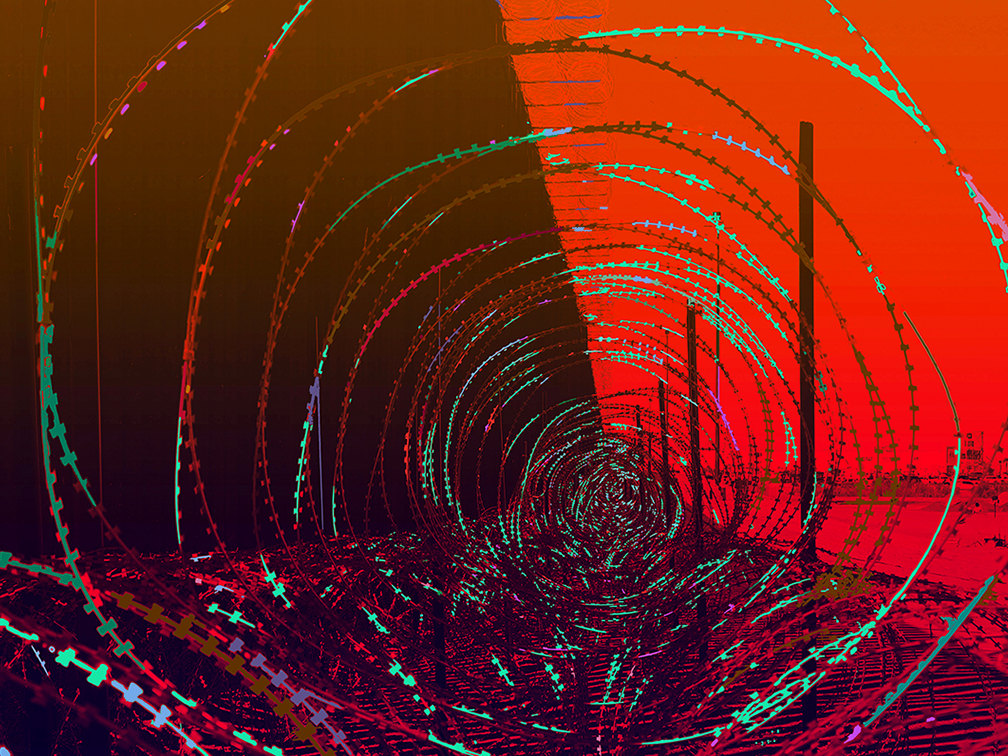

Image by Tony de los Reyes

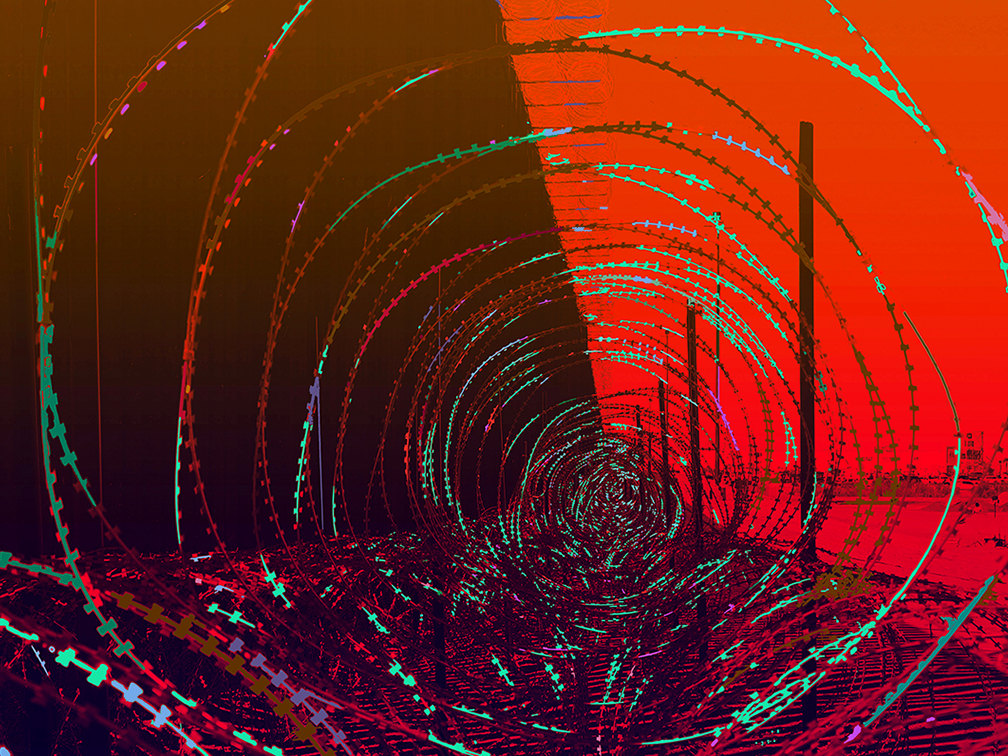

Image by Tony de los Reyes

In September 2020, Dawn Wooten, a nurse at a privately operated immigration detention center in Irwin County, Georgia, filed a whistleblower complaint that alleged “jarring medical neglect” at the facility. The brief was 27 pages long, but it was only the contents of a page-and-a-half (section 4, subsection D) that caught the public’s imagination: hysterectomies conducted without the consent or knowledge of migrant women. Wooten’s account of a “uterus collector” summoned ugly historical analogues: the Tuskegee experiment, the forced sterilization of more than 60,000 people in the U.S. between 1907 and 1973, unsafe clinical testing of the first contraceptive drug on Puerto Rican women in the 1950s — and, across the Atlantic, Josef Mengele’s experiments at Auschwitz. Within days, tweets used terms like “ethnic cleansing”; in neat, shareable bullet points, Instagram infographics summarized the mass sterilization of detainees as if it were established fact; and at the urging of members of Congress, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) launched an investigation.

Some immigration reporters expressed quiet skepticism. Further investigation confirmed Wooten’s claim of widespread neglect, but found evidence of only as few as three hysterectomies. The medical necessity of these surgeries has not been established; it seems likely that they were conducted because bigger procedures lead to bigger payouts. That an unethical gynecologist took advantage of the vulnerability of even one migrant woman is terrible. But it matters that forced hysterectomies were not a widespread, coordinated practice, and that the reason for the abuse may have been more venal than ideological. History repeats itself, but not always in the ways we expect.

The public moved on. The rest of the report was largely passed over — perhaps, as journalist Felipe De La Hoz suggests, because even those who are sympathetic to migrants accept “inhumanity as a distasteful but ultimately unavoidable part of the immigration system.” Many of the allegations — overcrowding, lack of Covid testing, improper or nonexistent quarantining of the exposed, refusal of medical treatment — may have been jarring in their severity, but they were unsurprising to anyone alert to the treatment of incarcerated migrants. The special tragedy is that medical neglect and abuse are rampant in immigrant detention, a situation exacerbated by the pandemic, but it is sensational, novelistic cruelty that attracts outrage. And when the outrage wanes, whether because of attention spans or factual revisions, the larger problems remain unexamined.

This pattern is typical of immigration discourse among liberals and progressives alike, albeit with slight variations. In 2021, images and videos of Border Patrol officers on horseback appearing to use reins as whips to disrupt a camp of mostly Haitian migrants at the southern border spread online, accompanied by comparisons to violence against black people before and after the abolition of slavery. The uproar incited by the image failed to materially improve the migrants’ condition: most of them were deported. The casual barbarity of the Border Patrol, present since its inception, has continued unabated.

