Diane Arbus, Triplets in their bedroom, N.J. 1963 © The Estate of Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus, Triplets in their bedroom, N.J. 1963 © The Estate of Diane Arbus

“I am not ghoulish, am I?” Diane Arbus wrote to a lover in 1960, describing how she couldn’t help but stop and watch as a woman lay crying in the street. “Is everyone ghoulish? It wouldn’t have been better to turn away, would it?”

For half a century, Arbus’s work has kept us asking these same questions. Her unlikely subjects have become almost proverbial: the twin girls, dressed in identical black dresses, looking creepily into the camera (purportedly the inspiration for the twins in The Shining); the Jewish giant looming over his little parents; the “female impersonators,” as Arbus sometimes called men in drag; the couples — straight, queer, interracial, old, ridiculously young; the mentally disabled women holding hands; and, perhaps most famous of all, the wigged-out kid clasping a toy hand grenade in Central Park. Arbus was attracted to people who were visibly different — to those she called “freaks.” You feel a “quality of legend” about them, she once said, “like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.” Outside narrow academic channels, those words have framed her reception ever since: Arbus is the one who took pictures of weirdos and grotesques, always cruising for difference. In turn, she, too, has acquired a “quality of legend.”

The origin of the Arbus myth can be traced with unusual precision to a landmark 1972 show at the Museum of Modern Art, which traveled to galleries across the world and finally elevated Arbus from working photographer, scrambling for commissions from magazines and newspapers, to capital-A artist and cultural icon. The show remains one of the most visited exhibitions in MoMA history, though Arbus herself never saw it: she died by suicide the year before it opened. Last year, to mark the 50th anniversary of Arbus’s posthumous breakthrough, David Zwirner rehung the 115 photographs from that original MoMA show in a new one called Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited. (The Drift receives funding from David Zwirner.) Cataclysm greeted visitors not with photographs, but with words — unattributed observations and judgments and praise scattered on the walls without the usual didactic logic of wall text. The symbolism was apt: to get to Arbus, you have to wade through a storm of opinions that has long warped our view of her work and rendered the critical debate less interesting than it should be.

Every Arbus show or publication has presented an opportunity to consider anew the Problem of Diane Arbus: what should we make of the freaks? Are the photographs cruel or compassionate? Demeaning or dignifying? Many critics have sought the answer in Arbus herself. One camp, represented most notoriously by Susan Sontag, has regarded Arbus as a daughter of privilege who sought out ugliness so that she could throw it in the face of the bougie gallery-going audience. The opposite camp has insisted that what seems like exploitation is actually empathy: by depicting what’s supposedly aberrant with a special fellow feeling for the marginalized, Arbus expands our notion of what’s normal. The seeds of this narrative were laid by John Szarkowski, MoMA’s longtime photography curator and Arbus’s most important champion, who, praising her “truly generous spirit,” wrote that her pictures “record the outward signs of inner mysteries” and “show that all of us — the most ordinary and the most exotic of us — are on closer scrutiny remarkable.”

This sentiment has proven remarkably durable: in a review of Cataclysm, Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post critic Sebastian Smee wrote that Arbus’s subjects “no longer look like ‘freaks.’ They look like what they are: fellow human beings.” The world has caught up to Arbus, Smee suggests. We’re finally prepared to appreciate her humanistic project for what it was. But this is Arbus defanged, banalized — Arbus as the forerunner of body positivity, of diversity, of love is love is love. Smee, like Szarkowski and many after him, centers the artist’s life story: “Arbus was a complicated person. Depressive, restless, and sexually adventurous, she craved intense experiences. But it was her complexity that allowed her to see and capture the complexity and unknowability of her subjects.” In this telling, Arbus’s biography, which testifies to her own “inner mysteries,” is used to help straighten out the problem of a privileged white woman on the prowl for weirdos — a woman who once compared taking pictures to being a butterfly collector, or Dick Tracy.

