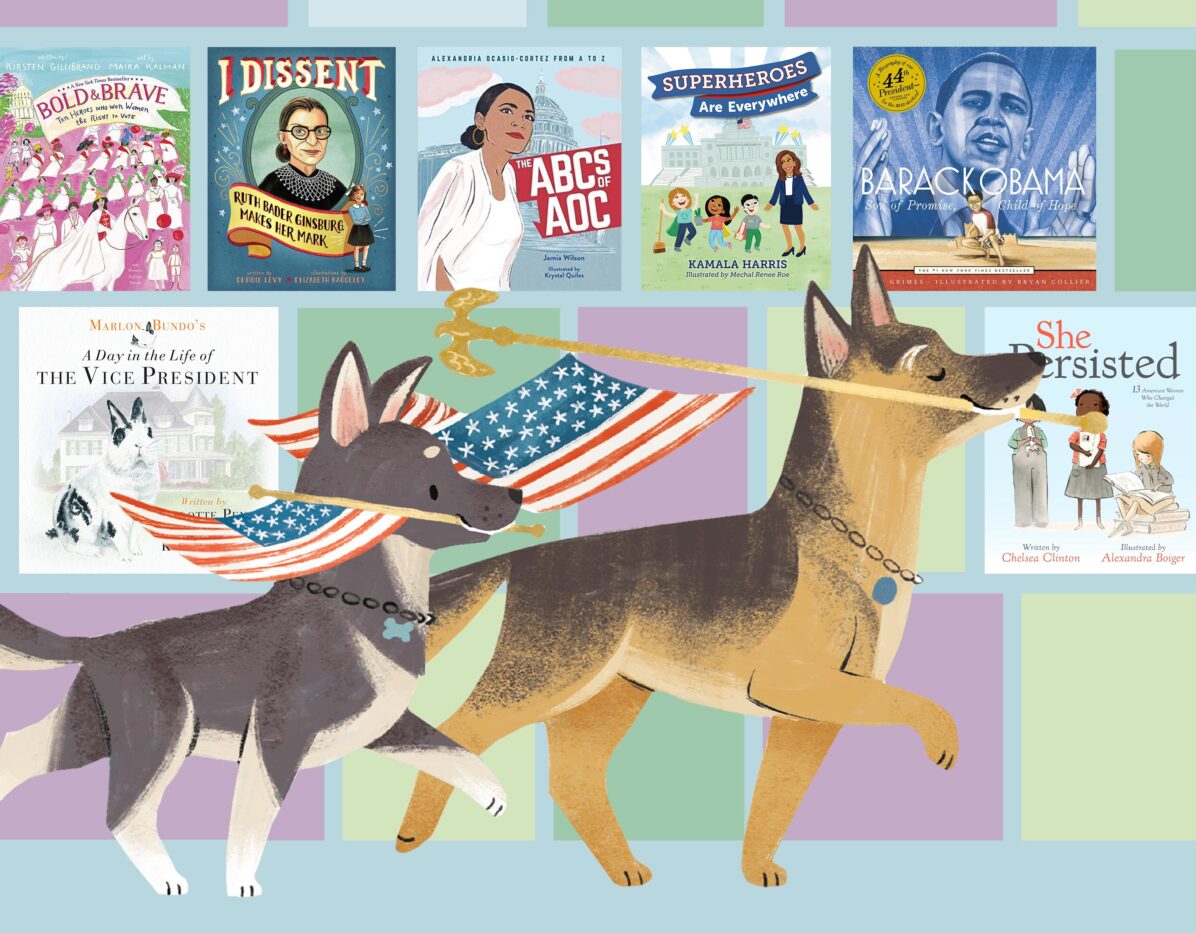

The project is a blockbuster in a genre that has become increasingly popular over the past decade: children’s books by political, or politics-adjacent, figures. Recent examples have been written by Kamala Harris, her niece Meena Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand, Charlotte and Karen Pence, Barack Obama, Condoleezza Rice, Sonia Sotomayor, Callista Gingrich, Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, Laura Bush, Jenna Bush Hager, and Barbara Pierce Bush. These join the realm of a related subset of picture books that are not by politicians themselves but that ride the coattails of political celebrity. The hagiographies include I Dissent: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Makes Her Mark; Mayor Pete: The Story of Pete Buttigieg; Revolution Road: A Bernie Bedtime Story; Little People, Big Dreams: Michelle Obama and Little People, Big Dreams: Kamala Harris; Joey: The Story of Joe Biden; Hillary Rodham Clinton: Some Girls are Born to Lead; Barack Obama: Son of Promise, Child of Hope; Journey to Freedom: Condoleezza Rice; Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice; Today’s Heroes: Colin Powell and Today’s Heroes: Ben Carson; My Dad: John McCain (by Meghan); The ABCs of AOC: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez from A to Z; a series comprised of Donald and the Fake News, Donald Builds the Wall! and Donald Drains the Swamp!; Elizabeth Warren: Nevertheless She Persisted; and, most recently, Dr. Fauci: How a Boy from Brooklyn Became America’s Doctor. Forthcoming this fall: Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi Calls the House to Order and Pinkie Promises by Elizabeth Warren.