Focusing on isolated events is one way to maintain the fiction that fundamental differences exist between the political parties on immigration. When the Trump administration announced its “zero-tolerance” policy and reporting exposed the resultant separation of thousands of children from their parents, there was justified outcry. Under “zero-tolerance,” all adults who crossed the southern U.S. border were to be prosecuted for “illegal entry,” a federal misdemeanor which had been inconsistently prosecuted in the past. Because children cannot be held in federal criminal detention, the adults would be detained, and the children — no matter how young — classified as “unaccompanied minors” and placed in the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Photos and videos of weeping children and parents galvanized the public; a slogan became a hashtag and then a nonprofit: “Families Belong Together.” Under the Obama administration’s gentler hand, entire families had sometimes been held in Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities, a form of child incarceration legally permitted because it is civil rather than criminal detention. Families belong together — in cages. The response to the Trump administration’s immigration practices reveals, alongside genuine horror, a liberal desire to see his team as uniquely cruel. But policies that divide families — especially internal immigration enforcement and deportation — began before Donald Trump and have continued after him.

Outrage (justified or not) that fails to provoke deeper inquiry can be attributed to many oft-invoked origins of contemporary woes: misinformation both accidental and deliberate, social media’s wildfire capability, and an essential human desire for easily comprehensible, and thus solvable, problems. But there is another, subtler cause, particular to U.S. immigration. Rhetoric obscures policy, which enables the perseverance of a system that — regardless of administration — brutalizes legal and illegal migrants alike. Within the context of the nation-state, who should immigrate and how they should immigrate is a political question. Yet a discourse that avoids delving into policy and history makes the politics petty and provisional. It also leaves significant questions — especially about the logic of state sovereignty undergirding the system — unasked.

Before taking office, Joe Biden campaigned on promises of “securing our values as a nation of immigrants” and sharply criticized Trump’s immigration policies, leading many to expect that he would reverse course. In some cases, he has. Biden is attempting to halt one of his predecessor’s signature efforts: the Migrant Protection Protocols, otherwise known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, which mandates asylum-seekers who passed through Mexico on the way to the U.S. return to Mexico to await judgment on their cases, even though many are from countries farther south. (Biden’s 2021 effort to end the policy was thwarted when two states sued the administration to keep it in place. In late April, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case.) At the same time, Biden’s handling of a Trump-era interpretation of a hitherto obscure public-health provision, Title 42, suggests a more fundamental continuity between the two administrations.

A wholesale ban on immigration imposed by the Center for Disease Control in 2020, Title 42 is almost universally considered a failed policy that has done nothing to alleviate the effects of the pandemic. From the beginning, it has been both an empty performance of action and a pretext for the immediate expulsion of asylum-seekers — since its inception, some 1.7 million people have been expelled into northern Mexico without being processed. Many expected Biden to end Title 42 immediately after taking office; instead, his CDC didn’t announce a plan to end the policy until April 2022.

The lag is telling: fulfillment of the legally guaranteed right to apply for asylum is subordinated to political self-preservation (or at least its pursuit). And the administration’s supposedly liberal-minded efforts to resolve obvious problems in the asylum system are flimsy on closer inspection. Recently, DHS outlined its plan to address the backlog of pending asylum cases, which as of early 2022 numbered more than 670,000. (Total pending immigration cases now amount to nearly 1.8 million.) At present, migrants undergo a “credible fear” interview with an asylum officer and then are either removed or released until their cases are heard in an immigration court. Under the new rule, migrants who pass the first interview will, after 45 days, be called for a second interview with an asylum officer, who will make a final judgment. (Denials can be appealed to the courts.) Some immigrant advocates argue that reducing asylum-seekers’ time to form a coherent case and find legal representation (which historically increases the likelihood of being granted asylum) simply fast-tracks deportations. But the new rule, in an apparent approximation of due process, also adds a step — two interviews instead of one — and it is unclear whether it will actually streamline, rather than complicate. The solution, whether one’s goal is creating a more efficient system or giving migrants the best chance of being granted asylum, comes to seem more like sleight of hand.

