Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

If you are concerned about your children — if you suspect they might be taking their freedoms for granted, or failing to sufficiently appreciate the Great American Experiment — then perhaps the Dissident Project can help. This initiative, founded in 2022 by a Venezuelan-born Columbia graduate student named Daniel Di Martino, offers to bring real-life dissidents to present at your kid’s high school, gratis. Its mission? To inform the youth of today about “how authoritarianism takes hold, what happens when it does, and what America can learn from current and former socialist states around the world.” So says its website, which proposes three different forms of civic courage: BECOME A DISSIDENT / BOOK A DISSIDENT / DONATE. These bookable dissidents, drawn from eight different countries around the world, all preach from firsthand experience that Americans should be grateful and proud, and that authoritarianism and socialism — the terms get used interchangeably — are slippery-slope temptations that must always be resisted. The bio of one Venezuelan dissident, Jorge (Christian, lawyer, freedom fighter), reads, “Living under socialist tyranny showed Jorge the dangers of letting the State grow. From a very young age, he has been speaking out about the very real damages caused by socialism and has made it his life’s mission to win the fight.”

The Dissident Project is sponsored by Young Voices, a talent agency and P.R. firm that represents “a rising generation of heterodox thinkers.” Recently, Di Martino posted an interview in which he explains what the United States means to him. “Every time I walk and I see an American flag on the street, I stop a little bit, and I think: Wow. How lucky, how blessed I am to live in America,” he says. “And I think that every American should feel the same way.” He goes on to quote Ronald Reagan’s speech at the 1980 Republican Convention before finishing on message: “That’s why I started the Dissident Project. So that people from North Korea, from Cuba, from China, from Venezuela, could tell the world that we are a beacon of hope.” But Di Martino’s dissident army isn’t really addressing the world, unless you count me creeping from my laptop in Berlin. What they are doing is telling America that America is a beacon of hope. This is surely a welcome balm for a nation whose self-esteem has been roughed up in the thirty-odd years since defeating the Soviets’ evil empire. As acts of hard-core anti-authoritarianism go, however, gassing up the world’s one superpower on its own soil might leave something to be desired.

Dissidence is having a moment. On the right, especially, self-styled freethinkers are gleefully adopting dissident postures and terminologies. Far-right figures like Richard Spencer get described as “Dissident Right” when they split off from the Republican mainstream; the influential neo-reactionary blogger Curtis Yarvin shared “a speech code for dissidents” with his followers; last year, The New York Sun called anti-woke Substackers like Meghan Daum and Jesse Singal the “dissident left.” The former American Conservative columnist Rod Dreher has also taken up the mantle: his recent book, Live Not by Lies, was subtitled “A Manual for Christian Dissidents,” and he regularly invokes anti-Soviet dissidents in his struggle against the “soft totalitarianism” of America’s left. In his case, that struggle has involved moving to Hungary and writing lengthy newsletters in praise of Viktor Orbán. Pop the word “dissident” into the site formerly known as Twitter (before it was liberated from the yoke of soft totalitarianism) and you will find, alongside reporting on international protests, an article about a neo-Nazi Telegram group called “Dissident Homeschool,” a video in which Robert F. Kennedy Jr. tells Jordan Peterson that podcasts will help “dissident” voices enter the presidential race, and the surprisingly active account of Dissident Soaps, a “based soap merchant” whose products include Mask Off Body Wash, Crusader Body Wash, Ancestor Natural Deodorant, and a bar soap named Caudillo, which comes with Francisco Franco’s face on it. (For just 85 dollars, the “Dissident Megapack” is a perfect gift for the American dad who likes his cleansing both bodily and ethnic.)

The dissident sows confusion whenever he appears — which is increasingly often, particularly since the war in Ukraine returned post-communist Europe to the zeitgeist. “Dissident” remains a go-to term in the Western liberal media for rebellious foreign intellectuals from undemocratic states like China (Liao Yiwu, Ai Weiwei) and the UAE (Ahmed Mansoor), especially when these figures appear at literary festivals such as PEN World Voices, which used to run something called the Dissident Blog. The magazine Dissent published an essay in 2021 praising the avowedly apolitical twentieth-century Czech novelist Bohumil Hrabal, because, though not a dissident himself, he “earned the affection of the dissident movement” in post-1968 Prague. The U.S. reception of contemporary Russian author Vladimir Sorokin has seen the word “dissident” thrown around plenty. In 2022, a New York Times guest essay invoked the history of “high-profile Soviet dissidents and intellectuals” who were “greeted enthusiastically in the United States and Western Europe” during the Cold War to encourage the West to once again welcome Russian “dissidents” — intellectuals who see emigration as “the only remaining avenue for political protest.” Meanwhile, social media users debate whether Russian army deserters are “dissidents” or “cowards.” And when the Wagner militia chief Yevgeny Prigozhin died in a plane crash this summer, the New York Post announced the death of a “Russian dissident.”

