Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

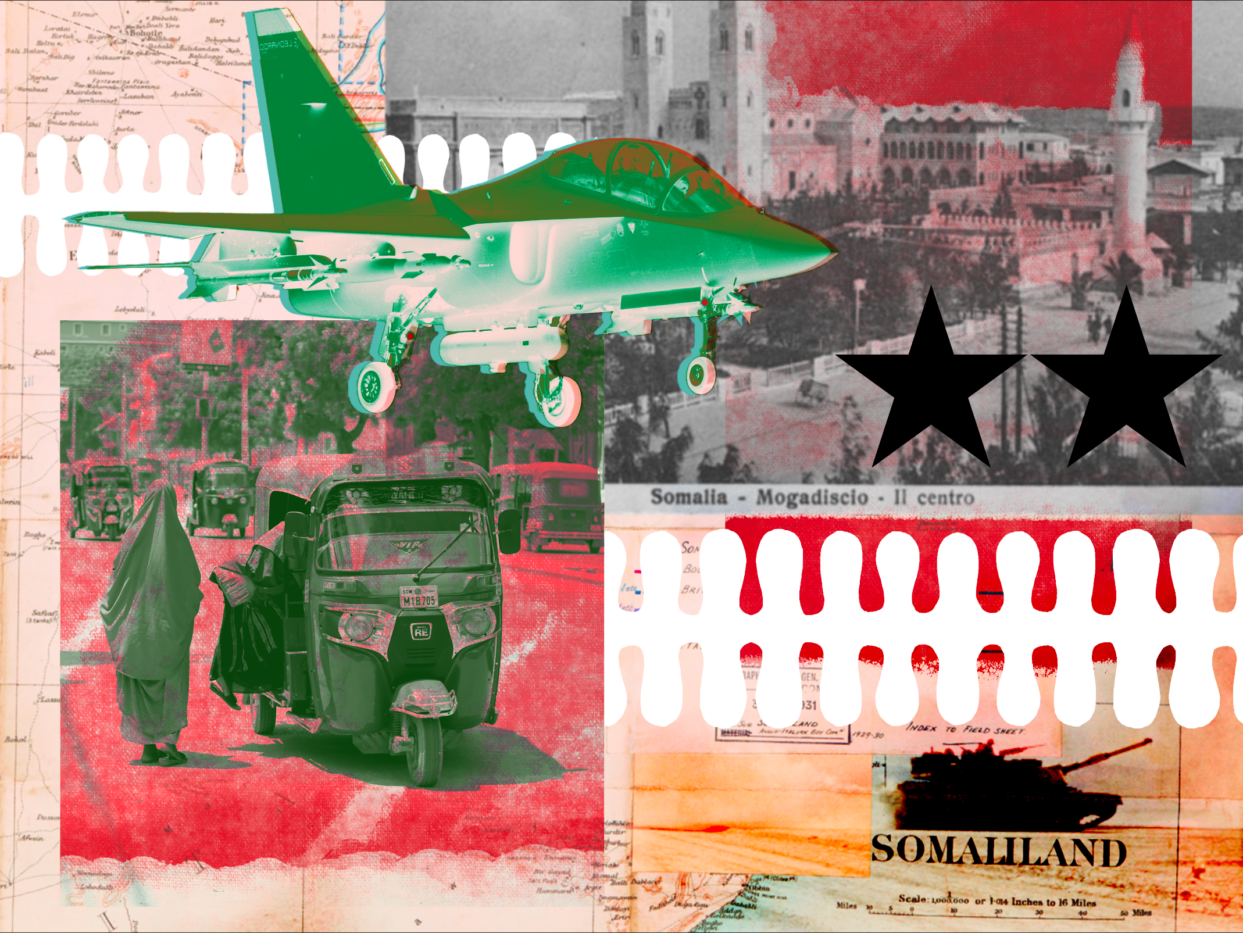

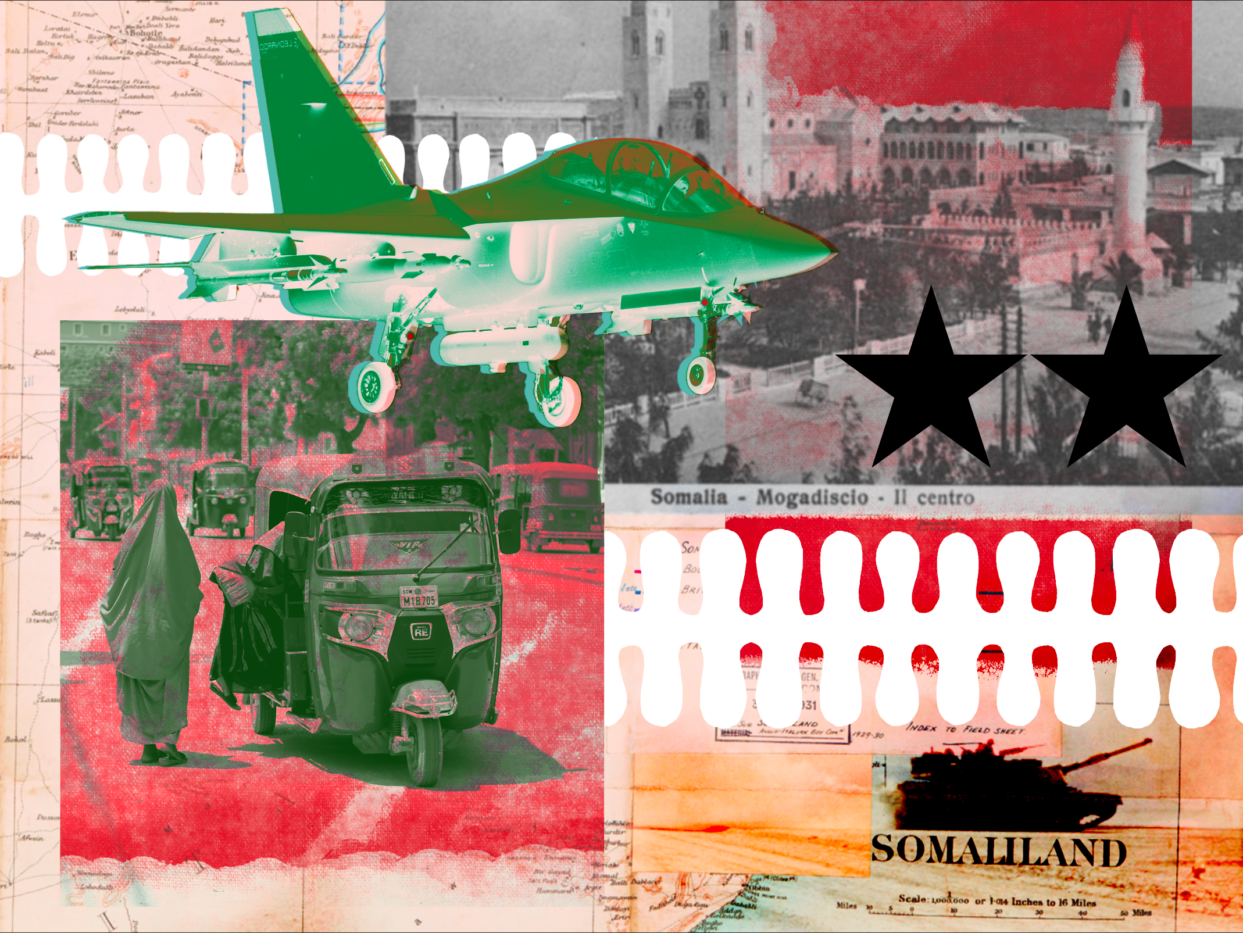

“Italian language teaching is back in Somalia!” the Italian embassy in Somalia tweeted in late September 2021, announcing a new program at the Somali National University that would reintroduce the language of the country’s former colonizer. “Learning a new language,” the tweet continued in shaky English, “means opening your mind and seize unexpected opportunities.” For days, it was ridiculed and meme-d across social media by young Somalis. Why, some wondered, was a colonial language being taught to Somali youth a half-century after independence? What was the Italian embassy trying to accomplish?