These books are typically upbeat, didactic, and unimaginative. Many of them repackage the same themes and characters; frequently, authors select a set number of historical figures to celebrate. Obama picked thirteen American “heroes;” Chelsea Clinton picked thirteen American women; Gillibrand picked ten suffragists. They often rely on the repetition of certain catchphrases, so there is no way to miss the point, even when the point is remarkably banal. Yet they keep coming: in August, the imprint Philomel Books announced that it would be releasing ten more chapter books in the extended She Persisted universe, along with another picture book, She Persisted in Science: Brilliant Women Who Made a Difference.

One might feel compelled to ask why so many of these books exist, but the main reason is obvious: money. In 2003, Madonna published a picture book called The English Roses, a moralistic story about friendship and jealousy. Despite the fact that Madonna was not an obvious fit for a young audience, the book debuted at the top of the New York Times bestseller list and reportedly sold more than a million copies worldwide. It has been translated into 42 languages. Like She Persisted, English Roses led to spinoffs and a chapter book series. And it became a kind of test case, evidence that even an unexpected celebrity author could produce a bestselling book for kids. As in the grown-up books market, an established name — any kind of name — goes pretty far. Unlike your average children’s authors, celebrities can leverage massive social media followings and public relations networks to promote their books; they might even get booked on late night shows. Since Madonna’s hit, celebrities as disparate as Katie Couric and Pharrell Williams have authored kids’ books. (Perhaps it goes without saying, but many employ ghostwriters or co-authors.) With enough starpower, these authors can command big advances: Meghan Markle was rumored to have been paid £500,000 for a children’s book called The Bench that, in a rare turn of events, was panned by critics. Still, it hit the top of the New York Times bestseller list for picture books.

The economics of the whole endeavor are compelling: children’s picture books, which sell mostly in hardback, are not cheap. Kids are always growing into new sets of books, aging from young readers into young adult readers as their skills advance. In the mid-2010s, children’s books often appeared to buck broader publishing trends, continuing to grow as adult sales went flat. In 2020, driven by the pandemic and remote education, print sales of juvenile nonfiction jumped 23.1 percent — an anomaly, but representative of an overheated market nonetheless. Young adult fiction and nonfiction also saw major jumps, rising 21.4 percent and 38.3 percent respectively. In the past decade, amidst this flush market, some new marketing ploys emerged, including the growth of the “young reader’s edition.” These are books adapted from adult nonfiction, typically for kids aged ten and up — shorter, age-appropriate versions of popular books. They are often released simultaneously with expected blockbusters, or after-the-fact for bestsellers. Everything from Tim Tebow’s Through My Eyes to Michelle Obama’s Becoming has been released in this form. And why not? It only requires paring down existing content and repackaging it for a new audience. Crucially, too, it amps up the author’s advance but allows the cost to be shared between the adult and young adult divisions of the same publishing house.

Take Kamala Harris’s trifecta of books, published in 2019. Her kids’ book, Superheroes Are Everywhere, one of the more forgettable ones on the market, features a child version of Kamala, pointing out how everyone in her life was a hero who taught her lessons. It was released in tandem with her memoir, The Truths We Hold. According to Politico, Harris received a $446,875 advance for the memoir and $49,900 for a young readers’ edition of that same book, then an additional $60,000 for the children’s book. The editions for kids and teens had the effect of boosting Harris’s total advance above the half-million dollar mark. The bet on the children’s market paid off: the picture book’s sales surpassed hardcover sales of her memoir, which sold roughly 73,000 copies in hardback and 126,000 in paperback; Superheroes Are Everywhere has sold about 95,000 copies.