In its modern incarnation, the dissident trope relies on the two-bloc worldview of the Cold War, wherein the enemy of our enemy is our freedom-loving friend. We now live, alas, in more complicated times, which can cause embarrassment when dissidents fall short of Western liberal expectations. The New York Times published a guest essay by the North Korean émigré and conservative darling Yeonmi Park — who brings untold panache to the grateful dissident routine, spreading wildly inconsistent tales about how a woman was killed for watching a James Bond movie, how she survived by eating grass, and how the DPRK doesn’t even have the concept of dessert — in 2018; just five years later, the paper ran a defeatist profile of her headlined, “A North Korean Dissident Defects to the American Right,” calling Park “the anti-woke ‘Paris Hilton of North Korea.’” (She warns, in her most recent book, that critical race theory is making the U.S. eerily similar to North Korea.) The Obama administration negotiated for the release of Chinese dissident Chen Guangcheng, who then proceeded to come out as a Donald Trump fan. Jamal Khashoggi became a household name and the subject of a documentary called The Dissident before some pundits criticized his earlier closeness with Saudi royals and his collaboration with a Qatar-backed foundation. Somehow, Western media still seems unable to admire foreign acts of resistance without engaging in cycles of hagiography and censure.

As a cultural touchstone — as a term, a pose, and a mythology — the dissident has become both prominent enough and vague enough to justify shaming unpatriotic teens, palling around with Orbán, and saying North Koreans don’t have sweets. This twentieth-century phantom, wrenched gracelessly out of context, causes geopolitical befuddlement while encouraging a nostalgic, complacent rightward drift. Most people described as dissidents historically have done admirable and interesting things; sadly, the West has packaged them into an empty trope designed to flatter our own self-image and received ideas, rather than considered them as challenging, messy, disobedient individuals with their own ideas. Today’s dissident narratives lay claim to timeless human truths while drawing false historical equivalences. They provide the thrill and reassurance of winning the Cold War all over again — but do more to obscure than resolve our era’s unique challenges. With all due respect to the rebels themselves, it’s time we put the dissident to rest.

Originally used to characterize religious heretics and nonconformists, the term “dissident” — from the Latin for “one who sits apart” — was reincarnated by the Western media in the latter half of the twentieth century as a label for regime-critical intellectuals in the USSR and Central Europe. After the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which laid out a common East-West framework based in human rights and non-aggression, the dissident epithet increasingly became associated with Western discourses around “free speech” and “civil liberties,” ideas supposedly anathema to the region’s so-called totalitarian governments. What has emerged since then is a narrative that vastly under-represents the diversity of disobedient activity and thought in the Eastern Bloc. In reality, these rebel scenes were massively heterogeneous: many individuals dissented against their respective regimes not because they desired capitalist liberalism, of which they were often explicitly critical, but on account of socialist, feminist, environmental, or sometimes even conservative nationalist commitments. Few prominent dissidents had the goal of total regime change, or would have even thought possible the events of 1989 — events that seemed, with hindsight, to vindicate outright regime opposers rather than those who sought improvements within seemingly permanent systems. Yet the character of the Cold War dissident, as he appears in Western commentary today, is remarkably uniform. He is a man, an intellectual, and sometimes an artist, but he is always more interested in ethical imperatives than in airy-fairy aesthetics. No agitator or activist, he’s instead a normal bloke who gets politicized reluctantly; he eschews reform and compromise in order to speak truth to power; and he emulates the U.S. (or sometimes Western Europe) as the only alternative to totalitarian oppression.

