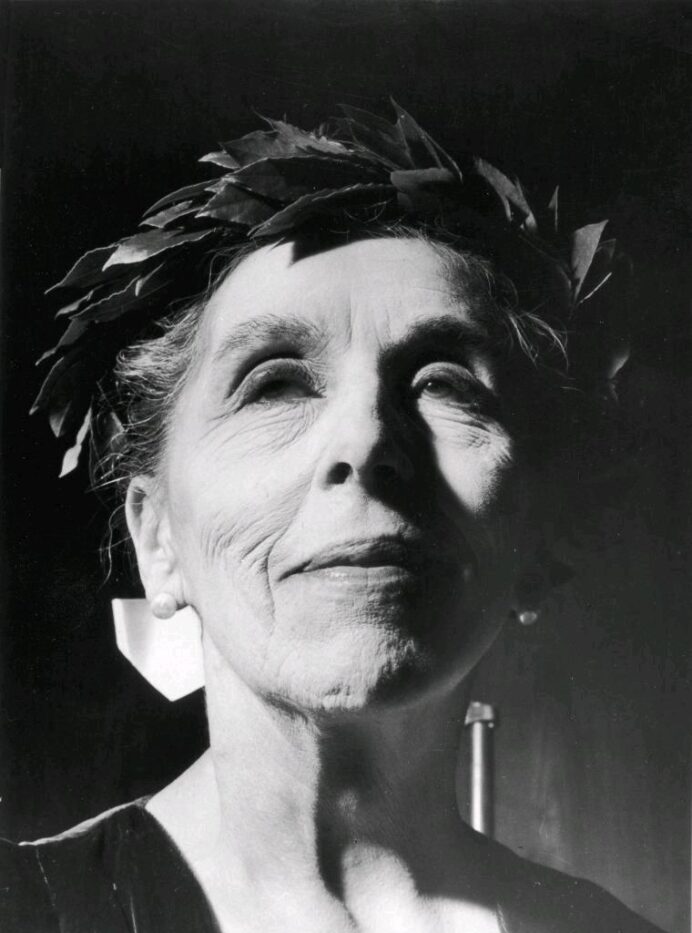

Karen Blixen receives the Golden Laurel award in 1952.

Karen Blixen receives the Golden Laurel award in 1952.

After Kenya declared independence from British rule in 1963, there came a flood of renamings. Schools, suburbs, and roads were rechristened in ways that spoke to a new idea of what it meant to be authentically Kenyan. In Nairobi, “Queens Way” became “Mama Ngina Street,” and roads named after the first four colonial commissioners were redesignated for African leaders: Dedan Kimathi, Muindi Mbingu, Daudi Dabasso Wabera, and Mbiyu Koinange, respectively.

One appellation that escaped the fate of the rest was “Karen” — the name of a Nairobi suburb, presumably christened for the Baroness Karen Blixen, the Danish writer also known as Isak Dinesen. Karen Estate lies seventeen kilometers west of the city centre and is one of a few Nairobi suburbs where tall jacarandas loom large, straddling long driveways onto huge mansions with plush gardens. It hosts diplomats, powerful business people, the upper strata of Kenya’s political class, expatriates, and much of Kenya’s privileged white, Asian, and Black populations.

Karen’s contemporary ethos was unintentionally revealed in a New York Times Style story about the suburb’s upscale boutiques in which every single shop-owner and fashion designer mentioned is a white woman, including the Swedish proprietor of a shop called “Bush Princess.” Karen, we learn, is “home to some of the city’s most intriguing and exclusive places to shop.” The two African women pictured, only one of them named, are both floor staff. The colonial undertones are even less veiled in a 1985 story in The Washington Post that devoted copious print inches to explaining the pains white homeowners in the “horsey suburb” took to protect their houses and “well-trimmed hedges” from Kenyan robbers. In Karen today, you can breakfast with the endangered Rothschild giraffes at Giraffe Manor, or adopt an elephant at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. And, of course, you can visit the Karen Blixen Museum, in the house where the baroness once lived.