And yet it’s precisely the photographs’ resistance to resolution, their anti-essentialism about the people they show, that continues to act on us long after their shock value has waned. Now that we’ve grown used to the reflexive celebration of difference, and to prizing positionality as the key to understanding any artwork, Arbus’s pictures unsettle us with their refusal to yield answers to the kinds of quandaries that, in the five decades since she catapulted to fame, we’ve only grown more impatient to resolve. Are they ghoulish? Are we ghoulish? Would it be better to look away?

Arbus’s short life could be told as a riches-to-rags tale; an allegory for the cultural tumult of the sixties; or, even in sympathetic hands, yet another fable of the sexy suffering female artist. Born Diane Nemerov to a well-to-do merchant family in New York in 1923, she and her older brother (the celebrated poet Howard Nemerov) were educated at Fieldston, a progressive private school favored then as now by the bien pensant upper-middle classes. It was thought that she would become a painter, though her probing school essays and often poetic letters reveal that she was also a serious, opinionated student of literature. At only eighteen, in her first step down the social ladder, she married Allan Arbus, a City College boy who worked in her father’s department store. After the war, the couple made ads for the family business before opening a commercial photo studio together, which produced images for magazines like Glamour and, later, Vogue. Diane came up with the concepts for their shoots; Allan was the photographer.

Then one day in 1956, fed up with the fashion work, she quit the shared studio. She had been taking her own pictures for more than a decade already, but now she began studying with the Austrian émigré photographer Lisette Model and working in earnest. As she found her professional footing, she and Allan grew apart, eventually separating in 1959. (They would always remain touchingly entangled, not least because they had two daughters, and Allan supported Diane morally and materially for the next decade.) Meanwhile, Arbus shot celebrities for The New York Times Magazine and regularly contributed to Esquire, whose New Journalism aesthetic fit her own. Her editors there, and at Harper’s Bazaar, were receptive to her interest in subcultures, social interstices, and twilight zones — Arbus immediately gravitated toward Coney Island, the subway, Central Park, and the cinema, where she took striking stills of faces on the big screen. She shot Mr. Universe and Miss New York competitors, debutantes and Bowery bums, and other representatives of the kinds of small winners and losers that populate a city like New York. Her Esquire projects from this period already reflect what we now regard as her primary preoccupation: people who were interesting to stare at, engaged in private acts and public rituals of self-display and self-creation.

While Arbus was working for magazines, she also got to know MoMA’s John Szarkowski, leaving a portfolio for his review in 1962. The museum acquired seven of her pictures two years later. And, though Arbus initially felt it was too soon to exhibit her photographs, in 1967 Szarkowski included her in a MoMA show called New Documents alongside Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. The influential exhibition brought together what Szarkowski saw as an emerging generation of documentary photographers. Unlike those interested in bringing about political change (Lewis Hine, Jacob Riis) or in documenting and dignifying American folkways in order to shore up the mission of the New Deal (Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee), the New Documentarians’ aim, Szarkowski wrote, was “not to reform life but to know it.”

Arbus got her own room in the show, as well as most of the critical attention. Fascinated yet bewildered, reviewers didn’t seem to know what to make of her pictures. “Even her glamour shots,” noted the Times, “look bizarre.” In Arts Magazine, Marion Magid admired how Arbus satisfied a “craving to look at the forbidden things one has been told all one’s life not to stare at.” She described the show as “a kind of healing process,” in which viewers were “cured of our criminal urgency by having dared to look. The picture forgives us, as it were, for looking.” Arbus herself didn’t think her photographs were so pure. She later spoke of her photographic encounters as acts of persuasion, even cajolery. “I think I’m kind of two-faced,” she once said. “I’m very ingratiating. It really kind of annoys me. I am just sort of a little too nice. Everything is Oooo. I hear myself saying, ‘How terrific,’ and there’s this woman making a face.”