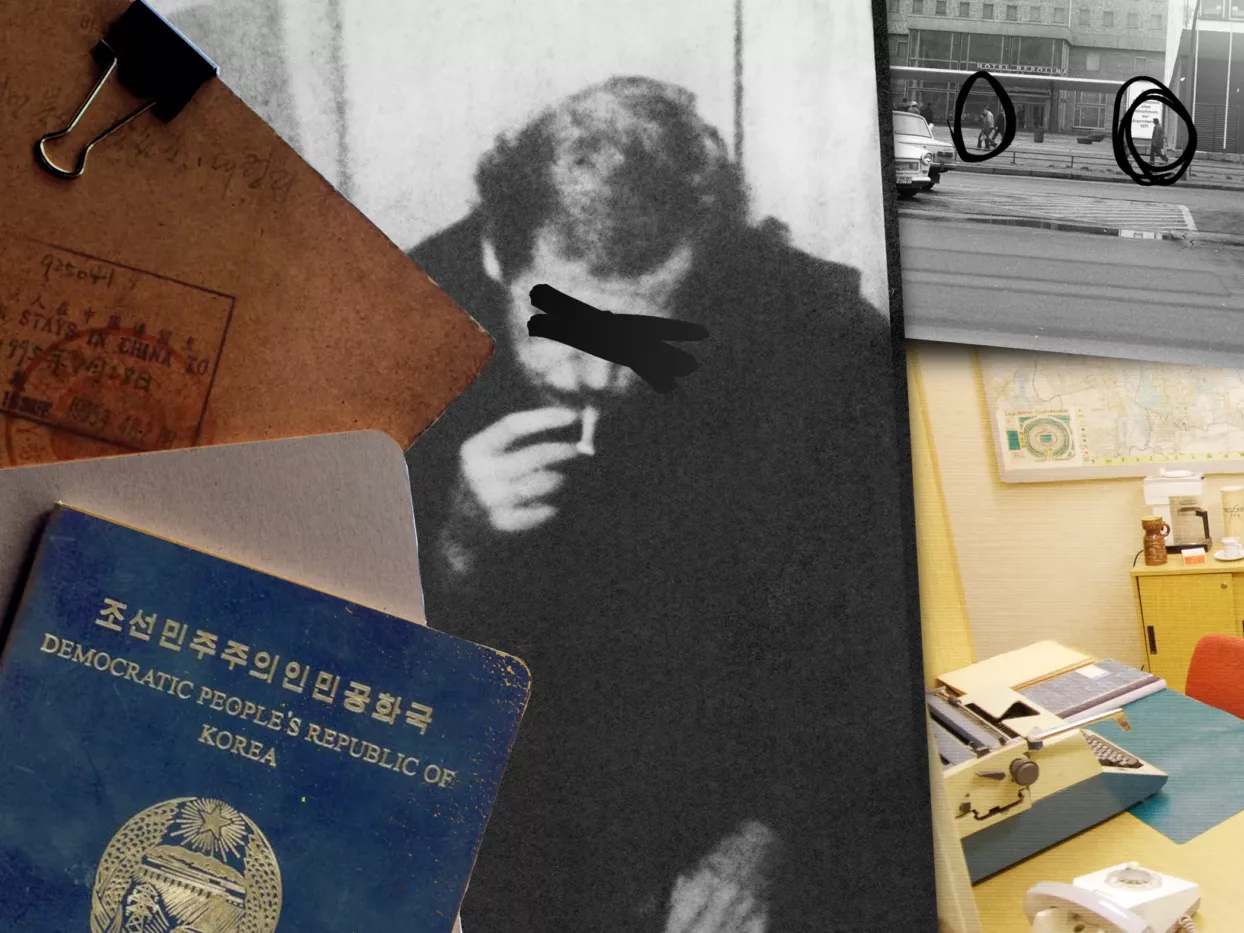

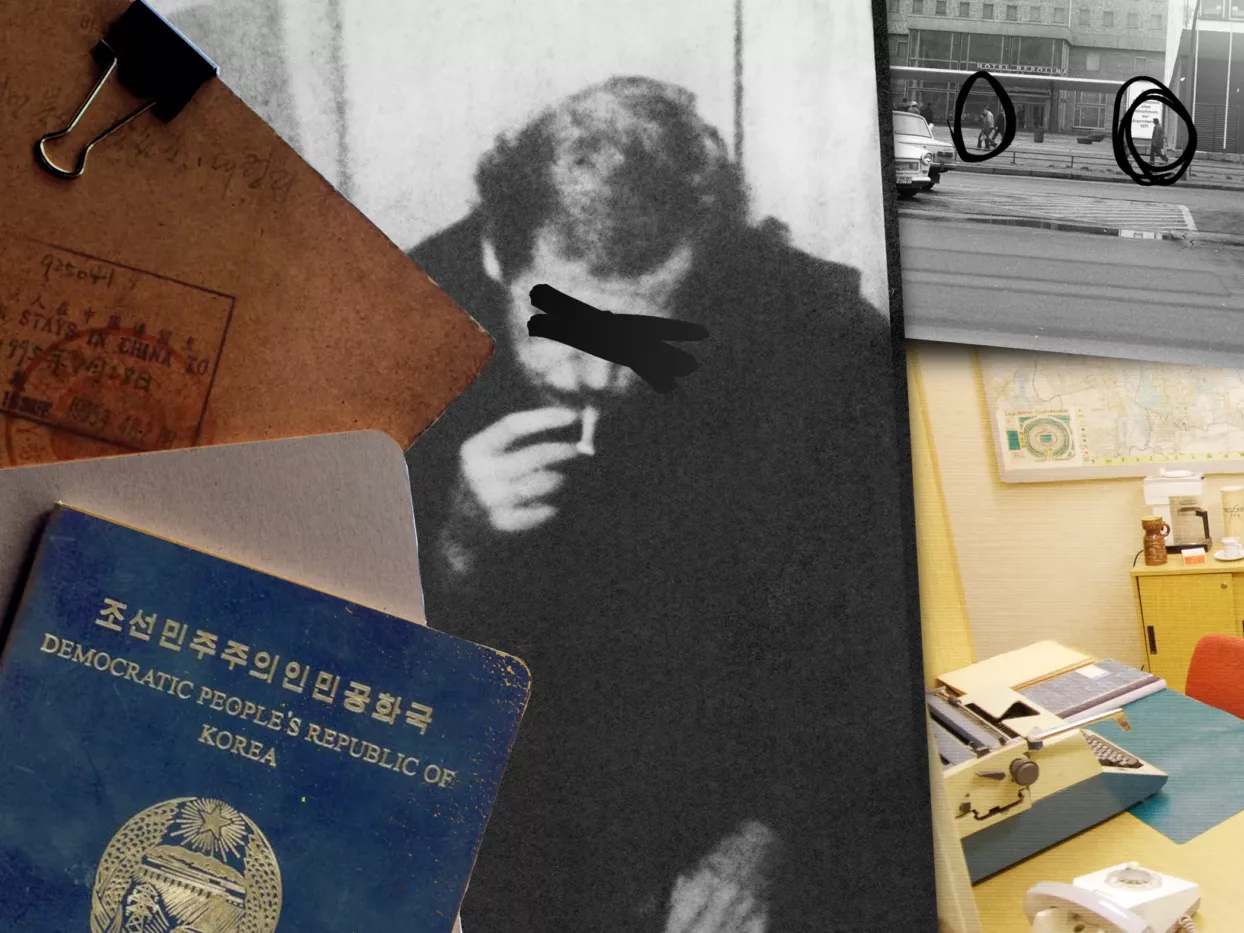

“Dissident” today conjures a medley of romantic twentieth-century images: secret codes and bugged phones and leather jackets and smoke-filled rooms where fingers pound out illicit political texts on aging metal typewriters. The dissident as we imagine him is a cliched composite of people like the Soviet author Osip Mandelstam (arrested in 1934 for reciting an anti-Stalin poem), the Polish rebel Adam Michnik, the Hungarian novelist György Konrád, and especially the Czech playwright-philosopher Václav Havel, who ascended from Prague’s disobedient 1970s cultural scene through periods of imprisonment and police harassment to become his nation’s first post-communist president. Above all, the modern dissident figure descends from the Russian author Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who earned worldwide renown for his account of Soviet imprisonment in The Gulag Archipelago, before moving to America and becoming an icon of resistance and a maverick conservative intellectual. Solzhenitsyn, who returned to Russia in the ’90s and died in 2008, remains the most prominent and problematic dissident. Each new Gulag Archipelago anniversary summons debates about his legacy: most commentators point to his heroic anti-Stalinism and brilliant creative-nonfictioning, while others counter with his anti-Semitic language and seemingly unreconstructed Christian nationalism, not to mention Putin’s apparent admiration for him — as if all this couldn’t possibly coexist. Solzhenitsyn long seems to have held a permanent moral-authority pass in the West based on his courageous opposition to the gulag. But hating the gulag does not actually tell us much about somebody’s politics or ethics. It’s the gulag — you’re supposed to hate it!

The twentieth-century individuals labeled as dissidents were often skeptical of the West’s mythologies about them, as the historian Jonathan Bolton notes in his study of Prague’s cultural underground. Yet they understood that support from the Western media could offer a degree of protection from state oppression, boost potential overseas book sales, prompt invitations to appear at literary festivals, and lead to other career opportunities should one ultimately decide to emigrate (or, in the dissident lingo, “defect”). Supporters in the West could also help pressure communist regimes to lighten up on disobedient intellectuals, especially in the post-Helsinki period, when the Cold War’s two blocs were more diplomatically and economically integrated than many like to admit. Over time, the narratives around them became homogeneous and unchallenging, and above all centered on individual anti-communist heroes. From the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn and the physicist and Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist Andrei Sakharov became the headline dissidents, with the latter — for instance — celebrated by a book of tributes in 1982, reviewed in a New York Times article (headline: “The Dissidents’ Dissident”) that noted Sakharov’s “direct and concrete defense of individual human rights.” Bolton observes that for Czechoslovakian dissenters, Western-style human rights discourse was less a new spiritual lodestar than an international “Esperanto of resistance” with a “ready-made audience abroad,” far more marketable on the global stage than some of the Protestant-existentialist, absurdist-surrealist, or literary-gossipy material that circulated in Czechoslovakia’s samizdat magazines. In matters of dissent, as Bolton writes, the Cold War West “often thought it was listening in on a conversation that, in fact, it had helped to stage.”

For both practical and ideological reasons, most popular accounts of life “behind the Iron Curtain” came from a highly unrepresentative (and unrepresentatively West-friendly) sector of society — an oppositional intelligentsia comprising, firstly, emigrants whose anti-communist politics secured them jobs at American think tanks and universities, and secondly, writers in major cities like Prague and East Berlin who had Western contacts and knew how to present an appealing narrative. Above all, that narrative meant posing as the capital-D Dissident, a character who was primarily, as Bolton argues, the invention of Western journalists. Even Havel himself only really identified as a dissident “in quotation marks,” as he put it, resisting the term for years before finally accepting it as a strategic necessity; his famous political essay about the ethics of resistance, “Power of the Powerless,” begins by wryly declaring that “a specter, which in the West is called ‘Dissidence,’ is currently haunting eastern Europe.” In that essay — which, among other things, theorizes resistance to the regime as something not restricted to a clique of intellectuals — Havel registers his discontent with the “dissident” tag, noting that the term is typically only applied to writerly people who express their nonconformist views systematically before a Western audience, who have a level of prestige that protects them from the worst persecution, whose politics engage “general causes” beyond their local situations, and who are admired abroad primarily as activists rather than for whatever they do for their job. (Havel was cross that Westerners saw him as a political figure, not a playwright.) In 1981, after being asked by a Western journalist, the regime-critical Soviet author Vladimir Voinovich penned an op-ed for The New York Times entitled “I Am Not A Dissident.” Yet foreign commentators often proved reluctant to relinquish the dissident scripts that they packed with them on trips east. The Czech-born British playwright Tom Stoppard’s 2006 play Rock ’n’ Roll includes a scene in which a friend of the underground rock band The Plastic People of the Universe — then in the midst of being publicly prosecuted by the Czechoslovakian authorities — tells a visiting British reporter that “the Plastic People is not about dissidents,” to which the reporter replies: “It’s about dissidents. Trust me.”

