Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

In Haaland v. Brackeen, decided this June, Justice Neil Gorsuch’s concurring opinion again reminded readers just how rarely the high court has demonstrated a clear, coherent approach toward federal Indian law. The case focused on the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which was passed in 1978 to reduce the number of Native children removed from their families and to preferentially place Native adoptees and foster youth within their own tribes — this after several centuries of colonial kidnapping and forced assimilation. Gorsuch used his concurrence to do what he does best: give a history lesson laden with thinly veiled jabs toward his colleagues. This time around, the lesson was a reminder that Congress, not state governments, holds the authority to enact and enforce the ICWA. “In adopting the Indian Child Welfare Act,” Gorsuch wrote, “Congress exercised that lawful authority to secure the right of Indian parents to raise their families as they please; the right of Indian children to grow in their culture; and the right of Indian communities to resist fading into the twilight of history.” He then gave this list the ultimate originalist stamp of approval: “All of that is in keeping with the Constitution’s original design.”

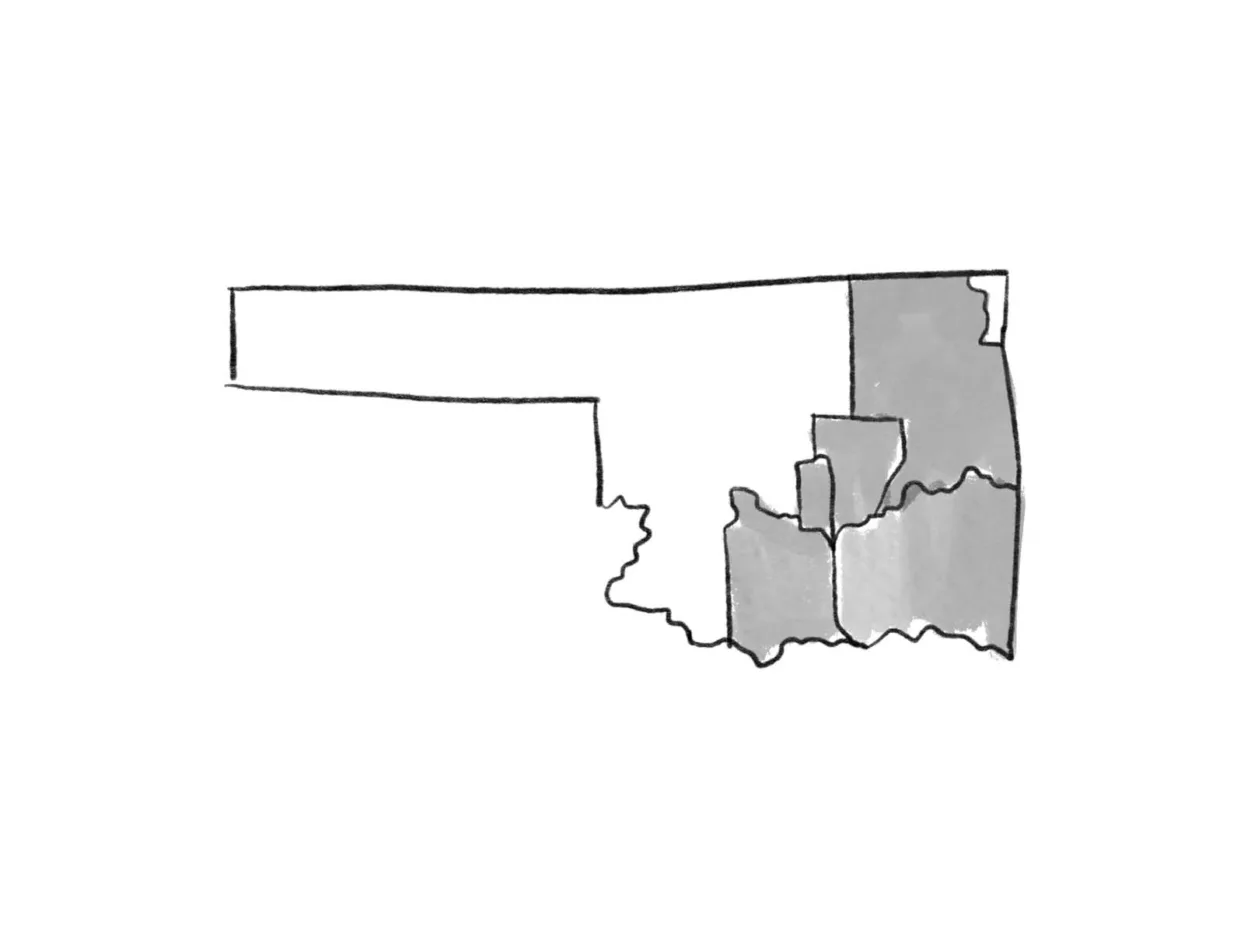

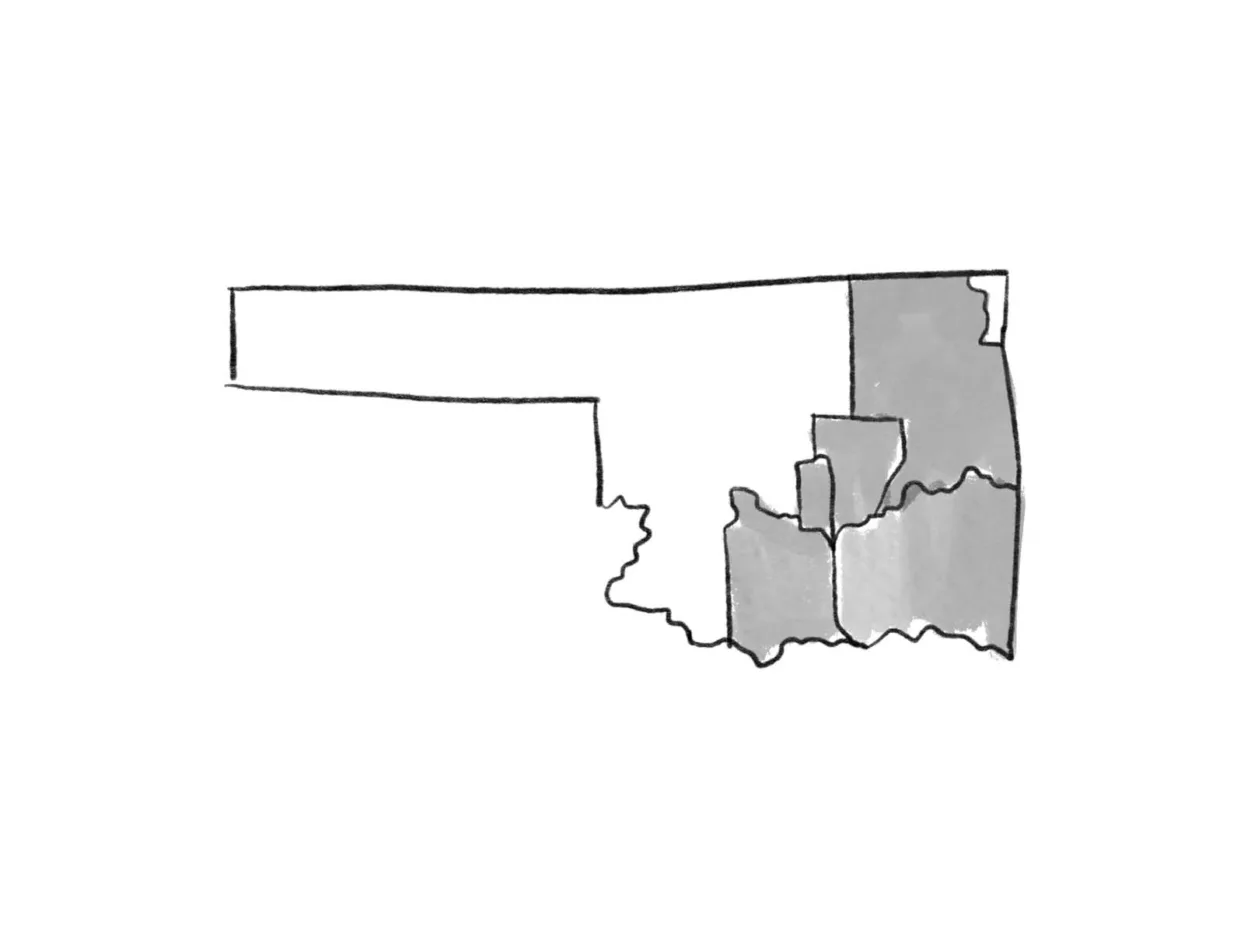

Within Native spaces, Gorsuch is often thrust into the heavens as a near-savior, a robe who finally gets it; outside of these spaces, among liberals, his alignment with tribal citizens and nations mostly makes heads tilt. “Don’t ask me to explain why,” Slate court reporter Mark Joseph Stern