Karen Blixen, a Danish aristocrat, moved to Kenya at the height of Empire, in 1913, with her new husband, 15,000 Danish crowns, and the intention to start a coffee farm. It was only later, after she returned to Denmark in 1931, that she gradually found fame as a writer. Her 1937 memoir, Out of Africa, offers a record of her time in Kenya, detailing her relationships with her lovers, her servants, and the two thousand “Natives” who lived on her farm. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the grand old man of Kenyan letters, later wrote, “As if in compensation for unfulfilled desires and longings, the baroness turned Kenya into a vast erotic dreamland in which her several white lovers appeared as young gods and her Kenyan servants as usable curs and other animals.”

And dreamland she made it. On safari, Blixen’s servants carried bathwater to her on their heads across the plain, and, she writes, “when we outspanned at noon, they constructed a canopy against the sun, made out of spears and blankets, for me to rest under.” She imagines herself a judge to the Kikuyu squatters, claiming at one point that she looks at her cook “with something of a creator’s eyes.” To Blixen, the Africans existed if not quite at the level of the bush animals, then somewhere just above them. “The Natives,” she writes, “could withdraw into a world of their own, in a second, like the wild animals which at an abrupt movement from you are gone—simply are not there.” She believed that “the umbilical cord of Nature has, with them, not been quite cut through.”

Deserted by her husband, Karen threw herself into the hedonistic social life available to the European gentry in the colony. When the Duke and Prince of Wales came to visit, she made the local Kikuyu perform a dance in their honor. She and her lover, British big game hunter Denys Finch-Hatton, oscillated in and out of the “Happy Valley set,” described by Ulf Aschan, the godson of Blixen’s husband, as “relentless in their pursuit to be amused, more often attaining this through drink, drugs, and sex.” A popular question among British aristocrats at the time was, “Are you married or do you live in Kenya?” None of this appears in Blixen’s memoir, which skips over wild parties in favor of providing lush detail about the landscape and the “Natives.”

In The New York Review of Books, American critic Jane Kramer called Out of Africa “without a doubt the most irresistible prose ever written about East Africa.” A bestseller, it was selected for the Book-of-the-Month Club, included in the Modern Library series “100 Best Nonfiction Books,” and translated into multiple languages. Blixen’s name was regularly floated as a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature. When Ernest Hemingway — a regular hunting partner of Blixen’s husband, Bror — won the prize in 1954, he suggested it should have gone to her instead. (She was reportedly closest in 1961, when she was passed over for Ivo Andrić.)

In 1985, the memoir was adapted into a film directed by Sydney Pollack and starring Meryl Streep and Robert Redford. The plot, which draws on several additional sources including Blixen’s second memoir, Shadows on the Grass, and Judith Thurman’s biography of Blixen, is primarily focused on Blixen’s romance with Finch-Hatton. It brought in $227.5 million at the box office and swept the Oscars, winning seven awards including Best Picture and Best Director, and propelling the image of Kenya as a romantic gateway into popular imagination.

The year after the film’s release, Kenya saw a dramatic spike in tourism (from 152,000 visitors to 176,000 in a single year), and the house Blixen once lived in was converted into a museum. By 1987, the tourism sector had become a tentpole of Kenya’s economy, bringing in approximately $350 million annually. By the end of the decade that figure had grown to $443 million per year, roughly 40 percent of Kenya’s total foreign exchange.

Barack Obama recounted his first visit to Kenya in 1988, writing that he suspected some tourists “came because Kenya, without shame, offered to re-create an age when the lives of whites in forest lands rested comfortably on the backs of the darker races.” He was struck by Nairobi’s stark racial hierarchies, something he hadn’t anticipated seeing in his father’s homeland. “In Kenya,” he wrote, “A white man could still walk through Isak Dinesen’s home and imagine romance with a mysterious young baroness.”

Prior to the violence of colonialism, the 6,000 acres Blixen called her own had belonged to the very “Natives” about whom she rhapsodized in her memoir. Wanton theft is at the core of colonial Kenya, which the British established as a settlers’ frontier, parceling off land to European adventurers. The first batch of settlers received their land grants in 1902. It included British aristocrats like Lords Delamere, Hindlip, and Cranworth, who set the gold standard for a gilded countryside hunter lifestyle. Later, the British government expanded lease offerings and exempted settlers from the land tax, and in 1920, the protectorate officially became a colony. But coffee and cattle, the colonial industries of choice, were expensive to produce, and Kenya earned a reputation as a “big man’s frontier,” a place where only the extremely wealthy could afford to settle.