If Magid found healing in Arbus’s portraits, Arbus herself was increasingly unwell. A working single mother of two, her physical and mental health were becoming an issue. In 1968, exhausted and short of money despite the success of her MoMA debut, Arbus checked herself into a costly private hospital for a three-week stay. Doctors found that her liver had never fully recovered from the bout of hepatitis she’d had two years before, and was under added stress from birth-control medication and antidepressants. “When I was most sick and scared,” she wrote after coming home, “I was no longer a photographer (I still am not and something about realizing that I don’t Have to Photograph was terribly good for me).” That same year, Arbus took on teaching — which she despised — to make ends meet. She was working feverishly but also living ever more riskily, purportedly approaching strangers on the street and propositioning them for sex. All the while, she continued to write compulsively to her closest interlocutor and longtime lover Marvin Israel, the art director at Harper’s Bazaar for a time and a shitty media man avant la lettre; he had a strenuous affair not just with Arbus, but later, it was rumored, with her daughter Doon as well.

Despite the difficulty of this period, Arbus began work on a new set of pictures that she described as “FINALLY what I’ve been searching for.” Now known as the “Untitled” series, these images were shot at two New Jersey psychiatric hospitals, but beyond the walls of the institutions themselves — her subjects are seen outside in their Halloween costumes, or standing with friends on a playing field, or even at the swimming pool. Though some now count among Arbus’s most famous photographs, she never exhibited them; the New Documents show had been the first of her life, and it also turned out to be the last. In 1971, professionally ascendant but ever more unwell, Arbus killed herself in her West Village bathtub.

When, the following year, Szarkowski mounted the MoMA retrospective, Arbus herself was in some sense on display. In a Times review headlined “Her Portraits Are Self-Portraits,” the critic A.D. Coleman called Arbus’s work “the naked manifestation of the artist’s own moral code in action,” which “demanded her own self-revelation as the price for the self-revelation of her subject,” subtly implying that Arbus had paid the price for her art. Lines for the show went around the block; the accompanying monograph, which Aperture initially had to be persuaded to produce, sold out twice. (There are now more than half a million copies in print.) Once a well-regarded, if idiosyncratic, working photographer, Arbus was now world famous, and critics rushed to answer the riddle posed by what was now an oeuvre. In Time, Richard Hughes wrote that she “has had such an influence on other photographers that it is already hard to remember how original it was.” In Camera 35, the critic Lou Sterner disagreed: “Rarely have I read as much nonsense as the aura of almost patronizing worship covering the work of Diane Arbus at the Museum of Modern Art.”

It was this sacred aura that Susan Sontag — whom Arbus had photographed in 1965 — sought to dispel. In “Freak Show,” the 1973 essay in the New York Review of Books which would become the second chapter of On Photography, Sontag accused Arbus of engaging in one of “art photography’s most vigorous enterprises — concentrating on victims, on the unfortunate — but without the compassionate purpose that such a project is expected to serve.” Arbus showed “private rather than public pathology, secret lives rather than open ones,” Sontag wrote, finding fault with the “inner mysteries” that Szarkowski had praised. In her reading, Arbus was a spoiled brat from a “a verbally skilled, compulsively health-minded, indignation-prone, well-to-do Jewish family” using her camera as “a kind of passport that annihilates moral boundaries and social inhibitions, freeing the photographer from any responsibility toward the people photographed.” The whole project “was her way of saying fuck Vogue, fuck fashion, fuck what’s pretty.”