Book sales may be a drop in the bucket for some celebrities, but they can be major sources of income for politicians and ex-politicians. Books are like pieces of merchandise from which they can legally profit; writing books represents one of the few ways politicians can capitalize on their celebrity that is generally considered above-board, even by the most scrupulous. Defending his ascent into millionaire-dom, Bernie Sanders said, “I wrote a best-selling book. If you write a best-selling book, you can be a millionaire too.”

In addition to the cash-grab, there is a form of brand-building that occurs when a political figure publishes a book. This is true of most political memoirs, which tend to be career-boosting props rather than literary works. They are written for a fanbase, or a potential one, as an easy chance to tell one’s own story uninterrupted and connect it to one’s political platform. The branding involved in writing a kids’ book is related but slightly different — it’s not aimed at the readers themselves (non-voters, after all) but at the subset of people who may be buying books for them. Rather than laundering their personal anecdotes into potentially controversial policy proposals, politicians-turned-children’s-authors can lapse into easy platitudes that are virtually guaranteed to please. Family is good, as are women in general. There were many heroes in American history; there are many heroes in contemporary American life. Who wants to argue with that? Sometimes these books even creep into more traditional political posturing. Kirsten Gillibrand’s Bold & Brave: Ten Heroes Who Won Women the Right to Vote, another grab-bag of historical women, ends at the 2017 Women’s March. She includes a quote from her own speech.

Children’s reading material has long constituted a battleground in American culture wars, which have reached another fever pitch this year as conservatives work themselves up over the imagined demon of critical race theory in public schools. Curriculum bans are already being introduced in some states. Meanwhile, substantive critiques about representation and identity in young adult publishing have given way to a morass; authors are now regularly harassed online to the extent that their books are literally canceled before release. All of this is evidence of adults’ intense anxiety about how children’s politics will be shaped by what they read. A case in point: Dr. Seuss’s estate announced in March that it would not be printing six books anymore, due to the racist imagery they contained. The resulting conservative outcry — cancel culture! — meant that the sales of all six books skyrocketed, with resellers listing some of the discontinued titles for up to $500 on eBay. All of this was predictable and mind-boggling.

Children’s books written by politicians would seem to fit neatly into these battles, and in one sense they do; certainly, liberal customers are buying Harris’s books while only conservatives are shopping for Charlotte Pence’s. But in fact the political content of most of these books is murky. If they can be said to have any coherent politics at all, it is a politics of easy praise. Praise especially of determined individuals who succeed because they try really, really hard. There’s a sense in which this has been an eternal theme for children’s literature, which has always tended toward sanctimony and emphasized individuality. Even Aesop’s fables and Greek myths have morals. But at least interesting things happen in these harsh and occasionally brutal fictional worlds: Icarus flies too close to the sun and falls to his death; the industrious ant refuses to give the lazy grasshopper food as he starves; Medusa becomes so ugly that she turns people to stone. In stories that aren’t written with the trepidation of a person running for office, there is at least a possibility that characters might do something unexpected, or even bad.

The hagiographies of contemporary political figures are also heavily sanitized. There is little room for complexity in a picture book intended for readers aged four to eight about Dr. Fauci that crowns him “America’s Doctor” midway through a devastating pandemic. Nor is there in I Dissent, by Debbie Levy, which is committed to the extreme mode of infantilizing adulation that Ruth Bader Ginsburg inspired late in her life, such that she became as much a moniker (“RBG”) as a living and breathing woman. This is not to say that children shouldn’t read biographies, but merely that these books don’t need to be so relentlessly committed to spoon-feeding children laudatory stories about the people currently in power. In I Dissent, a few pages are devoted to the beauty of Ginsburg’s friendship with Antonin Scalia — a lesson, presumably, about bipartisanship, one that conveniently ignores the abhorrent substance of his views.

This across-the-aisles smarminess is not incidental. It’s a feature of the hollowness of these books’ politics, which become evident if you compare books written by liberals and conservatives. In 2003, then-second lady Lynne Cheney published A is for Abigail: An Almanac of Amazing American Women. The illustrations are zanier, and it’s more crammed with text, but it is an obvious forerunner to She Persisted, featuring a veritable cornucopia of American women from Abigail Adams to Zora Neale Hurston. (Cheney occasionally gets creative with the alphabetization, as in, “V is for Variety: who can count all the things girls can grow up to be?”) Once again: look at all these American women, kids!