The Blixens were part of this wave of settlers. Their land, previously Maasai pastoral country and Gikuyu farmland, became “a farm in Africa at the foot of the Ngong Hills” — Out of Africa’s famous opening line. Ngũgĩ calls settlers like the Blixens “parasites in paradise.” He writes, “Kenya, to them, was a huge winter home for aristocrats, which of course meant big-game hunting and living it up on the backs of a million field and domestic slaves.”

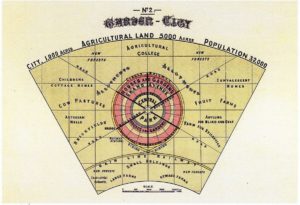

With its warm climate and its stunning landscapes, colonial Kenya was an attractive getaway for European aristocrats looking to escape the winter chill, and colonial planners catered to their needs. In his 1902 book, Garden Cities of To-Morrow, the British urban planner Ebenezer Howard had laid out his ideal “garden city,” which combined the best features of urban and rural life. The parts of Nairobi that were segregated for whites were planned as garden cities, with deliberate care taken, for instance, to plant jacaranda trees en masse.

Meanwhile, Africans were consigned to live in what the architectural historians A. M. Martin and P. M. Bezemer have called “villages on garden city lines.” Africans were not even allowed to settle permanently within city limits. Their settlements, along with those of the Indian workers brought in by the British as railway builders, were viewed as potential public health threats to Europeans and deliberately placed far from white suburbs. A 1941 report by the African Housing Board proposed that this housing strategy would teach “Native” residents to observe elementary rules of hygiene. In white Nairobi, safe from the scourge of non-Europeans, residents could live charmed existences in a green paradise. It’s an idea — and a marketing strategy — that persists for both tourists and residents: Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenya’s President and the scion of the nation’s richest family, made headlines in December for affirming his commitment to restoring Nairobi’s worldwide reputation as a “Green City in the Sun.”

After the Great Depression, Blixen was forced to leave Kenya and sell her family’s now-bankrupt plantation, Karen Coffee Company (which, confusingly, was either named after Blixen or her cousin). The buyer, developer Remi Martin, subdivided the land into ten- and twenty-acre plots and kept the name “Karen.” Heralded by advertisements in the early 1930s as a place for “contentment in retirement,” the new estate boasted such activities as golf, tennis, polo, fishing, and shooting. “All the Amenities without the Disadvantages of Town,” one advertisement read. Here was the ideal garden city.

I live in Machakos, a county to the east of Nairobi, but I went to college in Nairobi. I recently decided to visit Karen, on the far end of the city. As a Black Kenyan man, it’s likely that if I were to walk alone in Karen, I’d be questioned and asked for identification. This is not particular to Karen; all the wealthy neighborhoods in Nairobi are rife with physical barriers and security guards who carefully screen visitors. Before independence, an African was not allowed inside Nairobi without a permit and a kipande (a metal plate worn around the neck detailing basic personal details, fingerprints, and employment history), and in neighborhoods like Karen, discrimination persists against those assumed not to belong.

In light of its sheer expanse and my lingering fear that I’d be stopped, I asked a friend to be my guide. Linda, who is Black and lives in Karen, agreed, and we drove around the suburb, playing tourists in colonial Nairobi, before heading to the museum. The estate is picturesque: potted plants hang from street signs, and tall croton trees hide old English colonial bungalows. On one road, a sign announced, “No Horses Allowed Beyond This Point.” A gate bore a placard reading, “Out of Africa.” As we drove, we talked about the “Karen Cowboys,” a group associated in Nairobi with the Karen Estate.

Perhaps no figure better illuminates the links between contemporary Kenya and its colonial past than the Karen Cowboy. Sometimes also called Kenyan Cowboys, KCs are descendants of European colonialist-settlers, and they, as Linda put it to me, “live in a separate universe.”