tweeted after the ICWA ruling, “but Justice Gorsuch is the strongest and most consistent ally of Native American tribes ever to sit on the Supreme Court.” Expressions of confusion have reliably followed many of his most profound opinions — especially his 5-4 majority ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, from 2020, which determined that nearly half of Oklahoma falls within Indian reservations (a decision nearly neutralized two years later). The New Yorker’s Amy Davidson Sorkin noted that the impact of Gorsuch’s stance, partially shaped by his time on the Tenth Circuit in Colorado, could be seen in the careers of the clerks that pass through his chambers. But for now, on this bench, the impact of Gorsuch’s opinion is largely limited to the emotional reaction it stirs in readers. Folks who are paying attention know that his salvos do not move the needle for the five most important sets of eyeballs — those of his fellow conservative justices. As University of Michigan law professor Matthew Fletcher (Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians) explained to me, “It’s lovely rhetorical fodder,” but “it’s not operative language that could be expected to persuade other judges in the future.”

Gorsuch is not a particularly tough nut to crack; before he goes to bed every night, he tucks in his copy of the Constitution. Treaties just so happen to be a core part of that document — just as much “the supreme Law of the Land” as any constitutional article the founders wrote — and so Gorsuch has made it a mission to ensure that tribal-treaty law is upheld by every court he’s ever sat on. He also voted last year to strip American citizens of their abortion rights and, while on the Tenth Circuit, went to bat for Hobby Lobby over the same issue. Per the majority opinion in Dobbs, which Gorsuch signed onto, “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion.”

Gorsuch’s relative command of Native history will not save Indian Country. Nor will the reelection of Joe Biden or the timely retirement of Sonia Sotomayor. A Biden win, of course, portends a more manageable four years for tribes than a Trump victory, Sotomayor will attempt to protect the long list of civil rights currently in the high court’s sights, and Gorsuch’s prose will continue to be a salve amid the dreck that Clarence Thomas cooks up in closed chambers. But none of this can erase the fact that Kavanaugh, in his own Brackeen concurrence, effectively invited future challenges to ICWA, that Thomas has been openly challenging the very concept of tribal sovereignty in his opinions for the past two decades, or that other decisions made by the Court in the name of constitutionalism will put the lives of Native people at risk. While Native nations, in some instances, can count on their unlikely ally, most tribal governments and their legal branches are doing everything they can to steer clear of the Supreme Court for one simple reason: a federal body built on colonization cannot and will not return real power to the nations it has spent the past two-plus centuries attempting to erase. True Indigenous sovereignty would mean not having to beg another nation’s courts for your rights.

Nick Martin is a member of the Sappony Tribe. He works as a senior editor at National Geographic and was previously the Indigenous Affairs editor at High Country News.