Many critics have since dismissed Sontag’s ethical conclusions (Peter Schjeldahl called the essay “an exercise in aesthetic insensibility”), but it’s hard to argue with her analysis of Arbus’s class position. As Arbus once blithely admitted, “One of the things I felt I suffered from as a kid was I never felt adversity.” The tragedy of her suicide seems to make it all the more tempting to put Arbus front and center — to frame her, as one scholar put it, as “Sylvia Plath with a camera.” The three English-language biographies have only shored up the mythology, even as they try to pick it apart. Patricia Bosworth’s gossipy 1984 volume, based on interviews with Arbus’s family and friends, is much less interested in photography than sex (“a pall of smut hangs over the book,” one critic wrote). William Todd Schultz’s cringeworthy 2011 psychobiography, An Emergency in Slow Motion, draws on new interviews with the psychiatrist who treated Arbus at the end of her life. Arthur Lubow’s definitive 800-page tome from 2016 is more measured, but still can’t resist alleging that Arbus was engaged in an incestuous relationship with her brother Howard until just weeks before her death. This almost comically scandalous claim is based solely on the testimony of Arbus’s psychiatrist, who hadn’t seemed so confident about that assertion when speaking to Schultz a few years earlier. Though the books get longer and longer, they primarily hash and rehash her various romantic entanglements, family dramas, and insecurities. Arbus’s actual work is too easily collapsed into pathology — “a symptom,” as Schultz writes, “of her psychological dislocation, her isolation, her alienation.”

This might explain why, for decades, the Arbus estate kept countless personal documents, as well as photographic negatives, locked away. Doon wrote that after 1972, the Arbus “phenomenon” started “endangering the pictures.” In 2003, the estate broke its silence, publishing a flood of excerpts from letters and diaries in a book titled simply Revelations. The aim wasn’t transparency so much as superfluity: “This surfeit of information and opinion,” Doon hoped, might “finally render the scrim of words invisible so that anyone encountering the photographs could meet them in the eloquence of their silence.” Even the estate seemed unable to deny the allure of the troubled female artist — the book reproduces Arbus’s autopsy report in full, including descriptions of the ligaments she cut when she ended her life and the weight of her heart (320 grams). As Janet Malcolm observed, Arbus emerges from Revelations “looking just as brooding and morbid and sexually perverse and absurd” as before.

No amount of biographical information seems capable of liberating Arbus from the critical groove in which she’s been stuck for five decades. The emphasis on psychology — the photographer’s, her subject’s, our own — has helped make these pictures famous (and surely boosted their value), but it’s also primed us to misread or even ignore what’s most powerful about them, which is how they thwart any access to internality, how their visual precision complicates moral clarity. In Arbus’s hands, photography refuses to do what biography most hopes to: to fix or capture a self. Instead, her genius is in deconstructing the illusion of identity, tripping us up in the rush to empathy. These pictures aren’t about “being seen” so much as being looked at, and looking.

Take Arbus’s famous “A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C., 1968.” In front of a cot strewn with laundry, a man stands in delicate contrapposto. His face is made up; his penis is tucked between his thighs. He looks straight at the camera, his exquisite poise at odds with the seediness of his surroundings. As Hilton Als noticed, the man looks curiously like Botticelli’s Venus; as Arthur Lubow pointed out, the curtains that frame him recall the baldacchino of Renaissance portraiture. My eye always gravitates towards the man’s feet — the contrast between the light step of his right foot, hovering with genuine grace, and the beer can next to them. The man is carefully organizing himself — as in many of Arbus’s portraits, there appears to be a mirror in the room — but he’s in the midst of a disturbingly disorganized mess. We’re witnessing a kind of performance, complete with curtains and makeup, but it’s impossible to say if it’s “a deeply private exchange with the self,” as Als has written of this picture, or a burlesque.

Equivocation between lofty allusions and gritty details, idealized dreams and stubborn realities, is everywhere in Arbus’s work. The subjects of “A husband and wife in the woods at a nudist camp, N.J. 1963,” who stand side by side beneath the trees, their imperfect, locker-room bodies on full display, are Arbus’s Adam and Eve. (In an unpublished text meant to accompany the pictures in Esquire, she described the camp as a dime-store Eden.) Her portrait of “Russian midget friends in a living room on 100th street” contains a mirror that evokes Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (not to mention the people with dwarfism), a painting that delights in the mechanics of visual representation. And the processions of mentally disabled people from the “Untitled” series, wearing masks and costumes on Halloween, recall Bruegel’s scenes of joyous peasant revelry. What should we make of the gap between these photographs’ refined composition, even artiness, and their earthy, unbeautified content? Does Arbus’s photograph of the man pretending to be a woman send him up, or support him? Or is the real joke on the viewer who insists on one interpretation or another?