KCs are modern-day descendants of the Happy Valley set. Their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents came to Kenya and acquired land as participants in the violence of the British colonial project. They revel in the settler-colonist aesthetic, keeping horses, dressing in cargo pants and safari boots, and driving old Land Cruisers and Land Rovers. Families maintain accounts at the Karen Provision Store, and children are sent to posh British-curriculum schools in Nairobi. Some are cash-poor but asset-rich, with land that has “always” been in their families — frequently this includes luxury tented camps at the Maasai Mara, Kenya’s premier safari destination. Many have a wealth of information about the country of Kenya and can speak Swahili, but keep themselves isolated from the Kenyan population. As Susan, a British-born white woman who moved to Karen in the 1970s to marry an African man, explained, KCs are characterized by their ‘cowboy lifestyle.’ “They go on safari, go drinking, go riding, have fun,” she said. “That’s what’s important to them.”

One of the more publicly recognizable avatars of KC culture was Tom Cholmondeley, the Nairobi-born, Eton-educated great-grandson of Lord Delamere, one of colonial Kenya’s earliest British settlers and “progenitor of Kenya’s most famous white family.” Cholmondeley was convicted in 2009 of killing stonemason Robert Njoya on his family’s 50,000-acre ranch. Njoya was the second Kenyan man Cholmondeley had shot and killed in as many years, claiming self-defense against potential robbery and poaching. His girlfriend Sally Dudmesh, a British jewelry designer and member of the “hard-partying expat set,” visited him regularly during his nearly four-year stint in prison. “For me, it really feels like I’ve been in prison,” she complained to the Evening Standard. “I’m really suffering. This is beyond what a human being can tolerate.” In fact, Dudmesh lives at The Ngong Dairy, the house in Karen that was used as Blixen’s in the film Out of Africa. As she once said in an interview, to her, Kenya represents “a sort of wildness, a spirit of adventure. There’s an incredible freedom and scope to Africa that you don’t find in England.”

Often, KCs champion animal conservation, painting the often-poor pastoral communities who live in proximity to conservancies as poachers and destroyers of the environment and wildlife. This mode of conservation, prominent Kenyan carnivore ecologist Mordecai Ogada has argued, “Remains firmly in the ‘Victorian gamekeeper’ mode,” where conservation is about protecting wildlife from lower classes so that the elite can enjoy the wildlife for themselves. Most of the sanctuaries in Kenya are owned by settler families who stayed in Kenya after independence, gaining Kenyan citizenship, or by people who subsequently bought them from the settler families. The latter group consists largely of wealthy Europeans and African members of the ruling class.

Though Karen Estate remains a colonial-aristocratic suburb, it’s not immune to change. Some of the old houses, with stables ensuite, have been demolished and replaced with apartment complexes. Cabro roads have been laid, and townhouses erected. There are malls now, and other developments afoot. In response, the Karen Lang’ata District Association, arguably the most powerful homeowners’ association in Kenya, has swung into action. Established in 1940, the Association’s mandate is to fight perceived threats to the prestige of the suburb. These threats include footpaths that serve as access routes for low-income laborers (the association has called them getaway routes for criminals) and kiosks that offer affordable supplies (hideouts for criminals).

And not everyone who lives in Karen today is white. No longer the exclusive enclaves of rich Europeans, the neighborhood is now the almost-as-exclusive enclave of rich and upper-middle-class Europeans, Asians, and Africans. I spoke with Naila Aroni and Dana Osiemo, two Black Kenyan women in their twenties who grew up in Karen, where Black families were the exception. Both told me that informal segregation was common during their childhood, and that they and their friends still avoid going to certain white-frequented places. “You hear how some white people think that too many Black people are moving in so they want to move out because the place is being spoilt,” Osiemo recounts.

A combination of nonwhite house owners, the proliferation of apartment blocks, and the encroachment of urban Nairobi has shifted the colonial-aristocratic ideal 250 kilometers north, to the plains of Laikipia, which offer more land and animals to hunt. Today, landowners in Laikipia and its environs include Guy Wildenstein, a close associate of former French president Nicholas Sarkozy, who owns a 58,000-acre farm; Fauna & Flora International, which owns the 90,000-acre Ol Pejeta Conservancy that previously belonged to the arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi; former Puma CEO Jochen Zeitz, who owns the 50,000-acre Segera Ranch; and Kuki Gallman, who owns the 100,000-acre Ol Ari Nyiro Ranch and whose book, I Dreamed of Africa, is described by its publisher, Penguin, as a “love letter to the magical spirit of Africa.” Then there’s Ian Craig, the charity-minded aristocrat who converted his family’s 62,000-acre cattle ranch into a rhino sanctuary at the peak of the elephant and rhino poaching epidemic of the 1970s. The property was later renamed Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, and it was there that Prince William, whose family made a fortune off colonial plunder, proposed to Kate Middleton in 2010. The Telegraph breathlessly recounted the site of the engagement in high Blixen-ese: “Lying at the foothills of Mount Kenya the ‘rustic and ultra-private’ Rutundu log cabin made a romantic setting for the Prince to pop the big question.”