After 1989, the selective process around dissident stories became supercharged. Western portrayals — and invocations — of anti-communist rebels, even famous ones like Havel, became increasingly devoid of almost all the content of those figures’ thought beyond a morally obvious opposition to tyranny and a vague commitment to freedom and truth. In one essay from the 1990s, Czech author Ivan Klíma describes a fictionalized encounter with a foreign journalist, a composite of reporters he had previously met. Despite his request to talk about literature, not politics, the journalist insists on quizzing him on current affairs, then asks him what he is going to write about now; since totalitarianism was over, she helpfully points out, he must be lacking in material.

By the 21st century, the dissident trope had become seriously unmoored from Cold War realities, providing, instead, a series of self-flattering fantasies against a nightmarish foreign backdrop. One of its purest articulations came with the U.S.-based West German director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 film The Lives of Others. This Oscar-winning melodrama follows East Berlin playwright Georg Dreyman, a golden boy of the 1980s GDR. Early on, a Stasi chief calls him “cleaner than clean” and says, “If every author was like him, I wouldn’t have a job.” But then Dreyman finds out his pill-addicted girlfriend is being coerced into sex by the culture minister, and a director friend blacklisted by the regime commits suicide. As the film reaches its climax, Dreyman decides to finally do something. Enough is enough! So Dreyman writes an article for the West German magazine Der Spiegel slamming East Germany for not publishing suicide statistics and implying that the state had hidden a spike in suicides caused by its own repressive policies. The movie is set in 1984; by then, the West German press was making similarly dramatic criticisms of the GDR. In the film, though, Dreyman’s article is a scandal. His girlfriend dies in the ensuing Stasi action, but Dreyman becomes a hero. (The Stasi officer assigned to surveil him also turns good, inspired by the soul-saving experience of observing a dissident.) The Wall comes down within five years, and in post-reunification Berlin, the righteous receive their rewards: Dreyman writes a best-selling book dedicated to the former Stasi man, who sees it in a bookstore window and buys himself a copy, deeply moved.

But what makes Georg Dreyman heroic? The fact that despite years of complying with the state, ignoring reform movements led by East German intellectuals, and whatever else keeps you “cleaner than clean,” he at last decided to write, in the anti-communist West German press, that the GDR stinks, thus achieving nothing but the death of his girlfriend? (Look, mate, we all want a clip in Der Spiegel…) Donnersmarck is, among other things, a master of packaging German history into cliches fit for export: The Lives of Others dresses its Stasi like Nazis; it presents high art as dynamite against historical evil, and mass surveillance as an exclusively East German problem; and it announces its allegiance to international resistance kitsch through references to Solzhenitsyn and Orwell. Above all, with Dreyman’s nonsensical hero arc, the film deploys the West’s beloved and reassuring stereotype of artistic resistance.

In the real East Berlin of the 1980s, courage and commitment took a vast range of forms. There were avant-garde poets and intersectional feminists, political activists and underground priests, peaceniks and punks and standard-issue dropouts. But Donnersmarck’s Dreyman is hunky, proud, and happily apolitical until the state invades his private life. (While the most interesting dissenters were largely women and, according to Slavoj Zizek, almost all known cases of intra-marriage betrayal involved husbands reporting on wives, Dreyman is let down by an inconstant woman.) Moreover, Dreyman’s supposed dissent is clearly not ideological; it’s simply personal. At one point, Dreyman turns to his girlfriend and says, “You know what Lenin said about Beethoven’s Appassionata? ‘If I keep listening to it, I won’t finish the revolution.’” Indeed: The Lives of Others is a tale not about political awakening, but its opposite: from the fog of socialist ideology, Dreyman becomes a straightforwardly truth-speaking dissident, while the repentant Stasi officer gets reborn as a self-respecting pro-art individual. Donnersmarck — who once told The New Yorker that his aristocratic German family was “too cultured to have been Nazis” — conjures a film in which art is not just healing, but true, and true in a way that precludes any ideology except individualism. Little wonder it has been criticized by basically every Eastern German I have ever met, but praised by the conservative Western German press, GDR dissidents turned far-right agitators like Vera Lengsfeld, and American right-wingers like William F. Buckley Jr., who called it “the best movie I ever saw.”