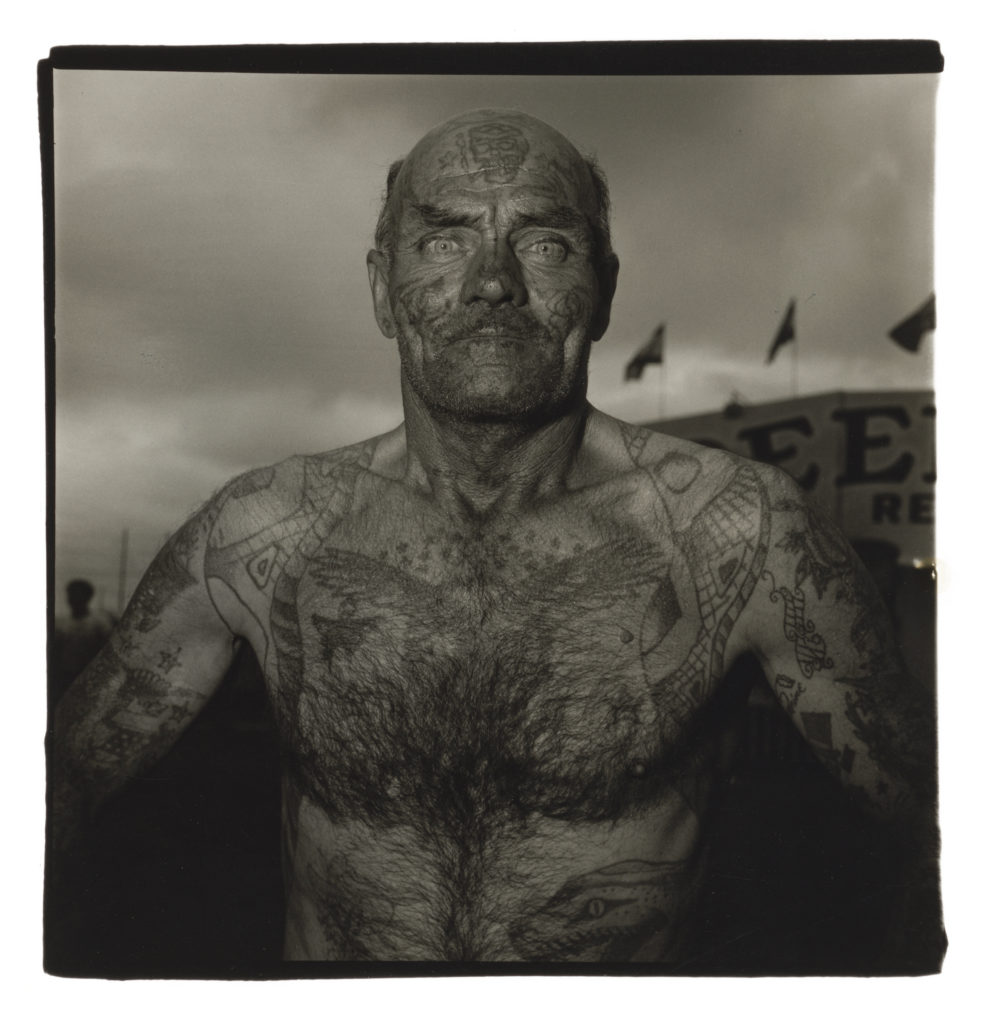

After 50 years of social change and ever-increasing visual inundation, no one will be surprised by “Tattooed man at a carnival, MD. 1970,” whose gray eyes look straight into the camera from beneath the cigarette-smoking skull inked on his forehead, or by the caked makeup and lazy eye of “Girl with a cigar in Washington Square Park, N.Y.C. 1965,” and certainly not by “Blonde female impersonator with a beauty mark in mirror, N.Y.C. 1958.” Today, you’re much more likely to wonder why Arbus insisted on the biological gender of her queer subjects, or to pause over the pictures of mentally disabled people from the “Untitled” series, who did not, and probably could not, consent. (She was able to gain access to one institution by calling in a favor from a friend in New Jersey politics.) What makes the pictures not just inscrutably beautiful but also subtly subversive is the indeterminacy intrinsic to the photographic medium, which Arbus intentionally brought to the fore.