Both administrations have shown themselves willing to weaken the right to asylum and to pursue policies that stop migration. Their actions betray the same view that America is “a nation of immigrants” — just not these immigrants. The most significant distinction between the administrations may be the most obvious one: that, under Trump, rhetoric and policy aligned. Trump was an imprecise orator, a bloviator who preferred the sweeping declarations that would get him coverage on cable news to explanations of actual policy, but the ideological position was almost always clear — and the policies reflected his stated priorities. Biden returns us to an earlier, Obama-era strategy. Obama catchily refocused deportation on “felons, not families.” Nonetheless, he deported more than three million people, an increase of one million over the Bush administration numbers. If liberals are less outraged in general about immigration policy now that Biden is in office, it is because this paradigm is more familiar: say one thing, do the opposite. There’s little need to disguise the deception, because hardly anyone is paying attention.

And even if liberals on some level realize that the rhetoric of acceptance and inclusion is merely a sheen on the surface of a dark pool, it is more comfortable to believe what’s told and ignore what’s done — at least until another viral photo emerges. The tension between rhetoric and enactment resembles, in an odd way, the border wall that Trump raised again and again in speeches: something more crucial as symbol than reality.

It might be shocking to suggest that liberals and progressives could take Stephen Miller, Trump’s xenophobic policy architect, as a model. But if there’s any cure for the cycle of useless liberal outrage, or any chance of remaking the immigration system, it paradoxically may lie in Miller’s example. Miller’s opponents characterized him in terms so hyperbolic that one would be forgiven for thinking he was a comic book-style supervillain rather than a man with the unassuming title of “senior policy advisor.” A background in communications and a hunger for conflict made him willing to fight on cable news and shout across conference tables, but if Miller had a superpower, evil or not, it was the ability to manipulate existing political and bureaucratic structures. As Julie Hirschfeld Davis and Michael D. Shear report in Border Wars, he understood the immigration system as “ancient sedimentary rock — layer upon layer of policy decisions, executive memoranda, legal interpretations, and day-to-day practice.” His mastery of arcana, acquired over nearly a decade working on anti-immigrant policy, alerted him to the power of strict execution of the law. As Davis and Shear recount, Miller directed his immigration task force to pore over existing rules in search of “grounds for inadmissibility that were not being enforced.”

Miller did want to change laws, but he came to understand that existing regulations were available not only to enforce but to broaden as well. He saw family-based immigration, which is the only category of U.S. immigration without a numerical limit, as a gateway ready to be gated shut. However, as he discovered with the “Muslim ban” (a 2017 executive order that, among other restrictions, barred nationals from seven Muslim-majority countries from visiting the U.S.), rewritten two times before it could measure up to Supreme Court scrutiny, radical changes and outright bans were difficult to impose. While he did not give up on sweeping changes, he understood that shifting the “sedimentary layer” was not only easier but sometimes more effective, given the high level of scrutiny and administrative burden of creating new regulations. To attack family-based immigration, Miller focused on strengthening the “public charge” rule, which requires immigrant applicants to prove they will not become burdens to the state — that is, make use of such public services as Medicaid and cash or food assistance programs. Increasing the burden of proof on immigrant applicants and U.S. sponsors would result in more denied applications — and, perhaps, it would also discourage many from applying at all. (The proposed changes, which went into effect in early 2020, were annulled a year later.)

Miller was perhaps most successful in decimating refugee admissions, again by manipulating the existing bureaucratic mechanisms. In addition to reducing the annual cap on refugees the U.S. would accept to its lowest levels since inception, the Trump administration slowed the interview process for refugees abroad, required stricter vetting, and deliberately understaffed the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program and U.S. consulates. Biden has been unable to quickly restore these destroyed processes and gutted departments. Only 11,000 refugees were admitted in fiscal year 2021, and admissions have been slow in the first half of fiscal year 2022. Miller didn’t get everything he wanted, but he got a lot — and he got it by excavating those layers of policy and process and history until he could see the system as a web, a complex whole, rather than a set of random events.