One might do a side-by-side close reading of two recent additions to the canon: Marlon Bundo’s A Day in the Life of the Vice President, written by Charlotte Pence and illustrated by Karen Pence, and Champ and Major: First Dogs, by Joy McCullough. These books take advantage not only of the political celebrity of a person in the White House, but of the celebrity of White House animals. Presidential pets have long been objects of public fascination: indeed, in 1998, kids’ letters to the Clintons’ cat and dog were collected and published as their own book. Now, all the animals have Instagrams. In the Pences’ book, the family bunny, Marlon Bundo, gets a tour of Washington — rendered in verse. (Hilariously, in need of a rhyme with “me,” Pence has Marlon Bundo visit “the wonderful EEOB!”) Marlon Bundo gets tired, and at the end of his day he gets to say a final prayer and cuddle with Mike Pence, whom he calls Grandpa. In First Dogs, meanwhile, Joe Biden gets called Dad by his two German Shepherds, Champ and Major, who are depicted on the cover carrying American flags in their mouths. Champ is the older dog; he shows Major the ropes, especially how to stop their busy dad from working all the time. Then Joe gets a new job and they move to the White House, where Champ has already lived, so he can show Major around. At the end, they sleep peacefully while a smiling Joe talks on the phone in the Oval Office.

To encounter these books without any political context would be to read two boring books about animals navigating Washington D.C. But as always, context is everything. In fact, the politics are so entwined with the whole endeavor that Jill Twiss, a writer for Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, published another book about Marlon Bundo, in which the bunny realizes he is gay — an elaborate troll that became a number one New York Times bestseller, and whose funds went to The Trevor Project. (Of all these books, this one has the most dynamic and heartwarming plot.) Still, there is no escape from this war over symbols that has expanded to include fictional versions of presidential pets. Characters, themes, and tropes are repackaged and resold under the umbrella of different political brands.

Children’s book publishing, like the rest of book publishing, is obsessed with the present and the recent past. This is most evident in the market for adult nonfiction, which runs on the never-ending churn of political memoir, even in the post-Trump era. Dozens of books have already been written or sold about the Covid-19 pandemic, documenting last year for this year’s audience. Of course, some of these books age badly and quickly, as the fallout from Andrew Cuomo’s $4 million mid-pandemic book deal has shown.

Some of the recently published children’s books have also aged awkwardly. Toward the end of I Dissent, which was published in September 2016, Ginsburg’s refusal to retire is presented as another in a long line of her courageous refusals: “Some people have said [Justice Ginsburg] should quit because of her age. Justice Ginsburg begs to differ. She works as hard as ever. She exercises in the gym. She never misses a day in court.” The rest is history: Trump won. Ginsburg died last September, ensuring the appointment of a conservative judge to replace her; in hindsight, Ginsburg’s “begging to differ” was not an act of anti-ageist defiance but an exercise in ego that will have ramifications for generations. Even First Dogs, published at the beginning of 2021, has aged poorly. Rather than settling into the White House peacefully together, Major bit two staff members and had to be, at least temporarily, exiled to Delaware. A few months later, Champ died.

This is a much more interesting story to me, because it is both troubling and true — true in a factual sense but also true in the sense that it contains something meaningful and real. Imagine: a story about a dog who has trouble adjusting to his new home and acts out because he is afraid. Or the story of another dog, who after many happy years with the same family, dies peacefully and leaves a younger brother behind to grieve. The stories that moved and changed me when I was a young child were more like this: stories that were really about life, since life includes bad behavior and sorrow, as well as death.

When I was a kid, I insisted that my mother read me Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree over and over. Published in 1964, it’s a story about a boy who takes and takes from a tree over the course of his life until the boy is an old man and the tree is left a stump. “And the tree was happy,” the story ends. It’s a strange book, with an ending that is heartbreaking but also streaked with strange joy. I was surprised to discover recently that The Giving Tree is considered “one of the most divisive in the canon” of children’s literature in large part because its moral is unclear. Why is the tree happy when it has been sucked dry? Are we supposed to understand the relationship as one defined by generosity or abuse of power? There was even a 2014 article in The New York Times about whether The Giving Tree is a “tender story of unconditional love or a disturbing tale of selfishness.” Why not both, or, really, neither? It seems many of us can no longer imagine that children can handle, and may in fact prefer, stories defined by ambiguity — stories that have little to do with contemporary politics but rather to do with life as it is lived. The Giving Tree might be complicated, but it isn’t boring or pat. It isn’t pandering to anyone. At the very least, this was a story written with children in mind.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review. She is at work on a book about collections.