Arbus was not the first to work at the social margins. Photographers, whose own status in the artistic hierarchy has often been marginal, have always gravitated toward the people and places that fine art traditionally excluded, from E.J. Bellocq’s portraits of sex workers in New Orleans to Walker Evans’s lovingly antiquarian pictures of painted billboards and James Van Der Zee’s pictures of black life in New York (to name three artists important for Arbus). And many photographers known for their glossy images also spent time in the shadows: Peter Hujar and Richard Avedon both shot pictures in mental institutions before Arbus did; a generation earlier, Brassaï took nostalgic photographs of tramps and prostitutes, eventually collected in The Secret Paris of the ’30s. Arbus’s own teacher, Lisette Model, famously made a portrait of a well-known “hermaphrodite” she called “Albert / Alberta,” among other characters. And of course there’s Weegee, whom Arbus helped rediscover, and whose strobe-lit car crashes and crime scenes turned ambulance-chasing into an art.

Arbus’s mature pictures, though, are more formal and controlled. Many of her earlier photographs had a snapshot quality — intentionally grainy or roughly cropped. But in the late fifties, around the time she started studying with Model, Arbus refined her techniques: she strove to make the clearest, crispest prints possible; she stopped cropping and began printing the borders of the negatives, as proof of both the photograph’s unedited integrity and its status as mere image. These practices, she said, have “to do with not evading the facts, not evading what it really looks like.” She called this “scrutiny.”

“What it really looks like,” though, wasn’t just a matter of chance — and Arbus knew it. Even her intimate pictures are never candids. She was interested in how people posed for her camera and for the world. “Everybody has this thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way and that’s what people observe,” she wrote:

You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw.… Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way, but there’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can’t help people knowing about you.

Arbus chased “the flaw” — what, at other times, she called the “anomaly” or “the Difference,” a feature that thwarts our effort to project a certain self to the world and reveals the shadow of something else. Arbus aptly described this as “the gap between intention and effect.” Advertising images — the kinds Arbus and her husband produced for Glamour and Vogue — seek to close that gap. In her art, Arbus made the gap her subject.

“Transvestite with a picture of Marilyn Monroe, N.Y.C. 1967” does this most explicitly, almost heavy-handedly. A slim, smiling person (Arbus would probably say “man”), naked except for his makeup and lacey black panties, holds up a framed portrait of the movie star next to his face. The real and the ideal are juxtaposed so baldly it’s ridiculous. But here, too, the gag could lampoon both subject and viewer: is he holding up Marilyn as aspirational (surely with a touch of irony), or as the standard against which he’s unfairly judged? The crossdresser will inevitably fail to be Marilyn, but at the same time we’ll inevitably fail to see him as anything but not-Marilyn. Both of us are blinkered by the ideal, Arbus suggests. Even in much more subtle pictures, she wants us to attend to the way a person or sometimes even an empty room tries to be something; the viewer, in perceiving that effort, always also sees its futility, too.

Photography, as Arbus well understood, is a good medium for such exposure: it shows us the stubble on a crossdresser’s face, or the tawdry gleam of a proud-looking young man’s polyester shirt, or the hoarder-level accumulation surrounding a New York society marm in her bedroom. A photograph, particularly one of Arbus’s tightly framed close-ups, inevitably records too much information, even more than the photographer knows she’s capturing at the time; there are details which won’t be revealed until the image has been developed, creating another “gap between intention and effect.” And while snapshots can eternalize the hidden elegance of a throwaway moment, when the camera is turned on someone who poses, striving for the simple legibility of an icon, it tends to make us hone in on the failure of composure — grace’s limits. What perfection or (in the case of Arbus’s identical twins and triplets) sameness there is in a photograph makes us attend all the more quickly to the flaws. “A photograph is a secret about a secret,” Arbus famously, and obscurely, said. “The more it tells you the less you know.”