Other Somalis, particularly from older generations — people nostalgic for the days of Italophone Somalia, before the chaos of civil war — rushed to defend the program, extolling the virtues of the Italian language and its potential benefits and uses. Collective memory after a conflict is a strange thing. War shatters the collective and reconfigures the memories. Exile inspires alternating bouts of nostalgia and resentment. The ruins that result from armed conflict become symbols of a bygone golden era. The violence of the past appears softer amid the seeming barbarism of the present. Even colonialism, with its myths of order and civilization, can look less heinous in hindsight.

Italy is hardly the most well-remembered of the European imperialists (it has its own history of being dominated by the more infamous colonizers) but its empire was at one time the third largest in Africa. Following its defeat in the Second World War, Italy was forced to give up its colonies: Libya was occupied by the Allies until 1951; Eritrea was administered by the British until, in 1950, it was federated with Ethiopia, where Emperor Haile Selassie’s sovereignty had been restored several years earlier. Somalia was the lone exception. Though the nation officially became independent in 1960, until the 1990s, it remained the last bastion of Italian culture on the African continent. Italians and Italian-speaking people could walk the streets of large parts of southern Somalia, or the area that was formerly Somalia Italiana, without feeling much removed from Italianità. Symbols of Italian culture, from the architecture to the cuisine, could be found everywhere, and especially in the capital city, Mogadiscio. But then the Somali civil war erupted, and everything changed.

The violence arrived in the capital in 1990. By January of the following year, the central state had collapsed, thousands of people had been killed, and many more were displaced to refugee camps in neighboring countries. Since then, the story of Somalia in the global imagination has been frozen in perpetual conflict: violence, famine, Black Hawk Down, failed interventions, the War on Terror, piracy, and on and on. For many Somalis of my generation, born after the war began, the image of Somalia as an ever-churning cauldron vies with a narrative in which the nation is perpetually rising from the ashes.

In the mid-1990s, when Italian troops withdrew with the rest of the United Nations peacekeeping forces that had been deployed during the civil war, the former colonizer seemed to have abandoned Somalia for good — and vice versa. In the transformation of Mogadiscio (now Mogadishu) that resulted from the conflict, all markers of Italian culture were scrubbed. The colonial-era buildings were destroyed in the fighting; more gradually, Italian ceased to be the lingua franca among Somalia’s educated elites. The war, some have argued, completed the long decolonization process by finally breaking Somalia’s cultural, political, and economic ties with Italy.

But decolonization is not as simple as removing surface-level symbols of a colonizer’s culture. And the process does not end when a country gains legal independence. Around the world, imperial relationships have been repackaged and sold as benevolence, as aid, as cultural exchange, and, crucially, as so-called capacity-building programs — training opportunities that are supposed to help citizens of postcolonial states to help themselves. Italian language classes in Somalia are part of one such program, and seem innocuous enough until you learn that Italy’s leading defense company is working hard to promote the rehabilitation of the Italian language in Somalia, with the explicit intention of reviving the country’s imperial-era network of influence in Africa and the Middle East. And if Somalia’s history is any indication, capacity-building will only serve to build, or rebuild, a capacity for dependence.