As the film makes clear, the dissident narrative relies on a version of twentieth-century history in which, under a totalitarian regime, truth is utterly anathema to power. The so-called “totalitarian hypothesis” — which equates communism and fascism as entirely totalizing illiberal power structures that police all art and thought — does not accurately describe the late Cold War Eastern Bloc. As the American historian Samuel Clowes Huneke has written, the image of East Germany as a totalitarian state on par with the Nazi regime is “simply wrong.” The GDR did not realistically aspire to total control over the public, private, and internal lives of its citizens, nor did it ever achieve it; the deployment of terror, surveillance, and the threat of violence was certainly appalling, but can’t compare in scale to that of the Third Reich. (Some 140 people were killed at the Berlin Wall; six million Jews were murdered by the Nazis.) The state sought legitimacy, rather than simply demanding it at gunpoint, often making major compromises to placate activist movements and citizens’ initiatives. “Niches” of private life and informal association undermined the totalitarian model’s claim of total state regulation. Solzhenitsyn himself reflected that “dissent” in the later Soviet years held far fewer risks than it did under Stalin.

The supposedly inevitable dichotomy between truth and power is — like the dissident — a Western invention, one that conveniently makes us “truth” and anyone we don’t like “power.” And thus, we too can pose as dissidents when we stand against power in our own societies. Indeed, it is easy enough to recognize the specter of the dissident in some of the sillier forms of politicized culture that took root in the Trump era. In 2017, I attended a PEN panel in Brooklyn called “PEN vs. Sword: Satire vs. the State,” which featured the Djiboutian novelist Abdourahman Waberi alongside TV humorist Mo Rocca, among others. The American moderator Elissa Schappell kept boasting that Spy magazine, where she once worked, was the first to call Trump a “short-fingered vulgarian.” These days, it is appealing for intellectuals of all political stripes to see speaking out as an imprimatur of anti-authoritarianism. But if the essential effectiveness of “truth to power” was dubious in the 1980s, it is far more dubious now. Dissidentery lets everyone identify as a brave political agent, even if they haven’t stopped to consider what might make something a genuinely effective utterance or action, as opposed to simply a way of blowing off steam. For #resistance liberals and leftists alike, it lets the giddy thrill of rebellious gesture take the place of strategy. We feel we know, and speak, the truth: but is power really listening?

One of the many intellectual crises faced by the Western liberal establishment today is the fact that its authoritarian enemies seem, unlike Hitler and Stalin, to have sprung from, or at least been encouraged by, the West itself. This is particularly apparent in Central and Eastern Europe, where the rise of populist authoritarianism has often been led by former historical dissidents, and therefore presumed allies of Western liberalism. When he was in his twenties and still forming a political vision, Orbán was welcomed to Oxford and invited on a tour of the U.S.; the U.K. sold its football clubs and prime real estate to oligarchs; our sportswriters had a surprisingly nice time at the Sochi Olympics. The West advocated economic shock therapy in post-communist Europe, we normalized variously ethnic forms of nationalism, and we sent in management consultants and think tanks and transitional advisors to establish the conditions for liberal democracy how we like it, all while celebrating and uplifting those locals we judged sufficiently anti-communist to be part of the post-Wall order. We bet on Wandel durch Handel — change through trade. We gushed about our heroes, Reagan and Bush, but then we got furious when, once in power, post-communist politicians started ganging up on minorities and neglecting the rule of law. Could the rise of authoritarianism in Europe be an “us” problem, too? In hindsight, it seems obvious that the enemies of last century’s enemies would not all prove lifelong friends: there were all kinds of reasons, after all, to oppose the violent rusting wreck that was 1980s European communism, and as the historian Nicholas Mulder has observed, the likes of Orbán have espoused illiberal beliefs for longer than we like to admit.

During the Trump presidency and then the war in Ukraine, we’ve seen the emergence of a coterie of liberal thinkers — such as the fascism philosopher Jason Stanley, the democracy enthusiast Yascha Mounk, and the pro-Ukraine historian Timothy Snyder — who draw on Europe’s twentieth century, especially German fascism and Soviet Communism, to make prescriptions for the present. Instead of facing Europe’s current authoritarianism head-on, liberal and liberal-conservative establishment voices have advocated a return to the moral binaries of the Cold War, prescribing the ailing contemporary West not more equality, inclusiveness, or self-reflection, but instead more boisterous confidence in its global role. This is the project of Anne Applebaum, the Atlantic columnist, Europe watcher, dissident fan, and historian of the Stalin-era USSR whose celebrity status has been boosted by the recent expansion of the war in Ukraine. A Pulitzer Prize winner and senior fellow at Johns Hopkins, she was also invited to testify before Congress last year as part of a briefing titled “Bolstering Democracy in the Age of Rising Authoritarianism.” Applebaum was 25 when the Wall fell, and regularly cites her youthful experiences behind the Iron Curtain — including courier-ing money to dissidents on behalf of the conservative British scholar Roger Scruton — as a source of legitimacy. Her 2020 bestseller Twilight of Democracy, which regularly invokes the legacy of dissidents and their Western supporters, was an extended attempt to frame the far-right trajectory of her former friends, colleagues, and party guests — people like Orbán’s head culture warrior Mária Schmidt and the anti-Semitic Polish journalist Anita Gargas — in terms of individual betrayal, rather than admitting how much they all once had in common. In an Atlantic article from the same year calling on Republicans to break ranks with Trump, she compared Mitt Romney to the East German dissident Wolfgang Leonhard, and Lindsey Graham to Stasi spymaster Markus Wolf. Conservatives, she noted, were becoming likewise “forced to accept an alien ideology or a set of values that are in sharp conflict with their own.” (Throughout her writing, she describes Trump’s election as a watershed moment, the first time Americans were called upon to accept or deny the brazen lies of those in power — but what about those weapons of mass destruction?) In 2021, quoting from a pro-“civil discourse” open letter, she tweeted: “Dissidents from around the world call on Americans to defend democracy — for their sake and ours: ‘if the world’s leading democracy doesn’t believe in its own values, why should dictators even bother paying lip service to them?’”