At the Karen Blixen Museum, our guide Thamima explained to Linda and me that Blixen fought for the right of girls to attend school. She told us about Blixen’s friendship with Berkeley Cole, an Anglo-Irish aristocrat from Ulster and prominent settler-colonialist in Kenya. She also talked about Finch-Hatton, and how his death wrecked Blixen; his grave lies in the Ngong’ Hills.

The house showcases the material artifacts of Blixen’s life in Kenya: the leopard skin on the living room floor; the gun rack, lion skin, and Louis Vutton suitcase in Bror’s bedroom; the bedside table made from the foot of an elephant the two of them hunted; their china, their linen, the table at which they entertained Prince Edward, who was later, briefly, King of England. Some of these items are originals, but others are stand-ins donated by the National Museum. Boots, hats and coats in the wardrobe, as well as aprons in the kitchen, are costume pieces from the movie, worn by Streep and Redford in 1985.

I asked Thamima how it feels, as an African, to talk about a white colonialist all day long. “I enjoy interacting with people,” she told me. “And she wasn’t all bad. We have to take the good.”

In the Western (especially British) imagination, Kenya occupies an outsize place. Writing in The Guardian in 2019, Afua Hirsch observed that Africa is synonymous with Kenya in the “British tourist lexicon.” At the root of this romanticization of the country is Blixen and the blockbuster adaptation of her story, which drew on colonial-era British notions of the African frontier while conveniently erasing the violence of empire, a paradox that saturates safari tourism more broadly. For just a few thousand dollars a night, one can live in the romantic utopia that is Africa, where the spirit of the land will replenish one’s dying spirits.

Tourist brochures of Kenya still describe it as the aristocratic utopia of Blixen’s memory. CNN recommends a list of luxury camps, with the first named after Redford’s movie character: “Finch Hattons is a place for people who have a feel for bygone romance.” In the Mara, the Karen Blixen Camp describes itself as “an eco-friendly luxury camp that gives a sense of the exciting explorer days when the savannah was seldom visited and elaborate and comfortable camps were set up providing a luxurious and stylish retreat after each day’s adventure.”

Then there is Giraffe Manor, a ten-minute drive from the Karen Blixen Museum, which similarly advertises itself as a throwback to Kenya’s colonial past. “With its stately façade, elegant interior, verdant green gardens, sunny terraces and delightful courtyards, guests often remark that it’s like walking into the film Out of Africa,” the website reads. “Indeed, one of its twelve rooms is named after the author Karen Blixen.” Another is named for Finch-Hatton. This “is not a statement about colonization,” insists Julia Perowne, founder and CEO of Perowne International, the London-based agency that handles PR and communication for the Safari Collection, the group of luxury safari destinations of which the Manor is part. Blixen and Finch-Hatton, she assures me, are simply “famous people who everyone in Africa knows.”

A cursory glance at the Giraffe Manor’s ownership offers a crash course in the Karen Cowboy phenomenon. Giraffe Manor is part of the Safari Collection, owned by Tanya and Mikey Carr-Hartley, “fourth-generation Kenyans each with long histories in East Africa,” i.e., their families came to Kenya as part of the British colonial project. According to the masthead provided on the Collection’s website, “Mikey grew up on a 45,000-acre ranch in Laikipia, tracking animals in the footsteps of his grandfather, who was a renowned wildlife handler.” Meanwhile, “Tanya spent her childhood on Loldia Farm on the shores of Lake Naivasha in the Great Rift Valley, helping to manage and conserve the family farm.” The two of them, we are told, “share a mutual love of the Kenyan landscape and its wildlife and have dedicated their lives to protecting it.”