For the first few years after the Kingdom of Italy was founded in 1861, imperialist projects abroad seemed antithetical to the spirit of the Risorgimento, the revolutionary liberation and unification movement during which Italians fought off Austrian domination on the new state’s own peninsula. But soon enough, politicians and business leaders began to view colonialism as a compelling way to cement Italy’s reputation as a legitimate European power. Their moral messaging refuted charges of hypocrisy with a familiar logic: Italy had a duty to spread its culture and ideals to “uncivilized” peoples. As Minister of Foreign Affairs Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, who had once written that every nation had an inherent right to statehood, argued at the time, maintaining colonies was “just as legitimate in international society as the relationship that is called tutelage is legitimate in private law.” He insisted that tutelage, an ancient Roman legal concept that allowed for the control of “those who are incapacitated by age, or by weakness of mind,” was “not incompatible with the principle of the independence and the equality of all human creatures.” The Italian version of the civilizing mission concealed what all imperial civilizing missions obscured — the violence of conquest, the ferocity of resistance, and the quotidian brutality of colonialism. Somalis became fodder for Italian imperial ambitions — some were conscripted to fight on the front lines of Italy’s violent campaigns in Libya and Ethiopia, while others were forced to work on Italian-owned cotton and sugar plantations in a system not far removed from slavery. What were Somalis meant to appreciate about this brutal form of tutelage?

Mancini could not have imagined that, decades later, the same logic would be used to justify the concept of “trusteeship,” introduced after the Second World War as a legal means for countries to act as guardians over non-self-governing territories. According to the U.N. Charter, trusteeship was designed “to promote the political, economic, social, and educational advancement of the inhabitants of the trust territories, and their progressive development towards self-government.” Italy, shunned by the international community after the defeat of Mussolini’s fascist government, did not become a U.N. member state until 1955, but it was allowed to assume trusteeship over southern Somalia as a condition of Somali independence down the road. The new role offered Italy a way to rebuild its standing as a good Western ally while also defending its sphere of influence in the Horn of Africa. As trustee, Italy was charged with helping Somalis build an independent state — to create legal and political institutions, develop the economy, and mold a governing class that could later take power. The ideology behind such a system was that governance needed to be taught before it could be practiced.

At the time, there was vigorous debate about whether or not to buy into this ideology of paternalism. After the Second World War, anticolonial and liberation movements flourished around the globe, and local struggles inspired and energized others across borders. Abdullahi Issa, head of the Somali Youth League (SYL) and one of the country’s most prominent nationalist leaders, was supported by Roy Wilkins and other members of the NAACP. The organization helped him launch, among other efforts, a radio and print campaign in the U.S. and in Somalia to advocate against Italy’s return. Drawing on his personal experience of living under Italian rule, Issa and his allies put forth a fierce critique of colonial domination. At the time, Somali nationalists envisioned a Greater Somalia formed of French Somaliland (modern Djibouti), British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland, Western Somalia (the eastern part of Ethiopia), and the Northern Frontier District of British Kenya (the North Eastern Province of Kenya). The radical plan to reunite Somalis who had been divided by imperial borders would have required the French and British to relinquish control over the Horn of Africa, something that neither nation was willing to accept.

The SYL did not have a monopoly on Somali political opinion. Other political parties appealed to communities that were more suspicious of unification. These groups were aware, as historian Mohamed Haji Mukhtar has explained, of the “important economic, cultural, and linguistic differences between the southern population and the predominantly nomadic Somalis of the north.” Some, like the communities from the fertile south, the country’s breadbasket, were rightfully concerned that a centralized state would impinge on their land rights. They had already borne the brunt of colonial cruelty, as their land and labor were expropriated under Italian rule. Ironically, by the late 1940s, these communities had come to believe that an Italian trusteeship would best protect their interests against the nationalists.

While the pro-Italian coalition differed with the SYL on many issues, both sides agreed on one position: Somalia was not yet prepared for independence. Even the advocates of Greater Somalia hoped for a ten-year four-power trusteeship, and the pro-Italian parties, in a 1948 declaration, contended that the Somalis needed Italy, a “sincere and disinterested” European nation, to “guide” their nascent country toward “maturity” and “to enter among the truly civilised peoples.” Of course, a Western legal framework was used to define what could be considered a legitimate, “civilised” state. Measured against that yardstick, Somalis looked at their own society and found it lacking.