Whether the goal is to change or simply to understand the realities of U.S. immigration, it’s necessary to follow Miller’s example and dig through the layers: beneath the rhetoric, the policy; beneath the policy, the process; beneath it all, the historical contingencies and the logic that have shaped it.

Positions on immigration policy probably resemble a chiliagon more than a spectrum, but much of the rhetoric on all sides focuses on “illegality.” “Illegal immigration” is a category created, as scholar Mae M. Ngai writes in Impossible Subjects, by the existence of immigration restriction itself. Its invention, she writes, “produced the illegal alien as a new legal and political subject, whose inclusion within the nation was simultaneously a social reality and a legal impossibility — a subject barred from citizenship and without rights.” Ngai’s analysis frames the “illegal alien” as the “impossible subject,” the person who cannot exist by ruling of the state but who nonetheless participates in the life of the nation. Even supporters of immigrants’ rights tend to concede the primacy of legal status, arguing for exceptions because of immigrant virtue, common humanity, or flagrant injustice. Another favorite catchphrase among liberals, “No one is illegal,” is an empty assertion that does not address the policies that mean some people are, in fact, illegal in presence if not in essence. (As long as the nation-state is the defining identity for populations, borders — and therefore some restrictions on who is allowed to cross them — are unlikely to disappear.)

Restriction of immigration produces not only the “impossible subject,” but also an attendant bureaucracy, the paperwork that divides people into “documented” and “undocumented.” Once created, requirements for proving legality accrete, for citizens as well as non-citizens. Documentation of the right to be wherever we are governs our lives in ways we mostly don’t consider or question. It is perhaps usual to conceive of the immigration system in terms of borders and lines, but everyone is incorporated into it, in the many ways legal status is proven and reinscribed. Ngai writes that there has been a “collapse” of border and interior. To an extent, this can be interpreted literally. The jurisdiction of U.S. Customs and Border Protection extends 100 miles inland from any “external boundary,” land or sea, which means that nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population lives within it. ICE can arrest anyone almost anywhere, its jurisdictional authority complicated and often amplified by its entanglement with local law enforcement agencies. But there’s a conceptual collapse as well: restricting immigration creates a need to differentiate, to determine who is present, for how long, and what the presence permits. In some sense, the border is less a feature of the land than of the air we move through and carry with us.

When immigration regulations were first instituted in a young United States, in 1790, they focused on who could be naturalized rather than who could enter. (Naturalization is the process of acquiring citizenship, whereas immigration is a broader category that includes who is allowed to enter the country, and in what capacity, as well as who can leave, i.e., through the issuance of passports and the existence of exit controls.) In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, naturalization restrictions tightened and loosened and tightened again; as migrants arrived in larger and larger numbers, restrictions on immigration, largely defederalized before, came into effect. At first, these restrictions focused on individual characteristics (forbidding, for instance, the potentially indigent) and relied on the discretion of authorities at ports of entry, who conducted individual inspections. The first explicitly nationality-based restriction was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which came into effect around the same time as federal appropriations and enforcement for deportations.

A regime of documentation that feels recognizably contemporary emerged in the 1920s, when a radical revision of immigration law led to nationality-based quotas on immigration that were intended to maintain the country’s existing racial and ethnic balance. In what would become a significant point of contention, no numerical restriction was placed on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico; as more and more Mexicans migrated north, whether permanently or not, something like the modern anti-immigrant line developed, with Mexicans depicted as dirty, disease-ridden, uneducated laborers undercutting U.S. citizens by working for low wages. Officials sought now-familiar kinds of bureaucratic workarounds: enhanced scrutiny of applications from Mexico, as well as a rule that adjusted the status of certain “illegal aliens” who crossed into Canada before re-entering.