The photos of mentally disabled people in “Untitled” insist that we accept what we don’t and can’t know; they’re among Arbus’s hardest riddles. Like her earliest work, they’re often taken on the fly. Their subjects, shown outdoors, rarely look straight at us. These are portraits of people who cannot fully compose or control themselves for the camera; their mental differences place them beyond the usual game of self-presentation and self-transformation that so many of Arbus’s subjects were playing — and indeed placed them officially outside of society, in institutions. The sense of play in these pictures — the “unmanaged faces,” to borrow the art historian Carol Armstrong’s phrase; the earnest and childish costumes — has a utopian quality compared to the seriousness of Arbus’s clearly posed portraits. There’s a reason that Arbus never gave them her usual descriptive yet subtly charged titles, using numbers instead. Sontag wrote, mockingly, that, “In photographing dwarfs, you don’t get majesty & beauty. You get dwarfs.” She held that Arbus failed to use the camera to confer dignity. But the straightness of the picture — unpitying but not unkind — is the point.

The portraits from “Untitled,” as well as those of the socialites at masked balls, and of other flamboyant personalities she encountered on the streets of New York, are often called carnivalesque. (There are actual carnival performers, too.) The term presumably refers to these images’ eclectic subject matter and, to some extent, their style, which is indebted to the visual rhetoric of the sideshow. But what’s truly carnivalesque about these photographs is how they invite us to look at people. The critic Mikhail Bakhtin described the carnival as an upside-down world in which the boundaries between public and private dissolve, hierarchies are overturned, and what’s typically hidden is revealed. All this leads to the fairytale scenarios we encounter in Arbus’s work: child kings, say, or offspring towering over their parents, or “men” being “women.” These surprises have the potential, Bakhtin wrote, to “liberate from the prevailing point of view of the world, from conventions and established truths, from clichés, from all that is humdrum and universally accepted.”

That’s not to say that these photographs are revolutionary — after all, carnivals inevitably come to an end, and normalcy returns. But the photographs do have an undeniable leveling effect, inviting us to take the marginal more seriously than the powerful. Seen all together in the art gallery, they open a space, as Bakhtin put it, for “the latent sides of human nature to reveal and express themselves.” Sometimes grotesque, always beautiful, these revelations upset the oversimplifications on which our social categories rely: if you look too closely at someone else, or at yourself, anything like a coherent identity crumbles.

We’re all freaks, then, but this is hardly a unifying cry — tempting as it may now be to position Arbus as a pioneer of inclusivity and body positivity. In an older, more powerful, and no-less-harsh sense of the word, “freakishness” is a jagged, polysemic eccentricity that reminds us of how much we have to repress and ignore when we say that we know other people. Rather than anticipating the abstraction of difference into diversity, Arbus’s carnival helps us see that what often passes as celebrating difference these days may implicitly reify it. Instead, her images break down the distinction between norm and difference altogether. This is no utopia: it’s as free from judgment as it is free from class, which inscribes the bodies shown in many of these portraits. Looking through Arbus’s lens only makes the encounter more demanding.

“It’s impossible to get out of your skin and into somebody else’s,” Arbus once said. “And that’s what all this is a little bit about. That somebody else’s tragedy is not the same as your own.” Empathy is hard, but accepting its impossibility, or its irrelevance, is harder. The challenge of Arbus’s work comes from the fact that its essential indeterminacy will never allow us fully to disentangle seeing from staring. There is no way of looking that isn’t, in some way, ghoulish. But turning away from that ambivalence would be ghoulish, too.

Max Norman is an associate editor at The Drift.