The enduring Italian presence reinforced that sense of unpreparedness, constraining the horizon of political possibility. Before the trusteeship, the SYL had mobilized thousands of Somalis around an anticolonial, anti-Italian program; by the mid-1950s, the SYL leadership was actively working with Italian administrators in hopes of positioning itself to take charge of the country after independence. Issa, who had once told the United Nations that his people “preferred death to the return of Italian rule,” changed his tune once in power. Appointed prime minister in 1956, Issa went on to commend Italy for returning “to the noble tradition of the Risorgimento, a tradition rooted in the Brotherhood of man and in the support of oppressed peoples struggling to gain their independence.” Party leaders who continued to agitate against Italian rule were expelled.

The nominal purpose of trusteeship over Somalia was to develop the country’s readiness for democratic self-rule, but in 1960, Italy’s self-interested motivations became clear. When Somalia gained independence that year and flirted with the possibility of joining the British Commonwealth, the Italian minister of foreign affairs threatened to withdraw crucial financial and technical support. As Mohamed Aden Sheikh, who was then studying in Rome and would later become a Somali cabinet member, wrote, “What pains us is this brutal way by which Italy would like to put us in conditions of political vassalage.” He continued, “Italy claims to want to see us as truly independent… [but] spares no effort to place conditions and limits on this independence.”

On July 1, 1960, the Somali Republic was formed by a union of the former British Somaliland and Somalia Italiana — a step toward the Greater Somalia dreamed up by nationalists decades earlier — but the new nation kept the Italian colonial capital at Mogadishu. Even after independence, the city’s landmarks were Italian: Hotel Croce del Sud, Bar Nazionale, the Giacomo de Martino hospital, and the Cattedrale di Mogadiscio. The first national parliament building was originally constructed by the colonial government in 1938 as the Casa del Fascio, the headquarters of the Fascist Party. As Somali writer Shirin Ramzanali Fazel put it, Mogadiscio resembled “an Italian provincial town.”

As trustee, Italy had a duty to ensure that Somalis were trained to take power. During the preceding fascist era, the state had been repressive in its educational policy for its colonized subjects — “natives” didn’t need to know more than what was sufficient to serve as domestic servants (boys and boyesse), soldiers, interpreters, and clerks. Somalis could attend missionary-run and racially segregated elementary schools only up to the fourth grade, and even this minimal education was largely limited to the children of capi stipendiati (“chiefs” employed by the state) and those who served in the colonial administration or army. Just a few hundred children were enrolled in these schools each year, nowhere near the numbers needed to establish an educated governing class.

In addition to fulfilling the U.N. mandate, the institution of a new system of public education, built on Italian national curricula, also became a means of creating a new Italophone elite that would sustain Italian influence for decades. This generation of cosmopolitan Somalis studied Dante and Machiavelli in school, drank cappuccinos, drove Fiat 500 cars and Vespa motorbikes, and could speak perfect Italian, some without ever having left Mogadishu. (Other children were sent to study in Rome and Milan on scholarships from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.) They considered themselves ilbax, the Somali word for a modern, urbane sensibility, with an outward orientation toward both East and West. One of the most important things that differentiated these Mogadisciani from the people they regarded as unsophisticated recent arrivals from the hinterlands — the reer baadiyo — was their cultural fluency in Italian.

My father is a Mogadisciano of this generation. Born during the first few years of Italian trusteeship in Somalia, he came of age at a time when Italy remained central in Somalia’s cultural and political landscape. On the eve of the country’s independence, he was a boarding student at a private elementary school run by Italian Franciscan priests. When his aunt dropped him off at the school, his name was replaced with a number: he went by “37.” From then on, his young life was defined by rigor and discipline. He was woken up, like the other twenty students with whom he shared a room, by a bell. A timetable governed his hours of study, play, and work. During mealtimes, he was required to stand before his plate until a priest arrived at the head of the communal table. The father would announce, “Buon appetito!” and the boys would respond in unison, “Grazie!”

These rituals were intended, as one contemporary European commentator suggested, to be a “massive injection of modern civilization, which differs so much from the way of life of Africans.” To be independent was to be civilized — which is to say, Italianized.