The early twentieth century also remade the border itself as a site of violence: now a migrant could expect to encounter humiliating and punitive requirements for entry, including on-site gasoline bathing and delousing, the inspection of naked bodies, haircuts, and the fumigation of clothes and belongings. Perhaps the most preposterous of documentations, bathing certificates, emerged, along with their own black market, resulting in an increase of ingeniously “unlawful” border crossings. The 1920s additionally saw the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol, a group of officers so bestial and unprofessional in their treatment of everyone that civilians and politicians protested their behavior. The right documents were no guarantee of better treatment: in the 1930s, the U.S. forced the “repatriation,” or outright deportation, of at least 400,000 people of Mexican descent, at least a quarter of whom were U.S. citizens.

Among the documents and procedures now taken for granted are passports and border checkpoints, which became common only during and after the First World War. Conflict between nations made even visitors and short-term migrants seem like an existential threat, and European countries began to revoke citizenship from people of “enemy origin.” This meant that even as World War I redrew boundaries, it also reified the nation-state as the fundamental category of identification and established as an unshakeable norm the documentation of entry and exit.

The war’s upheaval created an enormous number of refugees as well as stateless people who lacked the documentation required for free movement. Anxiety over the presence of these people grew, even across the Atlantic. Decades before the United Nations’s “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” as Ngai has argued, following Hannah Arendt, the rights of the citizen or the “national” (a newly created category) began to be legally enshrined, a process that had the unintended consequence of eroding the prevailing Enlightenment idea that rights were innate. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt writes that the war represented the “end of the rights of man.” Ngai phrases it differently, though no less definitively: “The concept of inalienable individual rights, central to European political philosophy, was shown to inhere not in human personage, after all, but in the citizen, as rights were only meaningful as they were recognized and guaranteed by the nation-state.”

The state’s ensuing need to monitor and record such rights, and their limits, engendered a “legal” immigration system with its own distinct brutality, a different violence from the kind that tends to go viral. The cruelty is sometimes attributable to specific policies and practices, such as “Remain in Mexico,” the lack of guaranteed representation in asylum cases, or — less dramatically — simply the fees required throughout the immigration process. (The United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) is a self-funded government agency; application and petition fees support its operations.)

Bureaucracy, as Miller recognized, is the most powerful weapon in U.S. immigration. Once set in motion, it continues to deploy itself. In a recent conversation, a senior official at USCIS, speaking on background, explained how bureaucratic processes generate more bureaucratic processes, each new step creating the possibility of adding another step to justify the previous one. Whether or not bureaucratic multiplication is a side effect of a human quest to attach meaning to a process, it remains true that, as the anonymous official told me, “bureaucracy is often the cruelest part of our immigration system.” Once in place, new steps are hard to walk back because doing so depends on staffing and technology as well as political will.

This is evident in the case of visa processing times, where wild variations — and sometimes severe delays — are a source of instability and stress for applicants of all types. In 2012, after Congress failed to pass the DREAM Act, which would have provided a path to citizenship for people who were brought to the U.S. as children and still lack legal authorization, the Obama administration created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Under DACA, Dreamers gain legal authorization to live, work, and attend school in the U.S., but no path to citizenship and limited ability to travel outside the country. And DACA authorization lasts for two years at a time, so participants must plan their lives in two-year intervals, and live in a constant state of reapplication. Processing times can also render certain visas irrelevant; despite the popularity of 90 Day Fiancé, the K-1 visa, a non-immigrant visa that allows the fiancé of a U.S. citizen or permanent resident to enter the country for 90 days, is almost always useless. It can take as long to process as an I-130 spousal visa, which grants the spouse of a U.S. citizen or permanent resident the right to immigrate.

For the most vulnerable applicants, the slow pace and exponential regulations of immigration bureaucracy are the most onerous. Acquiring asylum or refugee status usually takes years and hundreds if not thousands of pages of documentation. And the government’s treatment of refugees and asylum-seekers is an area where symbolic gestures flourish. Despite the Biden administration’s recent pledge to take in 100,000 Ukrainian refugees (of the six million who have so far fled the country), both reporters and officials admit this number is pure rhetoric, meant to signal a willingness to accept refugees, rather than a target the current bureaucracy will be able to meet. While the political will to admit refugees may be greater with Ukrainians than with the Afghans seeking resettlement after the U.S. withdrawal in 2021 (as many have pointed out), the bureaucratic process is unlikely to be markedly friendlier. Even those it favors, it punishes.