For the likes of Applebaum and Snyder, twentieth-century history — including the moral example of dissidents — provides a shot in the arm to Western moral confidence in the present wartime context. And how could you dispute that Putin is awful, or that the Ukrainians are right to resist him? It is precisely under the cover of the war’s moral obviousness that neo-Cold Warriors have been able to ply their secondhand intellectual wares. Where the dissident appears, hawkishness is sure to follow. “As long as Russia is ruled by Putin,” Applebaum wrote in The Atlantic last year, “then Russia is at war with us too. So are Belarus, North Korea, Venezuela, Iran, Nicaragua, Hungary, and potentially many others.” During the Cold War itself, many actual dissenters preferred détente to Reagan’s increasingly incendiary rhetoric; certainly his propensity to fund the enemies of America’s enemies, most notably in Central America and Afghanistan, has not served foreign freedom-lovers particularly well. Since 1989, however, dissident talk has primarily served to promote chauvinism and uncompromising lines against ideological foes. In 1999, the Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen defended the love of Reagan among their parents’ generation like this: “He knew the fundamental difference between a normal country and an evil one, and he wasn’t afraid to name it. In this way, he acted like the dissidents: he spoke The Truth, consequences be damned.” Gessen then could not resist projecting this moral certitude into the present: “If George Bush II comes into office and says, ‘Fuck the Chinese and all their stupid cheap goods and their nuclear arms if they don’t know how to do democracy,’ the left and the liberals will jump at the chance of labeling him an ignoramus yet again, but the Chinese dissidents will declare him God. And they, the dissidents, will be right.” Dissidence lends sentimental ballast to the world-police impulse: if dissidents want what we have, then every war we fight becomes a war of liberation. As it turns out, Bush did indeed decide to attack a foreign dictatorship, consequences be damned — a decision Applebaum supported — but Iraqis have not, at time of writing, yet declared him God.

It has become popular to announce that we are living through “a new Cold War” — even The New Yorker is saying so, per a recent headline — that just so happens to have the same villain as the last one. The Russian dissident Vladimir Osechkin was recently quoted saying that Putin has “decided to become the new Stalin”; the former GDR dissident Wolf Biermann called Putin “the legitimate son of the Hitler-Stalin marriage.” Western media has instinctively painted all the world’s dictators in alliance, as if illiberalism were, like communism, a global ideology in its own right. (“The Autocrats Are Winning,” the Washington Examiner declared this year.) But then what do you do with the legacy of Solzhenitsyn, that definitive anti-Stalinist greatly admired by the fellow Christian nationalist currently stinking up the Kremlin? And what about the once anti-Soviet Orbán, who has been Putin’s most enthusiastic apologist inside the European Union?

In search of a Havel for contemporary Russia — a figure we can both encourage in rebellion and also trust, once helped into power, to bring the nation into the liberal world order — American commentators have generally settled on Alexei Navalny. An immensely courageous critic of Putin, Navalny also happens to have made xenophobic remarks about Muslims, called for the expulsion of Georgians from Russia during the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, and unnerved and infuriated many in Ukraine with his reluctance to disavow Russian claims to territory in Crimea. As a critic of Putin who isn’t quite a friend to Ukraine, Navalny seems to jam the dissident logic most spectacularly. In 2021, Amnesty International struck him from their “prisoners of conscience” after an outcry, then reinstated him after a different outcry. PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel pointed out, in response, that the cycle of adulation then disavowal — rather than simply condemning the mistreatment — plays straight into authoritarians’ hands.

After the eponymous documentary Navalny won an Oscar earlier this year, the mayor of Lviv tweeted, “Navalny is a sandwich packed in a lunchbox and carried around the world as an example of the fact that there is still opposition in Russia.” Western observers, trained as we are in two-bloc thinking, have often expressed surprise about such discord. One headline in The Bulwark asked, “Why would Ukrainian patriots feud with Russian Dissidents?” When international publishers released an incriminating insider account by a different so-called dissident, the former Russian soldier Pavel Filatyev, it triggered accusations that Filatyev participated in war crimes, and that he seemed more appalled by Russian incompetence than Ukrainian suffering — especially fierce criticism came from Ukrainians. Earlier this year, PEN America canceled an event involving “Russian Dissident writers” after two Ukrainian authors threatened a festival boycott; the ensuing brouhaha saw Masha Gessen resign as the organization’s vice president and Yascha Mounk get hot and bothered about cancel culture (imagine!). So whom should we side with — the Ukrainians or the dissidents? The answer, of course, is that the question is stupid. Decisions based in strategic analysis and human empathy require no such civilizational profession of faith. If Westerners put the dissident trope to bed, then perhaps we can come to those resisting Putin with less of our own baggage and neediness.