“It is no accident that we are heirs to the linguistic hegemony of those who were or are at the helm of empires,” noted the Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah in 1995. “Nor do these tongues cease to occupy a central position in the lives of those who speak them even after the total disintegration of the empire.” Language was a fundamental part of the lore of Somali nationalism. At the time of independence, the language that united much of the Somali population across imperial borders had never had an official, standardized writing system. Without an orthography, it could not be the language of a state. Some proposed using the Arabic script; when rumors emerged that a scientific committee of Somali language experts had recommended the Latin script as the pragmatic choice, there were riots in the streets. Ultimately, the first two democratically elected Somali administrations were too weak to impose the committee’s recommendation and continued to conduct government affairs in Italian and English.

It took revolutionary change in the form of a military coup in 1969 to resolve the language issue. The soldiers who took over styled themselves as the Somali Supreme Revolutionary Council and adopted scientific socialism as the national ideology. In their ten-point program, which was announced on the radio after their takeover, adopting a Latin script for the Somali language was number five. Three years later, the change became official. Soon thereafter, the state nationalized education, closing foreign-language schools and requiring all students to study in Somali, using freshly printed textbooks, dictionaries, and grammar books in the new orthography. The official government bulletin and newspaper were now printed in Somali instead of Italian. And, in the biggest undertaking of all, the state conducted a mass literacy campaign that sent thousands of young Somali students and their teachers to villages and nomadic communities to spread the new alphabet.

In spite of this linguistic revolution, Italy’s cultural grip on Somalia still did not loosen. Amid strong popular and political pressure to institute higher learning in Somali or even English, the country’s first university was cofounded by the Italians. Italy paid for its construction and each year sent top Italian scholars to teach Somali students. By the mid-1980s, Italian was the medium of instruction for nine of the twelve faculties at the university. Students who had never formally studied in Italian were required to learn the language for a few weeks before beginning their degree program. In 1988, on the Italian travel writer Giuseppe Ghisellini’s first day in Mogadishu, he walked into a store and asked if anyone spoke Italian. An old Somali man responded, “You do not know Mogadiscio: here, everyone speaks Italian.”

The revolutionary government, despite its pronouncements about breaking the shackles of imperialist economic underdevelopment, had never really sought to cut ties with the former colonizer. At the same time, it cozied up to other, more important Cold War powers. It was aligned with the Soviet Union until Moscow sided with Ethiopia in a war that began in 1977, at which point Somalia became an American ally. Embittered, and propped up by U.S. military and economic aid, Somalia’s dictator Mohamed Siad Barre began cracking down on political enemies, real and imagined, and concentrated the state’s power in the hands of his family and kinsmen. Military conscriptions, corruption, and extrajudicial killings became the norm throughout the 1980s. Barre’s decision to bomb two northern Somali cities, on the pretext of fighting an opposition group, was the final straw for the American Congress. The U.S. withdrew economic and military aid in 1988, but by then it was already too late. The civil war had begun.

As the fighting raged on, ultimately leading to the state’s collapse in 1991, some outside observers placed blame on Somalis for failing to learn how to govern themselves. The civil war, like decolonization before it, became the justification for both traditional and novel interventions by Western powers. In the early 1990s, international commentators even proposed renewing the trusteeship system in Somalia. “Recolonization might be a fear among some new nations,” wrote Robert I. Rotberg, then president of the World Peace Foundation and later a faculty member at Harvard’s Kennedy School, “but countries like Somalia reached such an anarchic nadir that the Americans had no choice but to intervene on behalf of the new, unipolar world order. Likewise, the U.N. now has little choice but to govern Somalia until it can govern itself.” In 1992, a U.N. coalition, composed of soldiers from dozens of countries and led by the U.S., entered the country, ostensibly to monitor a ceasefire and protect the distribution of humanitarian aid, but its mission grew to encompass the establishment of a new Somali state. In a failure that anticipated quixotic American state-building efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, no real progress was made, and peacekeeping forces were eventually withdrawn in 1995. The years since have been characterized by intermittent foreign military interference, drone warfare, counterterrorism campaigns, and endless peace and reconstruction processes. As a laboratory for testing methods of control, surveillance, and intervention, Somalia has become part of what anthropologist Catherine Besteman has called “the new security empire.”