Early in 2020, Giraffe Manor found itself in the eye of a storm when Ahnasa Destinations Ltd, the PR agency handling its affairs in Kenya, announced on Instagram that, due to a catastrophic downturn in overseas tourism brought about by Covid-19, the manor was now accepting Kenyan visitors. In the wake of public anger at the insinuation that the property had not previously been open to Kenyans (among other allegations of racism at the Manor), Ahnasa Destinations hastily deleted its post, and the hotel announced that it had always welcomed everyone, regardless of colour, tribe, religion, sex, or nationality. Yet it is impossible to ignore the fact that the website featuring videos of visitors breakfasting with giraffes and frolicking on the grounds of the manor includes a grand total of zero Black faces. As Perowne told me directly, the manor “wasn’t for everyone.” When I prodded further, she backtracked, saying that the Manor was open to everyone, but that booking two years in advance was required. “Stop looking for something where there is nothing,” she concluded.

Rather like the Irish writer Joyce Cary’s books on Nigeria, Blixen’s work was widely accepted in the U.S. and Europe as an accurate description of Kenya. The film, which has recently been added to Netflix and HBO Max, has ensured that she remains a visible exponent of aristocratic colonial nostalgia.

The final section of Out of Africa sees Blixen lamenting the death of her perfect Kenya. A string of factors — the decimation of wildlife herds by European hunters, increased industrialization and agricultural production by the colonial government, the fact that middle-ranking officers in the British army had been settled in the colony, and the 1929 financial crisis — meant that change was afoot. Unmentioned by Blixen, but also present, were political rebellions by Africans against British colonial rule. A few years later, there would even be armed resistance, close to Nairobi, by the Mau Mau against the British settlers. Blixen, by then, was long gone.

Kenya’s settler class was never again as powerful as the settler class in, say, Zimbabwe, another former British colony in Africa. However, at independence, the country’s governance was seized by a cabal of men who had been in collaboration with the colonial state. Instead of putting an end to the colonial caste system, these men merely sought to join its ranks, which meant, among other things, acquiring houses in posh suburbs like Lavington, Muthaiga, and Karen. In a few years, the Kenyatta family, whose patriarch Jomo was the first president of the Republic, stood alongside old British aristocratic families like the Delamares in the hierarchy of the largest landowners in the country. Meanwhile, the legacy of the settler-colonial class lives on in the Karen Cowboy set and the luxury tourism circuit. The safari, rather than the hunt, has become the dominant mode of viewing Kenya’s wilderness.

In Nairobi, lack of planning means that the best-designed neighborhoods, and hence the locations of the most desirable real estate, are the former colonial suburbs. Driving away from the museum, Linda told me why she likes living in Karen: the quiet; the distance from the city center; the trees and foliage; the large open spaces; the evident planning. All of which is exactly how Karen was sold to prospective residents a hundred years ago. Nostalgia is not the sole purview of the KCs: Linda pointed out some of the newer houses in the suburb, dismissing them as ostentatious, soulless developments.

The uncomfortable fact remains that in Nairobi, alternatives to colonial nostalgia are often unattractive. The developed parts of the city least in thrall to the bygone empire are temples to urban sprawl and thoughtless retailification, represented by suburban megamalls like Two Rivers and Garden City. While Nairobi lays out the blueprint for the tallest building in Africa — entering a four-way fight for continental dominance with South Africa, Morocco, and Egypt — nearly three-quarters of the city’s population live in slums. The colonial, British-built railway from Nairobi to Mombasa has been swapped out for a modern, Chinese-built one — which runs through, and thus degrades, one of the city’s greatest treasures, Nairobi National Park. Meanwhile, new mega-highways are constantly under construction across the city. We have yet to articulate a positive vision of authentic and sustainable Kenyan urban design to match the streets that were renamed after independence. So we continue to be in thrall to Karen — and the Karens — around us.

Karen Blixen wrote, in a letter to her sister, that some people “have the gift of ‘making myths’; their personalities remain alive in people’s consciousness as well as their works.”

As the myth of Blixen and her cohort persists — and continues to shape the landscape and destiny of Kenya and its people — the questions today are, “whose myth?” And “whose country?”

Carey Baraka has written for The Guardian, The New York Review of Books, and A Long House.