When the dissident is deployed on the home front today, results prove either bafflingly generic or pugnaciously anti-progressive. The former seems to apply best to PEN, which does admirable work supporting imprisoned authors worldwide but gets its wires crossed when bringing its message to American soil: its 2023 gala honored Salman Rushdie and (in absentia) the imprisoned Iranian writer-activist Narges Mohammadi, alongside — naturally — the equivalent champion of free speech, Lorne Michaels. (Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos, slated to receive the PEN America Business Visionary Award, pulled out because of WGA strike action against him.) Resistance against foreign regimes, SNL at home. What will you write about now, Mr. Klíma?

Bari Weiss, an avowedly “centrist” intellectual who has shifted increasingly rightwards, represents the more aggressive flavor of anti-progressive dissident-talk. Since quitting the New York Times editorial desk in 2020 — a move she blamed on the paper’s culture of left-wing intolerance and “self–censorship” — Weiss has referred to “dissidents in a democracy, practicing doublespeak” and compared students’ “parroting” woke beliefs to please their schoolteachers to “a phenomenon from the Soviet Union.” Her list of “ten ways to fight back against woke culture,”published in the New York Post, opened with an extended riff on dictatorship in our times, illustrated by the emails she has received from fans: “They admit to regularly censoring themselves at work and with friends; succumbing to social pressure to tweet the right hashtag; to parroting slogans they do not believe to protect their livelihoods, like the greengrocer in Havel’s famous essay ‘The Power of the Powerless.’”

At the end of a recent interview with Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky, Weiss offered a tip for further reading: to understand the “creeping totalitarianism in this country and how to resist it,” check out a recent book by Dreher — yes, the Orbán bloke. Weiss and Dreher are joined, as contemporary American Solzhenitsynites, by the likes of Jordan Peterson — who penned the foreword to the recent Vintage U.K. edition of Gulag Archipelago — and Daniel J. Mahoney, co-editor of The Solzhenitsyn Reader, who, in a recent interview about the lessons of totalitarianism, compared “the woke” to Nazis and communists, before adding that Paris-1968 was stopping us all from admitting that black single motherhood in the U.S. was caused less by “crimes of slavery” and more by “pathologies of the inner city.” (Among Solzhenitsyn’s literal heirs, one son blurbed Dreher’s book; another has been treading the East-West border zones as a senior partner at McKinsey, heading the firm’s Moscow office until recently.) If Solzhenitsyn’s modern-day acolytes know they must speak truth to power, then what they see as totalitarianism is more than word-policing from the left. “Never lie,” Mahoney said in the same interview, invoking Solzhenitsyn as a model: “Do not repeat slogans. Don’t talk about systemic racism, if you don’t believe it. Don’t contribute to the reigning superstitions. We have to show courage.”

In the hands of people like Donnersmarck, Applebaum, Dreher, and Weiss, the dissident becomes an unideological, even anti-ideological entity: someone simply being decent, refusing jargon, marshaling obvious truths against tyrannical loonies. These narratives turn love of America — of its conservative liberalism, its capitalist democracy, its exceptional global role — into something self-evident and true, while all critique takes the status of foreign ideology. (In a pair of rapidly escalating insults, Weiss once called cancel culture “wrong and un-American.”) This trick is mirrored in the right’s efforts to tar progressive movements with jargony buzzwords like “wokism” and “critical race theory.” Westerners are encouraged to admire our institutions in the abstract while resisting any attempt to make them safer, more inclusive, or more sustainable. What gets normalized is American-style individualism, free-market radicalism, and more or less ethnic nationalism: exactly the sort of thing we’ve spent thirty years telling post-communist Europe to regard not as an ideology, but rather as the natural state of things — what Fukuyama called “discoveries about the nature of man as man.”

At home, the dissident paves the way for anti-wokeness; abroad, he helps bolster fantasies of global dominance while suggesting democracy needs nothing more than defense against its foes. He offers us license to switch off our brains entirely. In the name of courage, we put on a dissident show — but it is a hymn to ourselves, written and conducted by us, one that summons nothing more ambitious than complacency.

Recently, the Dissident Project published a blog post entitled “Dissident Assimilation.” Here, an American college student, Charlie Andrews, recorded his impressions from interviews with the Eritrean dissident Angesom Teklu and the Iranian dissident Tahmineh Dehbozorgi. Previously, he admits, he could sympathize with “complaints in the media” about America today. But hearing these dissidents’ stories helped him see the light. Andrews’s conclusion is one that should warm the hearts of worried parents across the nation: “Concerns about student loans and healthcare prices are legitimate — I have them myself. But our dissidents’ life stories demonstrate that freedom is more important than free things, and the liberty we have as Americans is all we need to succeed.”

Alexander Wells is a critic and essayist living in Berlin.