The current Somali federal government is secured by African Union troops and directed by foreign aid. Political elites, chauffeured around the capital in bulletproof Land Cruisers, make a show of their power, but faced with punishing sanctions, about five billion dollars of debt to international financial institutions, and relentless scrutiny in the American-led War on Terror, actual autonomy seems impossible from the vantage point of Mogadishu. Al-Shabab, the Al Qaeda-affiliated insurgent group that rules large areas of southern Somalia, continues to pose an existential threat to the federal government, which relies on the U.S., Turkey, and the European Union for billions of dollars’ worth of military training, drone strikes, intelligence operations, and logistical support. The management of public assets like the capital city’s port and international airport have been contracted out to foreign companies close to the Turkish state. Much of civil society, too, from women’s rights organizations to the press to think tanks, is sustained by outside donors.

Compared with the U.S., Turkey, and the Gulf states, Italy is currently a minor player in Somalia, but there’s reason to believe that’s changing. Italy reopened its embassy in Mogadishu in 2014, and, over the past decade, its aid to Somalia has doubled. In 2020, the two countries signed a memorandum of cooperation. Italy helped finance the administration of Somali elections in 2012 and 2016, and commands the E.U. mission to train Somali armed forces, contributing the most troops. The former Somali president Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed (“Farmaajo”) publicly acknowledged his country’s “historic” ties to its erstwhile colonizer, and even sent twenty doctors to Italy while the country was in crisis during the first weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic. Last year, Italy’s foreign minister visited the newly elected Somali president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, and Italians now help train Somali police and military officers. In partnership with professors from the prestigious Politecnico di Milano, the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation is working to reconstruct the Somali National University, which was founded during the era of Italian trusteeship and closed during the war. Somali university lecturers have been sponsored to further their education at Italian universities for the past few years.

The new initiative to bring Italophone culture back to Somalia is spearheaded by an organization called the Med-Or Foundation. Med-Or (which stands for Mediterranean-Orient) is the cultural arm of Italy’s premier defense company, Leonardo, which is itself partially owned by the Italian Ministry of Finance. The foundation was established in 2021, under the leadership of Marco Minniti, the former minister of the interior who has been called “the kingmaker of Italian politics in the field of intelligence.” That same year, Med-Or signed a memorandum of understanding with the Somali government to promote the Italian language through training courses and scholarships for Somali students to study in Italy. On January 1, 2022, the Somali national radio began broadcasting half an hour of Italian programming every day — a move that’s all the more striking considering how few Somalis still understand Italian. As Somali analyst Abdinor Dahir noted when the program was announced, “The old generation who spoke Italian have passed away or have left the country, so broadcasting a language not followed on the ground is a waste of resources.”

But Med-Or’s initiatives aren’t about meeting Somalis’ needs or catering to their interests. The Italian ambassador to Somalia, Alberto Vecchi, said the radio program was part of a larger, more complex project aimed at bolstering security across the wider Mediterranean, and Minniti has described Med-Or’s goal as encouraging “dialogue with those international players for whom Italy is a natural interlocutor.” The organization, he said, is working to establish similar “partnerships” elsewhere, in the hopes of building a network reaching throughout Africa and the Middle East. Using Med-Or to foster relationships with governments in these regions, Leonardo is growing fast, recording billions of dollars in sales to foreign governments each year.