If the bureaucracy that runs immigration is arbitrary and cruel, then what of the laws that gave birth to it? The contemporary immigration debate often transforms facts into fundamental realities: things that must be rather than things that are. But even a brief examination of legislative history reveals the arbitrariness of the laws we have today.

In 1965, Congress passed the Hart-Celler Act, the last truly radical reshaping of U.S. immigration by the legislature rather than the executive. The act abolished the “national origins” quota system, which until then maintained the existing racial and national balance by calculating each nationality’s share of the population using the U.S. census, and then applying that percentage to the overall immigrant quota. As the Civil Rights Movement grew and immigrants from southern and eastern Europe gained political influence, this system had begun to be widely criticized as discriminatory and outmoded. Hart-Celler kept hard limits, setting a cap of no more than 20,000 visa issuances annually from any one country, an overall limit of 170,000 quota slots from the Eastern Hemisphere, and for the first time restricting immigration from the Western Hemisphere to 120,000 annually. The only exception to the limits were visas for close relatives of U.S. citizens and permanent residents.

This was a move toward equality that also cemented numerical restriction as the norm for immigration regulation. Even if the counting was no longer discriminatory, there still were quotas — the first 20,000 people are legal, and the 20,001st is not. Such a system’s relative inelasticity made it difficult to respond to changing conditions that over time have influenced the actual number of migrants. The need to address unexpected flows has contributed to the number of ad hoc policy revisions that remain, whether useful or vestigial, after the situations they were designed to address have passed. It has also increased the discretionary powers of immigration officials, giving them latitude to respond to situations in which rules or quotas are inadequate.

Historical inflection points like the Hart-Celler Act matter, but the system’s incremental negotiations are perhaps more important to truly understanding it. Take the cases of Puerto Rico and the Philippines: when the U.S. acquired both archipelagos after the Spanish-American War in 1898, the prevailing understanding across the political spectrum was that the U.S. would not be a permanent colonizer. Colonization was seen to be anathema under U.S. law going back to the Constitution, and it was thought that any territory taken must be incorporated into the union, with inhabitants eligible for naturalization. The Fourteenth Amendment states that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States,” but many would-be colonizers had no interest in admitting new non-white citizens. (The majority of Puerto Ricans were considered white, but this was not the case for Filipinos — and whatever rule applied to people from one colony would have to extend to people from the other.)

In the first 30 years of the twentieth century, citizenship was slowly but surely decoupled from subjecthood: it became possible to reside legally in the U.S. or its territories and have no other foreign allegiance and yet not be fully incorporated into the body politic. At first, Puerto Ricans were required to forswear allegiance to Spain and take the same oath of allegiance to the U.S. that was typically recited during naturalization. When some Puerto Ricans argued that the oath had made them citizens, the government stopped requiring it. But once they no longer had to renounce a foreign allegiance, they were ineligible for naturalization on a technicality that was later removed, in 1906, under pressure from Puerto Rican pro-statehood advocates. When 1934 legislation granted independence to the Philippines (largely to prevent a mass influx of Filipino migrants), it reclassified all Filipinos, including those already in the U.S., as “aliens for the purpose of immigration” and established an immigration quota so low as to be an obvious insult: 50 Filipinos a year. Meanwhile, Puerto Rico still maintains a permanent tie to the U.S. without federal representation or the promise of future statehood.