Somalia has a special role in this calculus. Minniti regards Somalia as “a key partner for us in the Horn of Africa” and the language program itself as a way to “consolidate cooperation and bilateral relations” that is “in line with Italy’s engagement in Somalia.” In 2021, Med-Or published a think piece headlined “Why We Need Somalia,” which argued that “Europe and Italy must realize that unless Somalia is saved, the entire Horn of Africa will be lost.” The unspoken concern, beyond Al Shabab, is Somalia’s strategic position with regard to Europe’s so-called “migrant crisis.” Without Somalia, the author argues, Europe loses “a barrier to a series of potential crises that would affect also Europe and its partners.” Minniti helped oversee Italy’s now-infamous approach to migrants, limiting search-and-rescue operations, threatening to refuse to allow humanitarian boats to dock, and even charging captains of those boats with human trafficking. In Libya, Minniti deployed naval forces and partnered with the national coast guard to block asylum seekers from leaving the African continent. Called the “Minister of Fear,” Minniti and his policies were applauded by the Italian right. Though he has moved from the government to Med-Or, we can expect Minniti to continue pursuing a similar agenda — even through cultural exchange and capacity-building programs, no matter how harmless they may appear.

In his classic 1965 treatise, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah described the economic dependence that maintained colonial relations after formal European rule ended. Nkrumah exposed how, as political scientist Adom Getachew has recently written, “actions that appeared to be free legislative decisions of an independent state were in fact the result of dependence on other states, private actors, or international organizations.” A month after his book’s publication, while Nkrumah was still in office, the United States responded by withholding $100 million of food aid to Ghana. As Nkrumah had presciently observed, “Imperialism simply switches tactics.”

Capacity-building has become one of those new “tactics,” to borrow Nkrumah’s phrase. Political philosophers Silvia Federici and George Caffentzis have argued that these neoliberal programs are aimed at training African political and economic elites “to accept the diminished role Africa is to play in the global economy” — and to see their material and security interests as allied with those of the Global North. As Minniti said in his unapologetic explanation of Med-Or’s initiatives, “Almost all industrialized countries use this type of tool to underpin their relations.” He added, “The results are often very appreciable.”

In the 1940s, Somalis could look to left internationalists, pan-Africanists, and other countries in the emerging Third World for support, drawing on a robust critical vocabulary and infrastructure of anticolonialism. During that fruitful period, although they continued to be influenced by Italian culture and politico-economic dependence, many Somalis were contending with what it would mean to be independent. The recent memory of Italian domination motivated them to actively struggle with that colonial past in a way contemporary Somalis cannot.

For the many Somalis currently grappling with the worst drought in four decades, as well as the predations of Al Shabab and state authorities, organizing protests that reflect popular discontent might seem like a luxury, if not a danger. Anti-imperialism and left internationalism are no longer the powerful movements they once were. Many of the revolutions in the Global South, especially since the Occupy Movements and Arab Spring of 2011, have been crushed. There are some beacons of hope, such as the Black Alliance for Peace’s campaign to end AFRICOM, the U.S. military command in Africa, but without more of them, the status quo is unlikely to change. While it may seem like a distraction from these myriad challenges, the Italian language program is far from trivial: it’s a visible trace of how colonialism persists and takes on new forms in Somalia. In naming the programs as the propaganda that they are, Somalis are exercising their right to refuse tutelage.

Today, some Somalis may flirt with Italophilia, reminiscing about the bygone days of stability and high Italian culture. But Med-Or’s initiatives remind us that there’s a different tradition we could revive instead. On April 14, 1960, Yusuf Osman Samantar, a political leader who was later imprisoned under the Barre regime, delivered a lecture titled “Neo-Imperialism in Africa.” He advised Somalis to take stock of their history of oppression and exploitation by foreign powers if they wanted to build a truly free society. Ironically, the lecture was given, and later published, in Italian, and is among the many historical sources that are inaccessible to most Somalis. Perhaps the new Italian courses at the national university will create an opportunity for more young people to reconnect with — and learn from — their predecessors’ serious, public debates about independence, which may be hard to remember after decades of dictatorship and political crisis. But that’s probably not the sort of capacity Italy is looking to build with the return of Italian in Somalia.

Iman Mohamed is a Somali writer and doctoral candidate in history at Harvard University. She is based in Rome.