But what would our immigration system today look like if, instead of hollowing out the Fourteenth Amendment with technicalities, legislators had embraced its radical promise? We forget that the southern border, so fraught today, was largely considered unimportant to regulate before the late nineteenth century; that regimes of control over movement are fairly young and developed under specific historical pressures; that the concepts of both migrant and citizen, though ideologically influenced, are defined by a push and pull between the state and its subjects. The progress of immigration, like the progress of the U.S. itself, is falsely conceived of as teleological, rather than subject to myriad pressures. It is important to remember that every aspect of its regulation could have been — perhaps could still be — other than it is.

That the system developed and continues to develop in an ad hoc, historically contingent way might suggest that there is no design to its malice. But beneath these eddies of history is a deeper current that drives restriction toward more restriction: the logic of state sovereignty. As Attorney General of California, Earl Warren was one of the architects of Japanese internment, which incarcerated some 120,000 people, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens. Citizenship was no protection because, as Warren reasoned, with “the Caucasian race” it was possible to tell if someone was loyal or lying, but not with the Asian other. A little over a decade later, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, he wrote in a dissenting opinion that the very existence of a stateless person “is at the sufferance of the state within whose borders he happens to be.” Echoing Arendt, he reasoned, “Citizenship is man’s basic right, for it is nothing less than the right to have rights.” One might think this reflects a change in views from the 1940s, but until a couple of years before his death in 1974, Warren resisted expressing regret over his role in the treatment of Japanese Americans, calling it “a matter of history.” That the same man could annul the rights of so many citizens and yet so powerfully defend citizenship seems contradictory, but it’s a reminder that, on the subject of immigration, rhetoric and policy tend to diverge.

In 1948, the UN set out a person’s “basic rights and fundamental freedoms.” One of these was “freedom of movement,” the right to move freely from place to place, but it confined that freedom “within the borders of each state.” Another right included in freedom of movement is similarly defined through the nation and bounded by its borders: that a person has the right “to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his own country.”

But what, in any case, makes a country one’s own? Birth, many would argue, or blood, or a documented legal process that leads to “being naturalized.” Each of these has been at some point questioned or contested as an avenue to belonging. The debate surrounding naturalization has often been whether that fundamental transformation from stranger to native is, in fact, possible. The standard racist and xenophobic answer is no. A more moderate answer appeals to the assimilability of a person or population, imagining a “melting pot.” Another answer relies on documentation: to be made native is to acquire the papers that say one has been made so, whether at birth or later in life.

But if we deny a distinction between the native-born and the non-native, it might be easier to recall that the immigration system includes everyone, even those with citizenship jus soli (by birth on a nation’s soil) or jus sanguinis (by blood inheritance). And whether or not you are claimed by a state, you are at its mercy, as you are at the mercy of the overall system of state sovereignty. While it may seem like pure alarmism to invoke deportation, internment, or revocation of citizenship for anyone — even a person born on U.S. soil, with parents born on U.S. soil — citizenship has been historically malleable, subject to many changes and redefinitions over time. Its rights and privileges are as unstable as they are constitutive. A paranoiac mindset is appropriate.

It is touching to read the repeated lawsuits brought against the U.S. by people who were, for various reasons at various times, prohibited from being naturalized. Touching because, while a few of the cases reached the Supreme Court, all of them failed to accomplish the goal of redefining citizenship. But the number and range of individual efforts to contest the state’s determinations reflects something that is admirable, if also perhaps pitiable: a refusal to accept terms that conflict with how and where people want to live just because those terms exist.

And yet, this pattern of reaction, however inspiring it is as a display of human spirit, is flawed — like that natural, reactive outrage over forced hysterectomies and men with whips on horseback. It is hard, whether working with a conventional definition of immigration or a bigger one that encompasses all of us, to know how to think or act within the cacophony and the paperwork. Perhaps the first thing is to abandon outrage, not because it is unjustified but because it is profoundly individual, rooted in the selfishness of dramatized empathy. The next step is to ask what’s actually happening and why, why, why.

Elisa Gonzalez is the author of Grand Tour (2023). She lives in Brooklyn.